Why the Balfour Declaration did not promise a Jewish state

For some time, I have been grappling with the British reasons behind the Balfour Declaration and what it really meant.

Let us start with what we know.

In early March 1915, with a sense of urgency, Czarist Russia demanded that Britain and France should enter into negotiations over various concerns of the Entente powers in the Ottoman Empire. The Russians, seeking to secure control over the Bosporus and Dardanelle straights, were prompted to act after the launching of the British Gallipoli campaign on 19 February 1915, which aimed, in its first stage, at capturing Istanbul by a naval force.

British strategic imperatives in the Middle East

Russian interests in Thrace, the Straights and Eastern Anatolia, were agreed upon by the British in the Constantinople Agreement of 12 March 1914 (to be followed by the French on 10 April 1915).1 Yet, aware that it would soon be confronted by similar French demands, the government in London decided to form an interdepartmental committee, chaired by Sir Maurice de Bunsen, to look into, and define British strategic imperatives in the Middle East.

Delineation of the British and French interests, however, had to be negotiated. These negotiations started in London, on 23 November 1915, where the British were represented by Sir Mark Sykes and the French by Francois George-Picot. The two reached an initial agreement in January 1916.

Claims by some historians that the British Zionist policy was motivated by Biblical, Protestant-Zionist affinities, are a bit farfetched

Until the conclusion of negotiations between Sykes and George-Picot in January, there is no record of any meaningful contacts between the government of British Prime Minister at the time, HH Asquith (who served from 1908 to 1916) and the Zionist movement. Any contacts existed were made on personal, non-official bases.

Although it was met with criticism in Whitehall, the government decided to ratify the draft agreement between Sykes and George-Picot on 16 May 1916; first, because it did not look politically tactful to ask for revisions when France was shouldering the heaviest burden of the war; and second, because of the failure of the Gallipoli campaign.

It should also be remembered that, by then, the British had not yet made any substantive progress, neither in their Iraqi campaign nor in the Sinai expedition.

First official contact with Zionists

It was during that crucial period between the circulation of the draft Sykes–Picot agreement and its ratification that the first British official contacts with the Zionists were initiated.2

What prompted these contacts was the allusion to the aspirations of Zionist Jews to settle in Palestine, included in the critical response to the Sykes-Picot draft agreement, written by Captain Reginald Hall, chief of Naval Intelligence, in January 1916.

A month later, Hugh O’Beirne, one of the most senior officials at the Foreign Office, distributed a minute, summing up the FO's views of the political advantages that adoption of Zionist interests in Palestine could bring to the allies’ cause, especially in the US.

Since the search had already begun for ways to release Britain from her obligations to France in the Middle East, even before the ratification of the agreement, Sykes moved to explore the Zionist option.3

From the British perspective, the area south of the line extending from northern Iraq to the Mediterranean, or from the last E of Acre to the last K of Kirkuk, as Sykes once put it, should come under British control.

While it was obvious that the agreement with the French did not convincingly fulfil such a vision, it was believed that bringing the Zionists to the table could supersede the French demands and secure southern Syria as a British area of influence.

Cynical calculations

Claims by some historians that the British Zionist policy was motivated by Biblical, Protestant-Zionist affinities, are a bit farfetched.4

The British approach to the Zionists was rather born out of cynical calculations, shaped by strategic requirements of the empire in Egypt, the Eastern Mediterranean, Iraq and India. Neither PM Asquith, foreign secretary Edward Grey, nor the two Catholics, Mark Sykes and Hugh O’Beirne, was a Zionist.

Of the two Jewish members of government at the time, Herbert Samuel and Edwin Montague, only the first had Zionist connections.

Samuel's January 1915 memorandum, in which he invited the government to take the Jewish aspirations in Palestine into consideration, did not raise much interest. The Asquith government took no action on Samuel's proposal, his memorandum was not circulated to the concerned departments, and was kept, and can still be found, in the cabinet papers.5

Moreover, De Bunsen's June 1915 report did not include any reference to Zionism or Zionist interests.6

It was evidently upon reading Hall's remarks and O’Beirne's minute that Sykes took the initiative to make his first Zionist contact. He met with Samuel and Moses Gastor in the spring of 1916, and later in the year with Aharon Aaronsen.

