Gaza's children paint a grim future

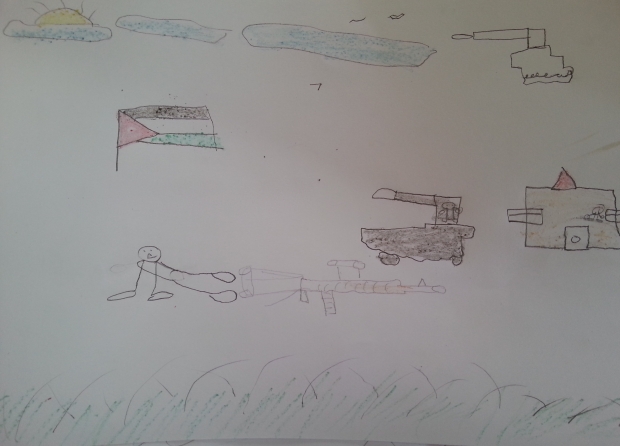

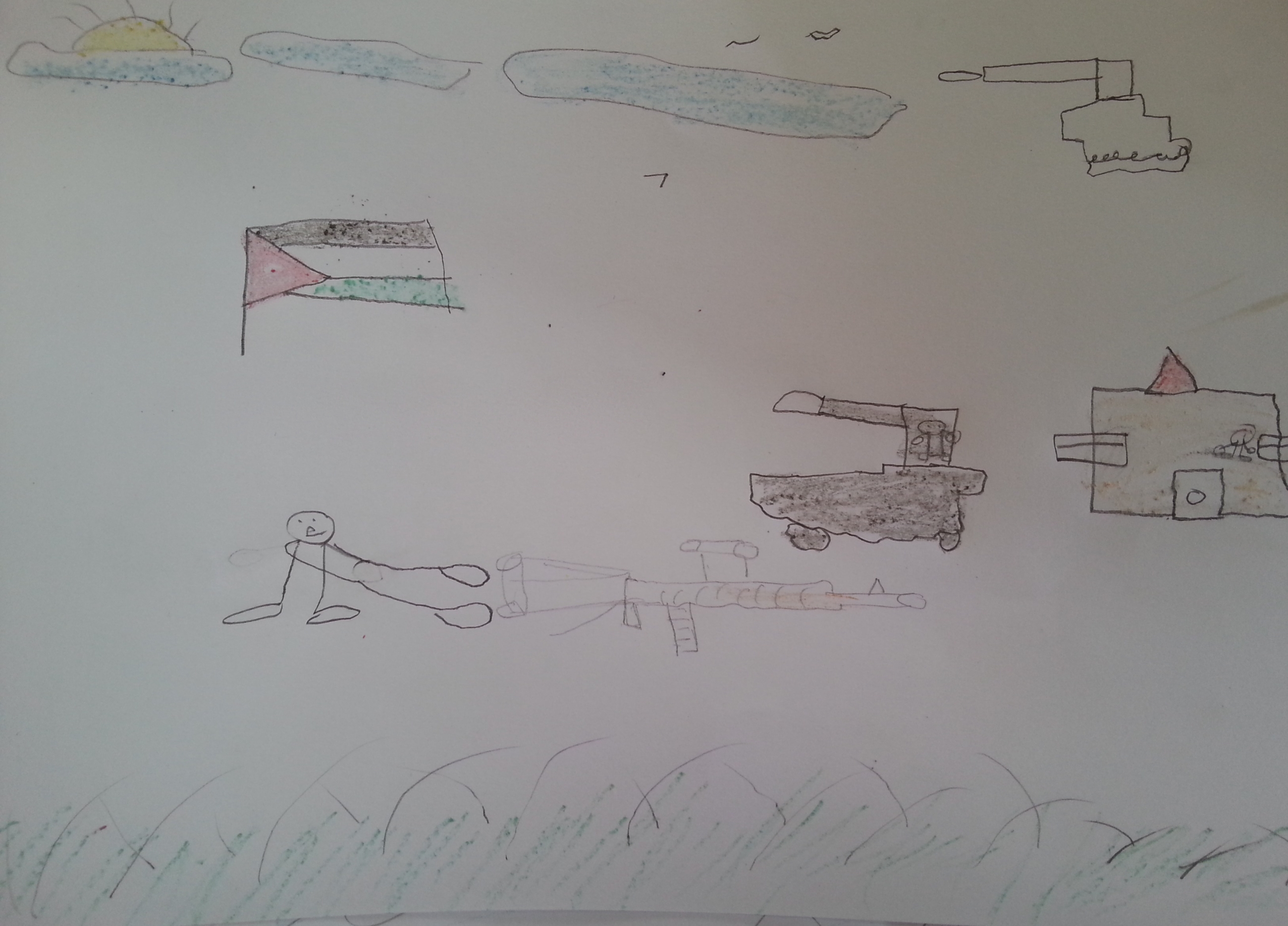

In the wake of Operation Protective Edge, Israel’s latest onslaught on the Gaza Strip, I acquired a series of photographs of drawings by children in the town of Khuza’a in southern Gaza.

Khuza’a had played unwilling host to one of the Israeli army’s many attempts to outdo itself in terms of brutality, with success measurable, perhaps, in the amount of rubble and massacred bodies left behind. The photographs were passed along to me by the Barcelona-based psychoanalyst Lluis Isern, whose colleague in Gaza had sent them to him.

The drawings share many of the features of typical children’s artwork: house, sun, clouds, grass. The scenic similarities come to an abrupt end, however, when one’s eye starts to register additional elements of the landscape - tanks, missiles, fighter jets, and bulldozers.

In a drawing titled Aggression against Palestine, a child has drawn an orange, red, blue, and brown house with five similarly multicoloured people standing outside smiling. Two are holding hands. Above them, four projectiles from a green aircraft descend toward the group, while three from a different aircraft head for the house.

Another depicts a variety of tanks, planes, and guns, interspersed with lines of text such as “Gaza will be victorious”, “Palestine resists”, and a tribute to the al-Qassam Brigades, the military wing of Hamas.

Obviously, the prominence of the house in children’s pictures across the globe reflects the centrality of the home to a child’s universe. So imagine the mental upheaval that ensues when one’s universe comes under regular attack by the Israeli military - or is destroyed altogether.

The traumatic effects of Israel’s wrecking-ball mentality on Palestinians young and old are showcased in the 2009 documentary On Gaza’s Mind, made with the sponsorship of the Catalan Congress on Mental Health Foundation, of which Isern is a member.

