INTERVIEW: Ilan Pappé: How Israel turned Palestine into the biggest prison on earth

The Six Day War of 1967 between Israel and the Arab armies resulted in the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Israel sold the story of this war as an accidental one. But new historical documents and minutes from the archives show that Israel was well prepared for it.

In 1963, figures from the Israeli military, legal and civil administrations enrolled in a course at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, to set up a comprehensive plan to deal with the territories that Israel would occupy four years later, and manage a million and half Palestinians living in them.

The motivation was the failure in how Israel dealt with the Palestinians in Gaza in its short-lived occupation during the Suez Crisis in 1956.

In May 1967, weeks before the war, Israeli military governors received boxes that contained legal and military instructions on how to control the Palestinian towns and villages. Israel would go on to transform the West Bank and Gaza Strip into mega prisons under military rule and surveillance.

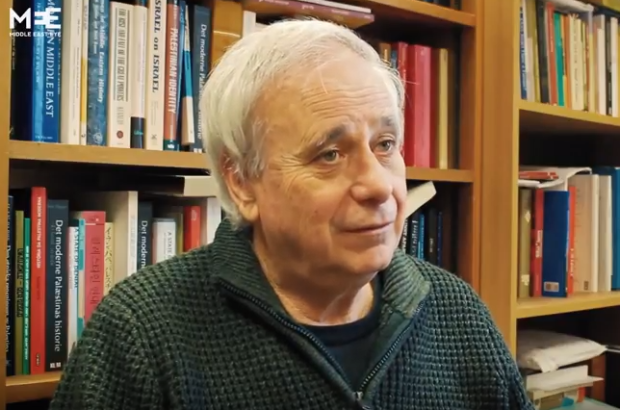

Settlements, checkpoints and collective punishment were part of this plan, as the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé shows in The Biggest Prison on Earth: A History of the Occupied Territories, an in-depth account of the Israeli occupation.

Published on the 50th anniversary of the 1967 war, the book has been shortlisted for the Palestine Book Awards 2017, organised by Middle East Monitor, due to be announced in London on 24 November. Pappé spoke to Middle East Eye about the book and what it reveals.

Middle East Eye: How does this book build on your previous book, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine about the 1948 war?

Ilan Pappé: It is definitely a continuation of my earlier book The Ethnic Cleansing that describes the events of 1948. I see the whole project of Zionism as a structure not just as one event. A structure of settler colonialism by which a movement of settlers colonises a homeland. As long as the colonisation is not complete and the indigenous population resists through a national liberation movement, each such period that I'm looking at is just a phase within the same structure.

Although The Biggest Prison is a history book, we are still within the same historical chapter. It's not over yet. So in this respect, there should be probably a third book later on looking at the events of the 21st century and how the same ideology of ethnic cleansing and dispossession is being implemented in the new era and how it is resisted by the Palestinians.

MEE: You speak about ethnic cleansing taking place in June 1967. What happened to the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip then? How was this different from the ethnic cleansing of the 1948 war?

IP: In 1948 there was a very clear plan to try and expel as many Palestinians as possible from as much of Palestine as possible. The settler colonialist project believed it had the power to create a Jewish space in Palestine that would be totally without Palestinians. It didn't really work that well but it was quite successful as you all know. Eighty percent of the Palestinians who lived within what became the state of Israel became refugees.

As I show in the book, there were some Israeli policymakers who thought maybe we can do in 1967 what we did in 1948. But the vast majority of them understood that the 1967 war was a very short war, it was for six days, and there was already television, and quite a few of the people that they wanted to expel were already refugees from 1948.

So, I think the strategy was not ethnic cleansing in the same way that it was implemented in 1948. It was what I would call incremental ethnic cleansing. In some cases they expelled droves of people from certain areas such as Jericho, the Old City of Jerusalem, and around Qalqilya. But in most cases they decided that military rule and a siege to enclose Palestinians in their own areas would be as beneficial as expelling them.

From 1967 until today, there is a very slow ethnic cleansing that probably stretches over a period of 50 years and it's so slow that sometimes it can only affect one person in one day. But if you look at the whole picture from 1967 till today, we're talking about hundreds of thousands of Palestinians that are not allowed to return to the West Bank or the Gaza Strip.

MEE: You differentiate between two military models that Israel uses: the open prison model in West Bank and the maximum security prison model in Gaza Strip. How do you define these two models? And are these military terms?

IP: I use these terms as metaphors to explain the two models that Israel offers to the Palestinians in the occupied territories. I insist on using these terms because I think the two-state solution is actually the open prison model.

The Israelis control the occupied territories directly or indirectly, and they try not to penetrate into the densely populated Palestinian towns and villages. They partitioned the Gaza Strip in 2005 and they're still partitioning the West Bank. There is a Jewish West Bank and a Palestinian West Bank which is no longer a coherent territorial area.

In Gaza the Israelis are the wardens that lock the Palestinians from the outside world but they don't interfere with what they do on the inside.

'We should talk about ethnic cleansing. We should find what replaces apartheid. And we have a good example in South Africa. The only way to replace apartheid is with a democratic system.'

The West Bank is like an open-air prison where you send petty criminals who are allowed more time to go outside and work outside. And there's no harsh regime inside but it's still a prison. Even the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, if he moves from Area B to C, he needs the Israelis to open the gate for him. And that's for me very symbolic, the fact that the president cannot move without the Israeli jailer opening the cage.