At the same time, during the months prior to the change of government in December 1916, both Sykes and officials at the Foreign Office exchanged various ideas for the accommodation of Zionist aspirations in Palestine, with the full knowledge of Sir Edward Grey.

Neither David Lloyd George, Asquith’s successor in Downing Street, nor Arthur Balfour, who replaced Grey at the Foreign Office, undertook any major shift of policy in the Middle East. It is true that Lloyd George was more enthusiastic about the Middle Eastern front, mainly hoping to bring some good news to the British people, dismally tired of the longevity and horrendous losses of the war.

Yet, it is also true that discussion about the withdrawal from commitments made to the French in the Middle East, as well as about Zionist interests in Palestine, had already started before the taking of office by Lloyd George's government. Above all, Sykes not only remained to serve the new government, but was also promoted to the cabinet secretariat.

'The national home'

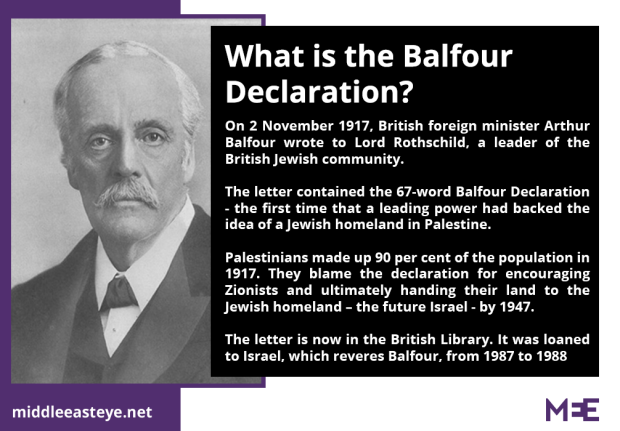

In its meeting of 31 October 1917, Lloyd George's government approved the text of the foreign secretary's declaration to the Zionists, which had already been subjected to several drafts. The 2 November 1917 declaration took the form of a letter from Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, the most eminent of the Jewish community in the UK, to be communicated to the Zionist Federation in Great Britain and Ireland. It read:

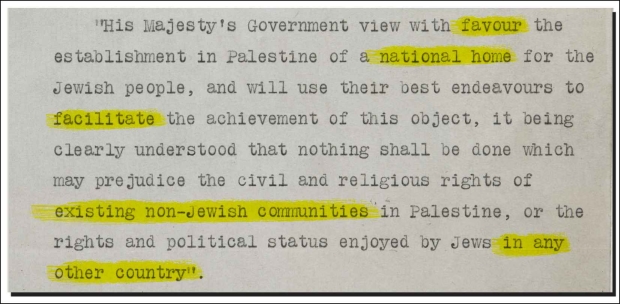

"His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."7

The term "national home" is no doubt an ambiguous one. It certainly did not mean a state; and as James Galvin has observed, it had no precedent in international law. Almost every single Zionist leader in the subsequent decades, together with British officials who came to deal with the Palestine question, was aware of the ambiguity of the term.

Even after the founding of the state of Israel, doubts were still lingering about the intent behind the "national home" expression.

In 1949, the Jewish Year Book of International Law published an article by Ernst Frankenstein, a prominent professor at The Hague Academy of International Law, entitled "The Meaning of the Term National Home for the Jewish People".8 Employing an arsenal of legal rhetoric, Frankenstein could not find any concrete shred of evidence to prove that the Balfour declaration implied the establishing of a Jewish state in Palestine.