The film begins with the late Dr Eyad El-Sarraj, founder of the Gaza Community Mental Health Programme, who describes the essential “disintegration” of society in the Gaza Strip on account of the ongoing Israeli occupation: “Because of the accumulated toxic kind of trauma over the years and years, you have generational problems, from one generation to the other.”

Among members of the younger generation interviewed in the film, constant fear is the predominant theme: fear of warplanes, fear of missiles, fear of having one’s house demolished on top of oneself, fear of annihilation while playing sports.

Rather than being of the monster-under-the-bed variety of childhood anxiety, these fears are continuously validated by environmental stimuli. A child named Hakim from Jabalia refugee camp, for example, recounts an incident in which his friends were killed playing football. He protests meekly: “They weren’t doing anything strange.”

Of course, the only logic accommodated by Israel is that of indiscriminate destruction, a principle that was confirmed when, six months after the filming of the documentary, Operation Cast Lead killed about 400 children in Gaza, in addition to 800 or so larger humans. Hakim’s house was also dispensed with during the three-week affair, and Hakim was subsequently diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This summer’s military operation, meanwhile, gave Israel the opportunity to slaughter some more youngsters engaged in non-strange activity: four boys from the same family playing football on the beach, plus about 500 other children.

Psychological experiments

To be sure, periods of officially titled Israeli devastation in Gaza (Cast Lead, Protective Edge) mean especially concentrated doses of psychological anguish for the population. But mental trauma is a staple of existence in the coastal enclave.

In his book Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation, Saree Makdisi discusses the aftermath of Israel’s supposed “withdrawal” from Gaza in 2005 - which in reality amounted to a continued stranglehold and a “freezing of the peace process”, as then-Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon’s senior adviser, Dov Weisglass, confirmed.

