Outside intervention explodes in Libya

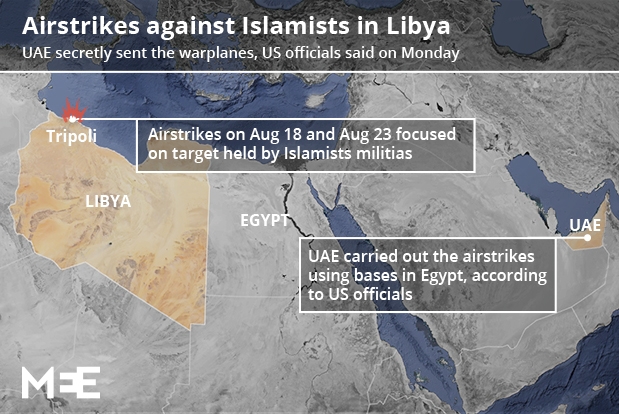

Nato presents itself as an “honest broker” in Libya’s brutal civil war, but there was nothing honest about it refusing to go public on what it knew about the two sets of air strikes reportedly launched from Egyptian bases against Islamist militias in Libya last week.

Nato monitors Libyan airspace as part of its ongoing duties devolved from the UN security council, following resolutions passed in 2011 to enforce an arms embargo.

American AWACs planes keep watch on Libya’s air space and would have seen not just the strikes, but the arrival of UAE jets, a refuelling tanker and support planes in Egyptian bases prior to the strike. Point being, it would have seen what was going on.

The New York Times is a paper of record, its reporters insist they obtained the information about Emirati and Egyptian involvement from separate military sources, and the bombing claims fit the facts on the ground.

Those facts began late on Sunday night, 17 August with the sound of jets high in the sky over Tripoli, a city that was into its fifth week of punishing rocket and artillery bombardments between militias from the towns of Misrata and Zintan that has reduced some districts to rubble.

Without warning, bright flashes lit the sky, images on one brave Libyan’s cellphone showing the eruption of red flame as bombs scored a direct hit on a Misratan ammunition depot.

More than 20 sites were struck that night, both in Tripoli and far south of Misrata where Libya Dawn forces keep rockets in hardened shelters near Waddan. Then the jets vanished.

Six days later they were back; again, at night, and this time circling for an hour before ordinance again rained down on 22 August, a Friday night. As with the raids over the night of 17 August, the strikes were precise, hitting more Misratan ammunition depots, barracks and the interior ministry, hours after Misratan units had stormed the building. Among the 17 dead were two sons of a Misratan commander.

Air strikes in Libya are nothing new: since May former general Khalifa Haftar has had the use of two Russian-made air force jets and an attack helicopter to pound Islamist bases in Benghazi.

But Benghazi is 400 miles to the east, and Libya has no night-bombing capabilities, nor any means of refuelling the jets, leading to speculation the bombing was foreign.

The Islamist Libya Dawn movement, an alliance of Misrata and Islamist militias, seem to have been proved right, claiming on Saturday that the UAE and Egypt were behind the attacks, and vowing revenge. A US-made Mark 82 bomb was recovered from the wreckage, with Libya’s government, having fled Islamist forces in Tripoli for the east of the country, voicing suspicions foreign jets were responsible. Libya’s authorities may themselves want to know why, if it was true, US officials told the New York Times before they told a supposed ally.

That threat of revenge has further ramped up tensions in the region, with neighbouring states fearing that militants will use airliners at Tripoli and Misrata airports under Dawn control for suicide attacks. Egypt and Tunisia have warned Libyan craft to stay away, while Algeria has deployed missile batteries on its border. The United States has jets deployed in Italy and ships in the Mediterranean which can shoot down any straying aircraft.But the salient feature of the air strikes is that they failed: Hours after the second round of bombing, Misratan units surged into Tripoli International Airport, which they had been bombarding for the past month, as pro-government defenders, a militia from Zintan, withdrew. For good measure, the Misratans then set the airport ablaze before pulling back to consolidate their hold of Tripoli.

Foreign intervention

History is littered with examples of secret and poorly conceived foreign intervention: think Vietnam, or the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, or for that matter US operations in Afghanistan and its invasion of Iraq. The problem with all such interventions, large and small, is that they change the game in unpredictable ways.

In the case of Libya’s bombing, it reinforces the suspicion that the country’s worsening civil war is now the plaything of a struggle between two Gulf states, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

Qatar backed Libya’s Islamists from the first days of its 2011 revolution, creating the Islamist 17 February brigade which is now battling UAE-backed government forces in Benghazi and shipping anti-tank missiles that allowed Misrata to win its battle against the forces of Muammar Gaddafi. Doha provided jets for Nato’s 2011 bombing intervention that gave victory to Libya’s rebels who are now fighting each other.

Qatar’s links with Islamist militias remain strong: Ismail Salabi, commander of an Islamist militia in Benghazi, is the younger brother of Ali Salabi, a key Libyan politician and religious guide based in Qatar. In the aftermath of the revolution, Al Jazeera gave a platform to Salabi, until Washington asked Qatar to tone down his Islamist rhetoric, fearing exactly the Islamist-nationalist split that is now tearing the county apart.

Abdul Hakim Belhaj, a former revolutionary fighter, is another friend of Qatar, with wags in Tripoli noting that the posters for his candidacy in 2012 elections were produced in the emirate’s maroon and white colours.

The UAE’s role in Libya has been equally key. Mahmoud Jibril, leader of Libya’s nationalist National Forces Alliance, a former economic advisor to Gaddafi and the revolution’s first prime minister, lives in self-imposed exile in the Emirates.

But attempts by both Gulf states to influence Libya’s chaotic politics have often run into the buffers. The UAE provided red and white police jeeps to favoured militias in the revolution’s aftermath, but left the phone number of the Dubai complaints office stamped on their sides.

And when Tripoli’s leading Islamist formation, the Libyan Revolutionary Operations Room, stormed the city centre Corinthia Hotel to kidnap prime minister Ali Zaidan last October, its fighters found time to assault Qatari diplomats. The Qataris lived on several floors in the hotel, and some were pistol whipped, despite protesting that they were essentially on the same side.

Western attempts to meddle or mediate have been similarly ineffective: Britain, Italy, France and the United States all competed to sell Libya defence equipment over the past three years, despite their duties to enforce a UN arms embargo. The US secured the biggest order, for more than 200 Humvee personnel carriers, but recent fighting has seen many end up in the hands of Islamist militias, an echo of the situation in Iraq.

Libyans themselves, having spent most of their history dominated by Turkish, Italian and British occupiers, are resistant to foreign meddling, from whatever source. After the 2011 revolution, Qatari flags were for sale on the streets of Tripoli and Benghazi. Now they are being burned by nationalists, along with effigies of the emir.

But the bombing may change everything, not least because it will invite Qatar to find a means of responding. The success of the Islamist Libya Dawn movement in seizing Tripoli and Misrata and declaring its own government has left the country split between Islamists and nationalists. The temptation of the Gulf states, and anyone else eyeing Libya’s rich oil bounty, to meddle is sharper than ever.

In the latest of a series of joint statements, the United States, Italy, France and Great Britain have urged both sides to stop fighting and start talking, offering themselves as impartial mediators. They would give their credibility a big push by now coming clean about what they know about the air strikes, and whether more are on the way.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.