Salt Houses: Tackling Israel-Palestine with a poet's licence

Hala Alyan's debut novel, Salt Houses (2017), covers the wanderings of a Palestinian refugee family's four generations across Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, France and the US, from the Nakba until the present day.

Each slice of the artful narrative centres around a meaningful moment in a family member's life. The interconnected vignettes create a three-dimensional artwork much bigger than its constituent parts.

Whether addressing the fears of a child, the worries of a mother, the frivolity of a teenager in Paris, or the confused thoughts of an elderly refugee suffering from Alzheimer's, Alyan is convincingly insightful. She sounds the depths of her characters' psyches, delving into their inner thoughts and hesitant ruminations, all with a poet's licence.

Conspiratorial backstory

So how did Alyan, a practicing psychologist and prize-winning poet, gain entry into the US publishing world, where both profits and politics are skewed against her theme?

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Assumedly, there was some give-and-take between author and publisher, mediated through an expert literary agent. In the process, what concessions might this poetic Palestinian author have made to gain acceptance within the openly pro-Israel US literary field?

In one scene, Alia, a central protagonist, chats with Telar, a young Kurdish woman who she meets on the beach in Kuwait. Telar describes the atrocities committed by the regime of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein: "The army rounded them up, slit their stomachs in front of our houses, shot the knees of anyone who cried out. To the women ... they did awful things. They made husbands watch. They made little children watch."

The fact that the couple's life events - even if spotty in recollection - constitute the backbone of the narrative, hints at the elision of Palestinian culture, history and rights

This is well-deserved censure, regardless of one's stance on the Iraq War, which was supported by Israel. It also brings to mind an earlier account in the novel of Israeli soldiers raping a Palestinian woman in Haifa, which balances the sympathy scale, if not tips it in favour of Palestinians.

However, another attack seems to build up early on in the book, as Alyan artfully conjures up a dark miasma of conspiratorial backstory to the mosque attendees in Nablus - a litany of hints that befit the Western world's imagined atmosphere of a Hamas cell, even though this segment predates the movement's establishment. From here, it is easy to generalise to all of Gaza and Palestine.

Western media conceptions

The suggestive name of a prostitute in a refugee camp, Aya - the name of a Quranic verse - also reflects on Islam. To Palestinians, such glum interpretations may sound overwrought, but this is the reality of Western media conceptions.

At the same time, all three main examples of religious men in the novel - the refugee imam in Nablus, the pious physician husband of the family's daughter in Amman, and her rescuer from drowning as a teenager in Kuwait - shine as gentle individuals backed by a benevolent and responsive Allah.

In the end, my balance sheet comes out tipped towards the pro-Palestinian side. Admittedly, Alyan's sentiments are less direct than is typical for Palestinian writers; most of the strongest pro-Palestine points shine in flashbacks and memories, rather than directly witnessed events.

Towards the end, readers gain access to Alia's spotty and confused recollections and to the private letters of her husband, Atef. He wrote them to his dead comrade, the clan's martyred hero, Mustafa, whose burial site no one knows.

The fact that the couple's life events - even if spotty in recollection - constitute the backbone of the narrative, hints at the elision of Palestinian culture, history and rights. What sticks with the reader is their grief, anger and confusion.

A garden in Palestine

One evening after sunset, Atef's grandchildren find him with his hands covered in dirt, bleeding from pulling out the wildflowers his wife never liked in her garden. Disturbed by his grandchildren having discovered his secret of "singing Mustafa's name" to his Israeli torturers, he says: "Your grandmother used to live in a house with a garden. In Palestine. With her brother. I used to go there a lot."

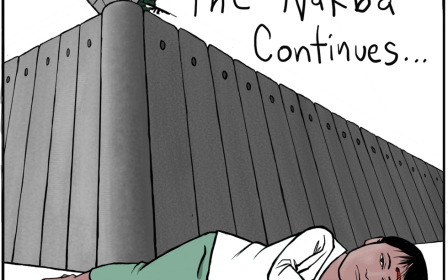

This type of scene is what is most touching about the novel; a soft sell in place of the usual shrill cries of foul play about the historical crimes of the Nakba. Still, I regret the lack of focus on the land itself, the real underlying cause of the Israel-Palestine conflict, despite Israel's diversionary claims of historical, cultural and religious differences.

I am also uncomfortable with the vague sense of equivalency in the novel between Israelis and Palestinians. No assumption of such balance between aggressor and aggrieved is acceptable to a Palestinian, so I'm sure this was not the author's intention.

In the end, I am satisfied that the author did not compromise her artistic integrity in any way. Having proven her worth in this David-and-Goliath bout of author versus publishing industry, let us see Alyan really stand up to the US Zionists in her next prize-winning opus.

- Hatim Kanaaneh is a retired public health physician and a Palestinian citizen of Israel who practiced in rural Galilee, where he founded the Galilee Society for Health Research and Services. In retirement, he published a book of memoirs and a collection of short stories.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Palestinian man waves his national flag during a protest calling for a lifting of sanctions on Gaza, in the West Bank city of Ramallah, on 23 June 2018 (AFP)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.