Makdisi writes: “With Jewish settlers safely out of the way, the Israeli air force began staging mock air raids over Gaza - sending jet fighters roaring low over densely populated neighborhoods and breaking the sound barrier in the middle of the night.”

He quotes Dr El-Sarraj’s poetic take on the aerial terrorisation in late September of 2005: “During the last few days, Gaza was awakened from its dreams of liberation with horrible explosions which have shattered our skies, shaken our buildings, broken our windows, and thrown the place into panic.”

Manifestations of panic among the children of Gaza included bedwetting, insomnia, depression, refusal to leave the house, and loss of appetite. According to the Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem, the aim of the sonic boom treatment was transparent: “The sole purpose of these sorties is to prevent the residents from sleeping and to create an ongoing sense of fear and anxiety.”

If we recall that, on an individual basis, forced sleep deprivation is considered to be psychological torture, what does the Israeli approach to Gaza constitute if not a mass torture technique?

The Israeli drones (lethal and non-lethal) that litter the sky in Gaza serve much the same function, minus the sonic booms, while real bombs are naturally also fairly effective in keeping folks awake. The added psychological torment of knowing one is trapped in a sliver of land with no escape route becomes even more acute in times of bombardment.

As numerous observers have noted, captive Palestinian populations have long offered their Israeli oppressors an ideal “laboratory” in which to perfect inhumane methods and then market them abroad in the form of weapons, surveillance systems, and expert counsel and military training for repressive dictatorships and other unsavoury political formations.

Journalist Rania Khalek recently drew attention to remarks made in August to the German magazine Der Spiegel by the head of the Technology and Logistics Branch of the Israeli army: “If I develop a product and want to test it in the field, I only have to go five or 10 kilometers from my base and I can look and see what is happening with the equipment … I get feedback, so it makes the development process faster and much more efficient.”

That Gaza is also a laboratory for psychological torture is clear, although the expertise gleaned from cruel mental experiments is perhaps less straightforwardly marketable. (One envisions an advertisement along the lines of: “Need to inflict PTSD on 1.8 million people really fast? Look no further …”)

Of course, the global prison industry could always benefit from the know-how developed in the world’s foremost open-air prison - the only problem being that many of Israel’s tricks for dealing with its adopted prison population wouldn’t be legally permissible in many jails.

Killing the same bird

Beyond the fact that most prisons don’t let you bomb prisoners or subject them to collective noise punishment, some particularly ethical countries might take issue with the punitive dietary restrictions Israel has been known to wield over Gaza.

Back in 2006, Weisglass acutely explained the pernicious Israeli blockade of incoming foodstuffs and other items necessary for life: “The idea is to put the Palestinians on a diet, but not to make them die of hunger.”

This policy of “calculated strangulation” - the description offered by John Dugard, former United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Palestine - worked like a charm. “[M]ore than half of the families in Gaza now eat only one meager meal a day,” wrote Makdisi in Palestine Inside Out in 2008:

“According to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights in Gaza, more than 22 percent of children under five suffer from malnutrition, and 16 percent suffer from anemia. This will have long-term consequences for their health - stunted physical and mental development are more or less guaranteed outcomes.”

Meanwhile, in a display of double-fisted criminality on the part of the self-appointed prison guards, Israel provokes mental trauma on the one hand and impedes the delivery of psychiatric medication on the other. The phrase “kill two birds with one stone” comes to mind when contemplating the effectiveness of the blockade in both promoting rampant depression - a result of skyrocketing unemployment, claustrophobia, and other Israeli-induced conditions in the Gaza Strip - and blocking folks from receiving proper treatment.

Or maybe a better analogy would be killing the same bird over and over again with every kind of stone imaginable.

One-and-only victim

Despite the disproportionate damage consistently done to Palestinian minds and bodies by Israeli policies and projectiles, Israel’s defining tradition of self-victimisation teaches us that it’s actually Palestinian stones and rockets that are the problem. Israel occupies the position of one-and-only victim of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; never mind when civilians in Gaza do things like perish at a rate of 400:1 vis-a-vis their Israeli counterparts during intensified episodes of the “conflict”.