During the British mandate period, the first clarification of the declaration was to be suggested in the July 1937 Peel Commission report, which recommended the partitioning of Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab one to be united with Trans-Jordan.9 The Peel Commission recommendations, however, did not stand for long, for in November 1938, another commission, headed by judge Woodhead, reached the conclusion that the partition plan was impractical and could not be implemented.10

Balfour-Curzon correspondence

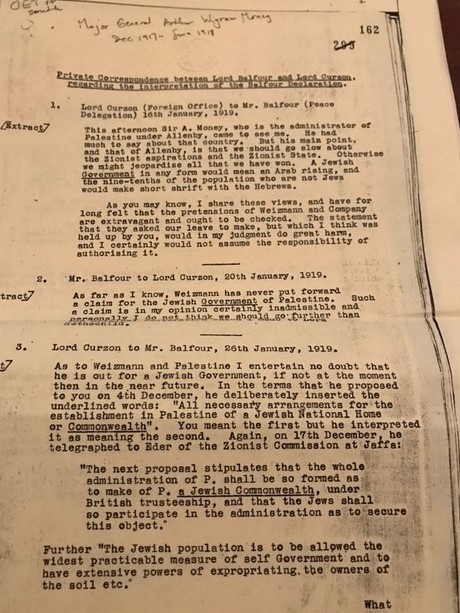

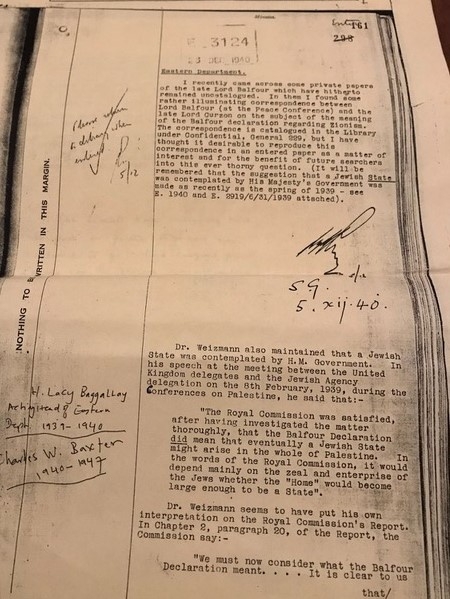

In a research visit to the Public Record Office, a few years ago, I came across a highly interesting document, enclosing some early 1919 correspondence between Lord Balfour, the foreign secretary, and his fellow member of the Cabinet, Lord President of the Council, Lord Curzon. It is perhaps worth noting that Curzon was to succeed Balfour in the Foreign Office later in the same year.

The first of Curzon's correspondence to Balfour, who was at the time in Paris for the peace conference, was written on 16 January 1919, following a meeting that Curzon held with Major General Arthur Wigram Money, Allenby's administrator of Jerusalem.

'A Jewish government in any form would mean an Arab rising, and the nine-tenth of the population who are not Jews would make a short shrift with the Hebrews'

- Lord Curzon

In his letter, Curzon said that what he understood from Money is that: "A Jewish government in any form would mean an Arab rising, and the nine-tenth of the population who are not Jews would make a short shrift with the Hebrews."

Indicating his agreement with Money's assessment, Curzon added, "As you know, I share these views, and have for long felt that the pretensions of Weizmann and Company are extravagant and out to be checked."

A few days later, on 20 January, Balfour replied. His letter was brief but unequivocal, asserting the view that the British commitment to the Zionists did not entail the establishment of a Jewish state. He wrote: "As far as I know, Weizmann has never put forward a claim for the Jewish Government of Palestine. Such a claim is in my opinion certainly inadmissible, and personally I do not think we should go further than the original declaration which I made to Lord Rothschild."

On 26 January, Curzon wrote a second, elaborate letter, in which he explained to Balfour that "… while Weizmann may say one thing to you, and while you may mean one thing by a National Home, he is out for something quite different."

No Jewish state in Palestine

With a growing sense of desperation over the Palestine policy, Curzon sent a third letter to Balfour, on 25 March 1919, commenting on the decision by the Peace Conference to send an American commission of inquiry to the Arab Middle East.

