Refugees in Germany fight to unite with their families: 'They destroyed my life'

BERLIN – While Nezar's daughter was celebrating her third birthday last month in Damascus, where she is living with her mother, he was around 3,700km away in his Berlin apartment feeling alone and frustrated that he could not be with his little girl on her special day.

He spoke with his daughter online, as he has done almost every day in the past two years and 10 months, though these conversations often make him feel even worse.

The last time [we spoke], she told me ‘Hello uncle.’ She does not know me, and that breaks my heart

- Nezar, Syrian refugee

“The last time [we spoke], she told me ‘Hello uncle.’ She does not know me, and that breaks my heart,” he said. “My daughter needs her father to protect her, to take care of her. My wife needs me.”

The 38-year-old, who asked to conceal his last name for the safety of his family, is one of thousands of Syrians who have been granted protection in Germany but have been denied the right to bring their spouses and children to the country.

The law places a cap of 1,000 per month on the number of reunification visas granted to family members of people who have subsidiary protection in Germany.

Subsidiary protection is a status just below that of refugee, where asylum applicants are given one year residence permits that can be extended. It is usually given to individuals who cannot be expelled because they risk serious harm caused by human rights violations in their country, like torture or the death penalty, although they have not been individually or directly threatened by persecution.

The number of people impacted by the new law is huge, with most of them being from Syria.

According to the latest public data, there are 140,126 Syrians with subsidiary protection in Germany, while there are between 50,000 and 60,000 people in Syria or in neighbouring refugee camps that are eligible for reunification visas because of their family ties to people with subsidiary protection, according to the Institute for Employment Research.

The German Foreign Ministry already has about 28,000 applications for reunification by family members of Syrians with subsidiary protection, according to Susanne Beger-Blum, a spokesperson from the ministry. She added that the figure is not definitive.

Germany’s interior minister said in a statement that the new family reunification law ensures a responsible balance between the interest of reuniting families and the interest of maintaining the government’s ability to integrate newcomers.

“We have demonstrated our ability to take action and held to our basic position, namely managing and steering migration while also limiting it," Horst Seehofer said.

He explained that responsible immigration policy needed to distinguish clearly between different groups.

"If we treated all protected groups the same, with the same rules for family members to join those already here, then the distinction between those granted limited protection and those with full protection would become meaningless," Seehofer added.

‘I need my family in order to integrate’

The quota of 1,000 reunification visas per month is simply not enough because the demand is much higher, explained Chris Melzer, a spokesperson from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Germany, who has been in touch with many Syrians since the law was approved last month.

"A lot of people with subsidiary protection are not satisfied with the solution the government found because they have been waiting for years for their families [to] be reunited and now they have to wait even more," Melzer told Middle East Eye. "Many of these people are very sad."

I cannot focus on my work. I cannot focus on my German learning. Everyday my daughter cries on the phone… I need my family in order to integrate

- Nezar, Syrian refugee

“How can I integrate if my family is not with me?” said Nezar, who has been learning German and working occasionally as a security guard in a Berlin refugee accommodation facility in order to be able to send money to his family in Syria. “I cannot focus on my work. I cannot focus on my German learning. Everyday my daughter cries on the phone… I need my family in order to integrate.”

'The natural right of parents'

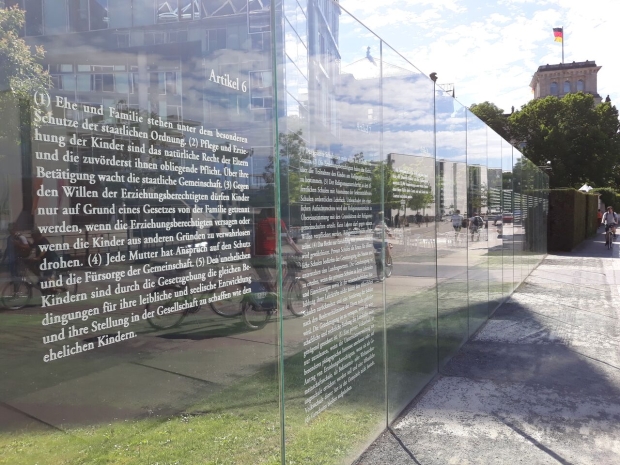

The German government’s welcoming approach towards refugees in the summer of 2015 was the reason Nezar chose Germany as the final destination of his flight from Syria. Before he left for Europe, he had read that refugees were entitled to family reunification according to German law and that the German constitution declares, “The care and upbringing of children is the natural right of parents.”

