Kurdistan 'healing garden' aims to help Iraqis deal with trauma

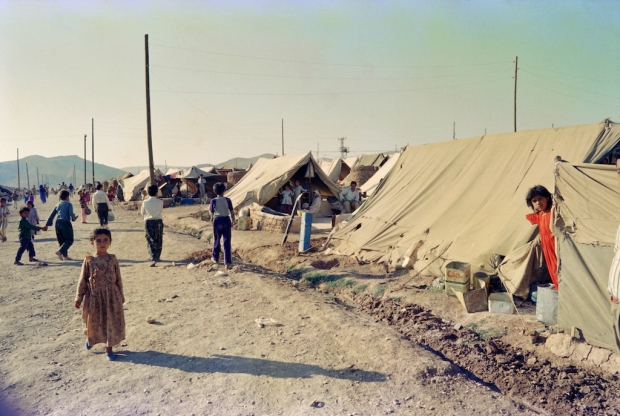

CHAMCHAMAL, Iraq - A small patch of land just off the Chamchamal Road, around 50 kilometres east of Kirkuk, might seem unassuming to most, but to the residents of the suburb of Shoresh it marks the latest attempt to help them deal with a generation of pent-up trauma and psychological abuse.

The facility is a "healing garden," the latest project by the Jiyan Foundation for Human Rights aimed at helping survivors of intense grief and trauma come to terms with their experiences through animal-assisted therapy. Locals are invited to interact with an array of goats, chickens, horses, rabbits and other animals kept in the garden.

“If you look around you see that almost all the families own two or three sheep, goats or cows, so they have good contact with their animals. Because it’s from their background," explained Ako Mohammed, manager of the Chamchamal Jiyan Foundation branch.

The Anfal campaign - genocide

Shoresh is almost entirely made up of Kurds who fled Saddam Hussein's brutal Anfal campaign in the 1980s. Up to 180,000 Kurds were slaughtered as punishment for rebelling against the Baathist government.

The most notorious incident of the campaign was the chemical weapons attack on the city of Halabja which saw more than 5,000 people killed. The campaign has since been characterised as genocide by a number of foreign governments and human rights groups.

According to Human Rights Watch, 90 percent of the villages targeted by Saddam's campaign were destroyed, forcing residents to flee into the larger cities.

“Those people who have been subjected to trauma, they automatically and unconsciously try to get close to the animals to feel comfortable," explained Mohammed.

“We started discussing this with the general manager and it was his idea to set up a healing garden like this, mainly using animals from the area," he added.

My father died in the Anfal campaign, my paternal uncle, and another uncle

- Gorran, therapist

"My father died in the Anfal campaign, my paternal uncle, and another uncle," said Gorran, one of the therapists at the centre. "Right after the Anfal campaign destroyed our villages we had nowhere to live, so we moved into Shoresh."

Gorran's family fled to the neighbourhood of Qader Karam in Shoresh, which was named after their village. Until 2003, the village - only one hour away from Shoresh - was empty of civilians and only military officials remained in control of the areas, he said. All the civilian houses were "flattened to the ground". What was left was covered in minefields.

The consequences of trauma

Gorran currently deals with a large number of children with a variety of problems associated with trauma, such as behavioural and speech disorders. The healing garden, he said, works in addition to his direct therapeutic work and helps create a more floral and flourishing environment in the otherwise fairly barren terrain of Chamchamal.

"This is a perfect project. You have seen that we have some birds and animals from the area, but we also have some animals that are not seen here [because] we are far away from the forest. So people here have a chance to see new birds that they have just seen on TV, and also there will be lots of plants here. It will be like a forest for them - we do not have forests in Chamchamal," he said.

The Jiyan Foundation for Human Rights was first formed in the restive city of Kirkuk in 2005, where it established a centre for dealing with victims of torture. It soon expanded to include centres across the Kurdistan region, in the cities of Duhok, Erbil and Sulaymaniyah.

I am 31 years old and I have never seen a horse so close as I have seen here

- Gorran, therapist

Its work has grown exponentially since 2005 as Iraq descended into chaos and atrocities occurred at the hands of the US-led occupation forces, sectarian militias and, most recently, the Islamic State group.

Funding for the foundation has poured in from the European Commission, the German foreign office, the Lutheran World Federation, as well as the Kurdistan Regional Government.

Modern meets traditional

Working with the German sustainable architecture firm Ziegert Roswag Seiler Architekten Ingenieure, the centre began constructing mud huts in March 2016, based on the style originally used by residents of the emptied villages, but combined with modern environmental techniques that prevent the huts from being damaged in the sun.

"[Ziegert Roswag Seiler Architekten Ingenieure] went to the villages and saw how the houses are built and they used the cultural design of the houses and added technology so the houses would last for a long time," said Mohammed.

It reminds them of their childhood

- Ako Mohammed, manager of the Chamchamal Jiyan Foundation branch

Locals, particularly former village elders, also provided input into their construction. The mud, sand and wooden materials used to build the huts eventually decompose and biodegrade naturally.

The huts work as therapy rooms for the patients to work through their trauma. One technique used, primarily with children, is "mud therapy" in which they are encouraged to play with mud, get dirty and interact with the animals, before coming back to the huts for a discussion.

"We already had clients and local people coming here," explained Mohammed. "They feel more and more comfortable seeing these houses because they grew up in the villages where they stayed in houses like this and now they live in concrete houses. It reminds them of their childhood."

In order to water the garden, the centre redirected an unused public sewage canal to feed into the plants.

The canal runs underneath the garden and carries household greywater from the nearby homes through a decentralised water processing system set to clean 100 cubic metres of dirty water each day.

A system built underground processes human and animal waste into bio-gas which is used as heating for the buildings.

There are also plans to bring bees to the garden to produce honey which would be sold at cheap prices, with the money reinvested in the healing garden. Another plan is to install a series of solar panels.

Eventually what started off as just nine buildings is set to expand into a complex providing a new vision for environmental sustainability in a country still heavily dependent on oil.

One of the engineers said he hoped that the garden could eventually be totally self-sustaining.

“We want the government and other groups to see our projects, like the bio-gas system, like the water treatment system and see that it is very simple but very useful for people’s lives, and for the country and for the environment," said Mohammed.

We want the government and other groups to see our projects, like the biogas system, like the water treatment system and see that it is very simple but very useful for people’s lives

- Ako Mohammed, manager of the Chamchamal Jiyan Foundation branch

Mental health support

Iraqis have suffered decades of trauma as a result of war, sectarian conflict, poverty and displacement. Mental health professionals have warned that the challenges the country faces are exacerbated by a shortage of specialists as well as the problems society has in accepting the reality of psychological problems.

“The need for mental health support is obvious when I see the number of patients and the severity of their trauma,” said Melissa Robichon, a psychologist with Doctors Without Borders in Iraq.

“However, there are many challenges, including the stigma that surrounds mental illness. Many people who would benefit from treatment will not join the programme for fear of what the community might think."

"It's a unique project for Chamchamal, even for all of Kurdistan," said Sirwan, one of the gardeners. "I hope there might be a few other projects like this."

"When people come here, they have good feelings about their past," he added.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.