These episodes inevitably come accompanied by Israeli hysteria over the allegedly unbearable anxiety brought on by air-raid sirens - which, far more often than not, herald the non-arrival of a rocket from Gaza. According to the Israeli line, having to listen to these sirens is way more taxing on the nervous system than, say, having your body ripped to pieces by a fragmentation bomb.

One of the advantages to holding all of the rights to psychological suffering is that the Israelis are able to beef up their wartime casualty counts by tacking on victims of “shock and anxiety”. Were the Palestinians to follow a similar protocol, it would at least simplify the tallying procedure - ie the figure 1.8 million could hereafter be inserted into every casualty slot, at least until there’s a change in population size.

Predictably, the psychological stress suffered by Israeli children is a fixture of sympathy-courting propaganda campaigns. According to the Sderot Media Centre, based in the Israeli city of Sderot on the frontier with Gaza, “[s]tudies have revealed that 70-94% of Sderot's children suffer from PTSD”.

A post-Cast Lead article reports that Sderot kids are “born into a reality of terror” defined by the “Color Red” rocket alert system: “The ‘Color Red’ was not introduced to them in kinder garden [sic] like the rest of us have [sic]; the concept of the ‘Color Red’ was familiar to them pretty much since they learned to say the word ‘Dad’.”

Never mind that a total of eight people have died in Sderot - two of them under the age of 18 - from Palestinian rocket fire since 2001. This is fewer people than Israel has been known to take out in one fell swoop when it bombs women and children sheltering in Gaza schools. There have been no rocket fatalities in Sderot since February 2008, that is, 10 months prior to the onset of Cast Lead.

Whereas Palestinian kids who draw pictures of their homes being obliterated by Israeli weaponry are merely accurately depicting their surroundings, Israeli kids who draw Qassam rockets and the like are acceding to a wildly exaggerated and politically expedient reality. My response: if you are going to raise your kids on the Color Red to justify a genocidal approach to the Palestinians, don’t go complaining if they’re scared.

Forcible disintegration

Lawyer Raji Sourani, director of the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, points out in an August opinion piece translated for the prominent Spanish daily El Pais that “[a] six-year-old child [in Gaza] has already lived through three wars”.

Sourani makes the following plea: “The inhabitants of the Gaza Strip are people like any other. We have the same dreams, the same hopes and the same ambitions. We bleed the same and we cry the same.”

Theoretically, of course, this should be true. But the Palestinians of Gaza in fact bleed disproportionately, and are permitted to continue to bleed thanks to a dehumanising discourse that devalues their blood. When former Israeli prime minister Golda Meir contended that there was no such thing as “a Palestinian people”, she might as well have been referring to their subhuman status rather than to the supposed absence of an ethnic group historically identifying as such.

As Sourani notes, however, the impunity with which Israel commits war crimes doesn’t always go unchallenged. For example, following Operation Cast Lead, “[a]n [Israeli] soldier was sentenced to seven months for stealing a credit card”, while another soldier received 45 days for “firing on a group of civilians carrying white flags and killing two women”.

One effect of Israel’s sustained physical and psychological assault on its favourite non-people is the Palestinian “disintegration” discussed by El-Sarraj in the On Gaza’s Mind documentary. By breaking down the Palestinians physically and emotionally, Israel hopes to achieve an erosion of Palestinian identity, thereby bringing the Zionist enterprise one step closer to glorious fruition.

The breakdown is a comprehensive effort targeting every level of Palestinian existence, from the collective down to the individual. On a macro level, forcible disintegration is viewable in the butchering of Palestinian territory into non-contiguous enclaves, with access between them severely restricted when not prohibited outright.

Community cohesion is further thwarted by the Israeli penchant for playing off different Palestinian political factions against one another. Then there are the alienating divisions that exist between millions of diaspora Palestinians and their compatriots thanks to Israel’s ethnic cleansing program and denial of the Palestinian right of return.