He wrote: "The one thing I should personally like the commission to do would be to extract us from the position in Palestine… I told you some time ago that Dr Weizmann had departed altogether from the modest programme upon which he agreed with you a year or more ago, and that the ambitions of the Zionists were exceeding all bounds."

Curzon concluded his correspondence by expressing the hope that the American commission, known later as the King-Crane Commission, would advise that "the mandate in Palestine should be conferred upon anyone else rather than Great Britain."

These were the opinions of two grandees of the British government during and immediately after the war. While both served as foreign secretaries, Balfour was the one whose name would forever be attached to the infamous declaration to the Zionists. Yet both were unmistakably clear that the declaration was not about the founding of a Jewish state in Palestine.

There is no doubt that the Balfour declaration was the source of all evils in the Arab Middle East. It does seem, however, that even that piece of evil was not meant to give rise to the monster it came to bring into existence.

Notes:

1 Robert J. Kerner, “Russia, the Straits, and Constantinople, 1914 – 15,” The Journal of Modern History, 1, 3 (Sep. 1929): 400 – 15; Hugh Seton-Watson, The Russian Empire, 1801 – 1917 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1967), 706 – 7. At least partially, the Gallipoli campaign was prompted by earlier Russian requests for Britain to stage a diversionary attack against the Ottomans, who launched a major offensive on the Russian front in January 1915. David Fromkin, A Peace to End All Peace (London: Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1989), 128.

2 Mayir Vereté, “The Balfour Declaration and Its Makers,” in Mayir Vereté, From Palmerston to Balfour, ed. Norman Rose (London: Frank Cass, 1992), 1 – 38, esp. 9 – 16. Vereté’s seminal article was first published in Middle Eastern Studies, 1970.

3Vereté, “The Balfour Declaration and Its Makers,” 12 – 13.

4For example, Barbra W. Tuchman, Bible and Sword: England and Palestine from the Bronze Age to Balfour (New York: New York University Press, 1956); Regina Sharif, Non-Jewish Zionism: Its Roots in Western History (London: Zed Books, 1984).

5Herbert Samuel, “The Future of Palestine,” CAB 37/ 126. The memorandum was discussed by the cabinet on 13 March 1915, where, according to Asquith, only David Lloyd George, Chancellor of Exchequer at the time, supported its proposal. See Jonathan Schneer, The Balfour Declaration: The Origins of the Arab–Israeli Conflict (London: Bloomsbury, 2011), 145.

6CAB 27/ 1, Minutes and Reports of the Committee on Asiatic Turkey, June 1915.

7The Times, 9 November 1917.

8Ernest Frankenstein, “The Meaning of the Tern ‘National Home for the Jewish People’,” The Jewish Yearbook of International Law, eds. N. Feinberg and J. Stoyanovsky (Jerusalem: Rubin Press, 1949), 27 – 41.

9Cmd. 5479: The Secretary of State for Colonies, Palestine Commission Report (The Peel Commission Report), London, July 1937, 381 – 2; Cabinet Minutes, 30 June and 5 July 1937, Cab 28/ 37.

10Cmd. 5854: Palestine Partition Commission Report (The Woodhead Commission), London, November 1938; Palestine Statement by His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom, 7 November 1938, FO 406/ 76/ E 6506.

11Private Correspondence between Lord Balfour and Lord Cuzon, Regarding the Interpretation of the Balfour Declaration, attached to FO 371/ 24565/ E 3124, 5 and 23 December 1940. The correspondence were found among Lord Balfour’s papers at the Foreign Office by an official at the Library Department, most likely its head Charles W. Baxter. Aware of the confusion surrounding British policy on Palestine, following the publication of the 1939 White Paper, officials at the Library Department distributed the correspondence for the attention of their colleagues at the Eastern Department on 5 December 1940. The correspondence, commented upon by officials at the Eastern Department, were listed in the Eastern Department records on 23 December 1940.

- Basheer Nafi is a historian of Islam and the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Palestinian mother struggles to keep her young son from being arrested by an Israeli soldier as the soldier pulls the child into the central police station, right, 4 April 1994 (Reuters)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.