Lalish: Ancient Yazidi spiritual site in Iraq where locals enjoy peace

LALISH, Iraqi Kurdistan - Young people take pictures of themselves on their phones while others sit around enjoying a picnic. This happy and peaceful scene on a summer day takes place in the spiritual heartland of northern Iraq's Yazidi community in mountainous Lalish.

Middle East Eye recently visited Lalish in Nineveh governorate, Iraqi Kurdistan. Here, 50km north of Mosul, lies the mausoleum of Sheikh Adi bin Musafir, the 12th-century founder of Yazidism.

The spiritual centre looks today more like a quiet, stony village set amid the hills, accessible by only one road. Entering the shrine, visitors have to remove their shoes. The buildings, many of which are hundreds of years old, are surrounded by trees.

On a Friday, the entire area of the sanctuary was full of people who had come there for a weekend trip. Most came from al-Shikhan, a small town located several kilometres from Lalish.

This is the oldest and most significant sanctuary of what was originally a Sufi order known as the Adawiyya, Birgul Acikyildiz-Sengul, researcher at Paul-Valéry Montpellier University, France, explains in her thesis on Lalish.

“They are commonly known as the people of the peacock angel or the worshippers of Satan because of their respect for the peacock angel (Tawuse Melek). In Yazidi dogma, God delegated his powers to seven angels, 'seven mysteries'. The peacock angel, the most powerful of the seven, is the sole representative of God on earth.”

A young man from Lalish explained how one is supposed to behave in the sanctuary and guided us through the temple. Every year guardianship of the sanctuary is given over to different families.

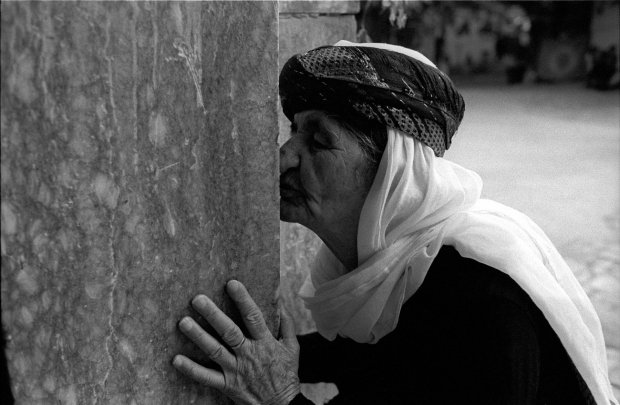

The guide showed us the huge vases where olive oil is stored to be used during religious rituals and celebrations. In the main part of the temple pilgrims kissed the pillars and made knots on colourful cloths in order to make wishes.

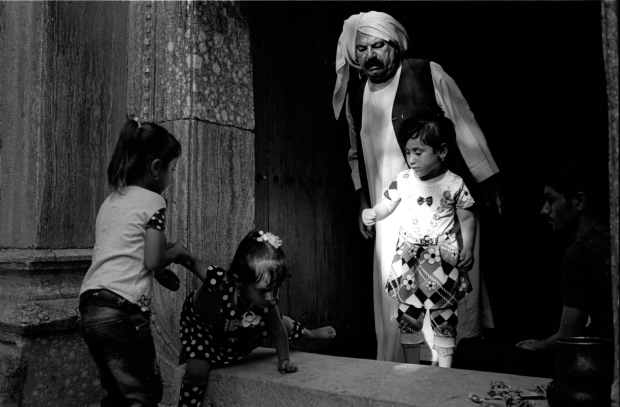

It is prohibited to step on the threshold on the doorways throughout the temple, something visitors must remember as they walk around the sanctuary.

A young man and his wife and children were sitting under a tree, finished eating and invited us to join them. The whole place has a unique and spiritual atmosphere.

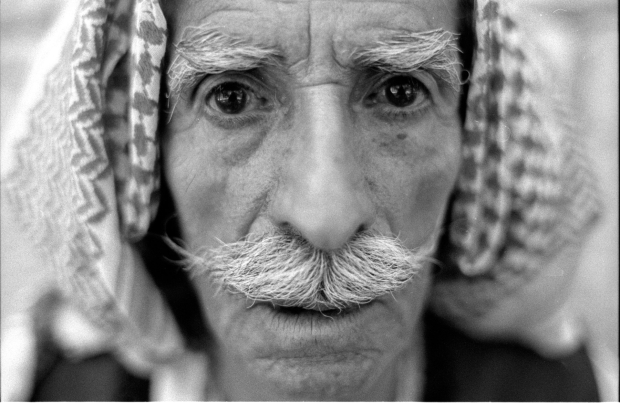

Yazidis are reluctant to speak about their religion and customs to strangers. A man who was our guide invited us in the evening to join him as families started small fires in 365 special stoves located around the temple complex. This ritual happens once a year using small twigs soaked in olive oil from the temple, he explained.

In the evening, Middle East Eye came back to photograph the ceremony of lighting the olive twig knots, after which family members cleaned up the main square opposite the temple in a sublime moment for all those present.

This idyllic atmosphere is something of a surprise for a visitor, considering the fact that Yazidis in 2014 suffered a 21st century genocide at the hands of Islamic State (IS) group militants; and only 50km away in Mosul, the most intensive urban fighting since World War Two ended just weeks ago.

Here in Lalish, there is no threat or sense of danger or tension. Kurdish police and army protect the main gates while keeping a low profile on the site.

Clearly, despite the reports of IS brutality and war that we see coming from this area, it is important to note that there are normal people continuing their lives peacefully and maintaining traditional religious practices carried on over generations.

There are many myths about Yazidism and its customs, some made infamous in IS propaganda, such as they are followers of Satan. Most of those stories are a result of a lack of knowledge about their religion.

Yazidis are ethnically Kurds, but many of them describe themselves as Yazidi without any national or ethnic association. They speak the Northern Kurdish language in the Kurmanji dialect, locally known as Badini. It is also the Yazidi ceremonial language and the dominant tongue heard in Lalish, although a few of the pilgrims spoke in Arabic too.

Yazidis have experienced many years of persecution, especially recently at the hands of Islamic State group. This includes the massacre of Yazidis by IS in 2007 in northern Mosul and al-Qahtaniya near Sinjar. Al-Qathaniya was the second-most deadly attack in the 21st century after the World Trade Center attacks, killing 500 people and wounding 1500. Then in 2014, thousands of Yazidis were massacred by IS and more than 5,000 women were sold into slavery.

But today, in Iraqi Kurdistan, the Yazidis are safe, watched over by Kurdish Peshmerga on the main gate of the shrine.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.