In the documentary, El-Sarraj discusses the intra-familial disintegration that can occur as a result of Israeli-induced trauma, often arising from difficulties in interpersonal communication and self-expression in traumatised family units. Of no help, obviously, is the lack of a proper state able to attend to the mental health needs of its citizens.

It’s also not helpful when children have to witness their parents depressed or otherwise mentally destroyed, sometimes with psychotic conditions as a result of time spent in Israeli jails. As El-Sarraj notes, men tortured in prison sometimes emerge to abuse members of their own family because “torture and violence bring violence”.

What, then, is the prognosis for the future; will Israel’s attempted full-scale demolition of Palestinian-ness breed a mentally deteriorated, submissive population in Gaza fearful to assert itself in opposition to the goals of predatory Zionism? Or will violence beget more violence?

“Normal human beings”

One scene in On Gaza’s Mind features a child named Ahmed - nicknamed “Misho” - who was injured beyond recognition during an Israeli incursion into Gaza in 2008 and was presumed dead by his family for two weeks. A poster prematurely communicating his death hangs in the background as a bedridden Misho (speaking with great difficulty) tries to recount the ordeal with the help of his parents.

An update at the end of the film informs us that Misho has shown no signs of improvement, and that he says he wants to die.

Of course, someone as physically incapacitated as Misho cannot translate his desire for death into a martyrdom operation against Israel - nor would he necessarily want to. But the sentiment nonetheless serves as a reminder of what folks can be driven to do when given no reason to live - and many reasons not to.

It is nothing short of astounding that Israel’s violent inundation of Gaza has not been met with more violence on the part of the Palestinians, despite El-Sarraj’s observation - confirmed by the drawings from Khuza’a - that “the children today … are preoccupied with violent themes. Like killing, shooting, blood, tanks, jeeps. F-16s, flags, machine guns, and so on.”

The other day in Barcelona, Dr Isern commented to me on the therapeutic nature of drawing - of converting one’s pain into something that can be controlled on paper and shared with others. However, he also pointed out that another way of attempting to secure a modicum of control over one’s environment and ease one’s emotional trauma is to band together in a group and attack the source of that trauma.

As is clear from the support expressed in some of the Khuza’a drawings made in tribute to the al-Qassam Brigades, Israel’s psychotic behavior in Gaza has far from disabused Palestinian youth of a belief in armed resistance. According to Isern, Israel has failed to foresee the implications of cultivating next door a population of traumatised children, as some will pursue self-preservation via association with violent groups.

In my view, though, an excuse for perpetual war is pretty handy when you’re in the business of selling battle-tested weapons and usurping territory.

In 2004, Professor Arnon Soffer of Haifa University, a prominent Israeli government adviser and demographic fearmongerer, outlined his thoughts on the future of the Gaza Strip in an interview with The Jerusalem Post:

“When 2.5 million people live in a closed-off Gaza, it's going to be a human catastrophe. Those people will become even bigger animals than they are today, with the aid of an insane fundamentalist Islam. The pressure at the border will be awful. It's going to be a terrible war. So, if we want to remain alive, we will have to kill and kill and kill. All day, every day.”

He continued on to express a solitary “concern” regarding this arrangement, which was “how to ensure that the boys and men who are going to have to do the killing will be able to return home to their families and be normal human beings.”

Clearly, Soffer himself has already avoided the “normal human” option. His concern is not unfounded, however; it simply needs to be applied to the entire Israeli establishment as well as to a population that enthusiastically cheers carnage in Gaza.

Were the Israeli state capable of any sort of meaningful self-reflection, realisations about collective complicity in mass killing might bring on a bit of mental discomfort, maybe even enough to rack up some more victims of “shock and anxiety”.

In the meantime, the quandary of what to do about mental health in Gaza was perhaps best expressed by former Oxfam spokesman Karl Schembri in 2012: “How can you talk about post-traumatic stress interventions in Gaza when people are still in a constant state of trauma?”

- Belen Fernandez is the author of The Imperial Messenger: Thomas Friedman at Work, published by Verso. She is a contributing editor at Jacobin magazine.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo Credit: Lluis Isern

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.