There is, of course, a Palestinian response all the time to this. Palestinians are not passive and they don't accept it. We saw the first Intifada and the second Intifada, and perhaps we will see a third Intifada. The Israelis say to the Palestinians, in a prison management mentality, that if you resist we will take away all your privileges, like we do in prison. You won't be able to work outside. You won't be able to move freely, and you will be punished collectively. This is the kind of the punitive side of it, collective punishment as retaliation.

MEE: The international community shyly condemn the building or expanding of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories. They do not consider it as a major part of Israel’s colonial structure as you describe in the book. How did Israeli settlements begin and was the basis of it rational or religious?

IP: After 1967 there were two maps of settlements or colonisation. There was a strategic map that was devised by the Left in Israel. And the father of this map was the late Yigal Allon, the main strategist, who worked with Moshe Dayan in 1967 on a plan to control the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Their principle was strategic not so much ideological, although they believed that the West Bank belonged to Israel.

They were more interested in making sure the Jews did not settle in densely populated Arab areas. They said everywhere where Palestinians don't live in a concentrated way we can settle. So, they started with the Jordan Valley because in the Jordan Valley there are small villages but it's not dense like in other parts.

The problem for them was that at the same time they drew their strategic map, a new Messianic religious movement emerged, Gush Emunim, a religious national movement of Jews, who didn't want to settle according to the strategic map. They wanted to settle according to the biblical map. They had the idea that the Bible is a book that tells you exactly where the ancient Jewish cities are. And as it happens that map meant that Jews should settle in the midst of Nablus, Hebron and Bethlehem, in the midst of the Palestinian areas.

At first the Israeli government tried to control this biblical movement so that they would settle more strategically. But several Israeli journalists have shown that Shimon Peres, the minister of defence in the early 70s, decided to allow the biblical settlements. The Palestinians in the West Bank were exposed to two maps of colonisation, the strategic and the biblical.

The international community understands that according to international law it doesn't matter whether it's a strategic or biblical settlement, they're all illegal.

But what is unfortunate that the international community from 1967 accepted the Israeli formula that says "the settlements are illegal but it's temporary, once there is peace we will make sure that everything will be legal. But as long as there's no peace we need the settlements because we are still at war with the Palestinians.”

MEE: You say that “occupation” is not the accurate word to describe the reality in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. And On Palestine, a dialogue with Noam Chomsky, you criticise the term “peace process”. This is controversial. Why are these terms not accurate?

IP: I think that language is very important. The way you frame a situation can affect your chances of changing it.

We have been framing the situation in the West Bank in the Gaza Strip and inside Israel with the wrong dictionary and words. Occupation always means a temporary situation.

The solution for occupation is the end of occupation, the invading military goes back to its country, but this is not the situation either in the West Bank or in Israel or Gaza Strip. This is colonisation, I suggest, although it sounds like an anachronistic term in the 21st century, I think we should understand that Israel is colonising Palestine. It started colonising it in the late 19th century and is still colonising it today.

There is a settler colonial regime that is controlling the whole of Palestine in different ways. In Gaza Strip it controls it from the outside. In the West Bank it controls it differently in area A, B and area C. It has different policies towards the Palestinians in the refugee camp, where it does not allow the refugees to come back. That's another way of maintaining the colonisation by not allowing the people who were expelled to return. It is all part of the same ideology.

So I think the word peace process and occupation when they're put together create the false impression that all you need is for the Israeli military to get out of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and to have a peace between Israel and the future Palestine.

Now, the Israeli military is not in the Gaza Strip and is not in that area A. It's also hardly in area B, where it does not need to be. But there is no peace. There's a situation which is far worse than the one that was before the Oslo Accords in 1993.

The so-called peace process enabled Israel to do more colonisation, but this time with international support. So I suggest talking about decolonisation not peace. I suggest talking about changing the legal regime that governs the life of Israelis and Palestinians.

I think we should talk about an apartheid state. We should talk about ethnic cleansing. We should find what replaces apartheid. And we have a good example in South Africa. The only way to replace apartheid is with a democratic system. One person, one vote or at least a bi-national state. I think these are the kind of words we should begin to use, because if we continue to use the old words, we continue to waste time and effort and we won't change the reality on the ground.

MEE: What does the future hold for Israeli military rule over the Palestinians? Are we going to see a civil disobedience movement such as the one in Jerusalem back in July?

IP: I think that we will see civil disobedience not only in Jerusalem but all over Palestine, and this includes Palestinians inside Israel. The society itself would not accept forever this kind of reality. I don't know which means it will use. We can see what happens when you don't have a clear strategy from above that individuals decide to do their own liberation war.

'There was something impressive indeed in the case of Jerusalem when nobody believed that a popular resistance can force the Israelis to retract the security measures that they imposed in the Haram al-Sharif. I think that this may be the model. A popular resistance for the future'

There was something impressive indeed in the case of Jerusalem when nobody believed that a popular resistance can force the Israelis to retract the security measures that they imposed on the Haram al-Sharif. I think that this may be the model. A popular resistance for the future that is not all over the place but in different places.

The popular resistance continues all the time in Palestine. The media doesn't report it. But everyday people demonstrate against the apartheid wall, people demonstrate against the expropriation of land, people go on hunger strikes because they're political prisoners. The Palestinian resistance from below continues. The Palestinian resistance from above is on hold.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.