Nezar then embarked on a gruelling weeklong trip through Europe by foot, bus and train from Greece to Macedonia to Serbia, then from Croatia to Austria and finally to Germany. During this journey he slept a total of five nights on the streets and in forests with other Syrians who were on the route .

Throughout the trip, Nezar took comfort in the assumption that once German authorities recognised him as a refugee, his wife and daughter would be able to travel to Germany on a safe and legal route.

The pictures of the children crying after being separated from their mom[s] at the border thanks to Trump’s policy were hard to bear...That we do not see these pictures in Germany each day, does not mean that this suffering and pain does not exist

- Bellinda Bartolucci, a legal policy advisor at ProAsyl

Between 2010 and 2013, Germany granted nearly 55,000 residence titles per year for the purpose of family reunification for refugees, including those with subsidiary protection and refugee status. In 2014, it granted 63,677 titles and in 2015, the number rose further to 82,440.

But in the beginning of 2016, as Nezar was waiting for his asylum interview to happen, the German government’s policy towards refugees started to become less welcoming. Faced with growing political pressure to decrease the number of refugees settling in the country, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s administration approved a two-year freeze on all family reunifications for people with subsidiary protection.

Following extensive, tense parliamentary debates between right-wing parties who wanted a stricter cap and left-wing parties who argued for unlimited family reunification, the new family reunification law was drafted and approved in May of this year.

Nezar’s asylum process ended in October 2016. He does not know why German authorities decided to grant him subsidiary protection instead of refugee protection, but as soon as he learned about the decision, he realised it would be a very long time before he could hug his wife and daughter again.

The thousands of Syrians who are in the same family separation situation as Nezar don’t yet know how the German government will choose which family members will be granted reunification visas every month. The criteria to decide who will be amongst the 1,000 per month is currently still under consideration within the federal government, according to Beger-Blum.

“In our view, it is a very big scandal what is happening here,” said Bellinda Bartolucci, a legal policy advisor at ProAsyl, a refugee rights organisation.

Asked to compare Germany’s policy towards people with subsidiary protection to the family separation policy Donald Trump’s administration recently implemented, and later reversed as a result of public pressure, Bartolucci indicates there is some resemblance.

The US government’s policy was to separate families crossing the US border illegally and in some cases seeking asylum, then taking the children to government custody alone while sending their parents to jail. While the two policies are different, in both cases governments are restricting family life in order to deter unauthorised migration.

“The pictures of the children crying after being separated from their mom[s] at the border thanks to Trump’s policy were hard to bear,” Bartolucci said. “That we do not see these pictures in Germany each day, does not mean that this suffering and pain does not exist.”

Protesting for reunification

The pain Bartolucci mentioned is what motivated Nezar to attend a series of demonstrations against Germany’s new family reunification law, organised by a coalition of Germans and Syrians that goes by the name “Familienleben für Alle!” – Family Life for All. The spokesperson for this group is Mohamad Malas, a 33-year Syrian who came to Germany in October 2015 through the same smuggling route as Nezar. He has also been granted subsidiary protection.

When he first arrived in Germany, he thought his wife would obtain a family reunification visa within three months, but 30 months have passed and he still has no idea when they will meet again.

“I feel cheated,” Malas said. “We did not do anything to deserve this punishment. This is not right. Family life is a fundamental right.”

In the past month, Malas has been amongst the organisers of the demonstrations against the new family reunification law. This past Saturday, Malas and Nezar took part in a large protest in the centre of Berlin. They both held up a sign that read: “Familienleben für Alle!” and distributed brochures explaining how the new family reunification law impacts them and many others.

They seem energised by their struggle, but their reality has not changed. “They destroyed my life,” Nezar said with a hopeless, bitter smile. “Now I am smiling but inside me I burn, and every day I cry, [a] strong cry: why is this happening to me?”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.