'You have to go deeper': Islamic art comes alive at Jameel prize in London

LONDON – From the mosaics of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus to the calligraphy inscribed on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, Islamic art is usually associated with the architectural wonders of the ancient world.

However, upon entering the gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where the Jameel Art Prize winners and finalists are being exhibited, it is clear that the Islamic tradition has an important place in modern art.

From architects to fashion designers and visual artists, this year’s eight finalists all demonstrate how Islamic motifs remain significant in the contemporary age.

The Jameel Art Prize is a biennial award celebrating the embodiment of the Islamic tradition in contemporary art and design.

In its fifth edition, this year’s prize of £25,000 ($32,800) was for the first time given to two finalists: Marina Tabassum and Mehdi Moutashar. Their work was shown alongside six runners-up of the prize on 27 June, with Fady Jameel, president of Art Jameel, leading the ceremony.

Tabassum, a Bangladeshi architect, was awarded the prize for her exceptional design of the Bait ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka.The fact that the resources [to build the mosque] were so limited meant that in a way it remained very basic, very elemental

- Marina Tabassum, architect

The mosque is a haven from the hustle and bustle of the Bangladeshi capital and is described by many as a spiritual sensation.

"I find it to be a refuge," Tabassum told Middle East Eye in a telephone interview from Dhaka. "If you just go in and sit inside, you are away from a lot of things."

The mosque, completed in 2012 after five years of construction, is an example of how skilled architectural design can manipulate even the cheapest materials, in this case brick and cement, resulting in outstanding results.

"The land was donated by my grandmother, but there weren't really the resources to build it," Tabassum, who is 49, said. "The fact that the resources were so limited meant that in a way it remained very basic, very elemental."

Tabassum's design stands apart from traditional mosques. There is, for example, no minaret and no dome, and no ornamentation whatsoever is used. Instead, the architect turned to a more minimalist structure that relies on natural elements.

Dapples of light

In the main hall, natural light dapples onto the floor through holes in the ceiling and glows through apertures in the walls.

The light creates the spiritual context

- Marina Tabassum, architect

A sense of spirituality is created through Tabassum's careful consideration of the climate the mosque is situated within. Understanding the importance of air flow within a city as humid as Dhaka, Tabassum designed a "cross ventilation" system using tunnels and open-to-sky courts that allow for air to flow in and out seamlessly.

Visitors can experience a sense of calm and relief away from the intensity of the city.

"Bangladesh is a Muslim majority country, so everything is in the tradition, philosophy and practice ... [but] it's not similar to what you see in the Middle East," she continued. "There is a different context, the climatic context, the historical context and also the culture that was prevalent before Islam."

Islamic art meets European modernism

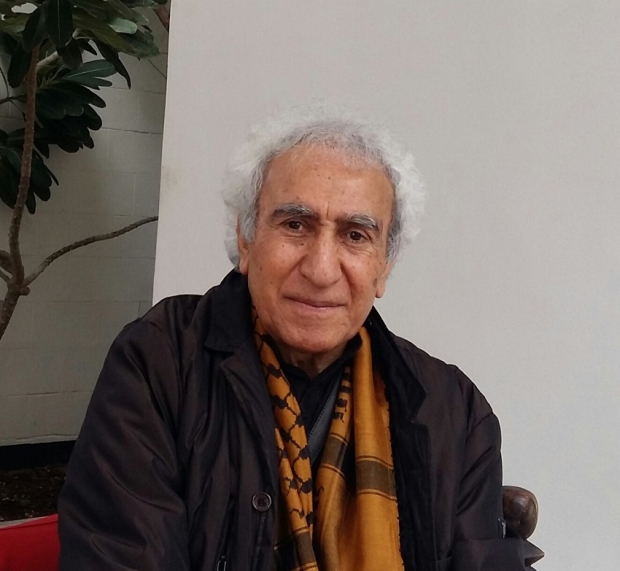

Visual artist Mehdi Moutashar is the other joint-winner of the prize. His unique abstract works intertwine influences from the Islamic art of his native Iraq with European modernism.

In his sculpture, Deux plis à 120, two black metal plates are folded in half, creating geometric shapes that meet at the tip of two angles. The sharp lines and perfectly measured forms are reminiscent of geometric abstraction from 20th century Europe. However, its steep, diagonal placement on the wall clearly echoes Arabic calligraphy.

A lot of people in Islamic or Arabic culture think that Islamic culture was a kind of decoration. But it is not, it is something more profound, more complicated and more modern

- Mehdi Moutashar, artist

“A lot of people in Islamic or Arabic culture think that Islamic culture was a kind of decoration. But it is not, it is something more profound, more complicated and more modern,” he said.

It was upon his move to France that Moutashar discovered clear parallels between Islamic art and European modernism.

"In Islamic art, like in calligraphy or Arabesque, space and precisely measuring space is one of the main points," he told MEE from his studio in Arles, France. "For example, if you look to Arabic calligraphy, you find that ... they start to measure the space where they write the letters by the thickness, by their qalam - the tool with which they write."

"I discovered that those points are also important in modernity; in Cubism, Constructivism, Russian Constructivism, and in the Bauhaus," he said.

In Moutashar's Deux carrés dont un encadré, a blue square sits against a white background. Below it, a second square formed within an octagon extends off and out of the wall. At the same time, the square echoes the calligrapher's diamond, and the bright blue aligns itself with the colour used to decorate walls in Islamic architecture.

Moutashar described the use of a similar colour blue in the central mosque in the original city of Baghdad which stood there centuries ago. "I found it amazing to continue using this colour as a kind of sign from my home," he said.

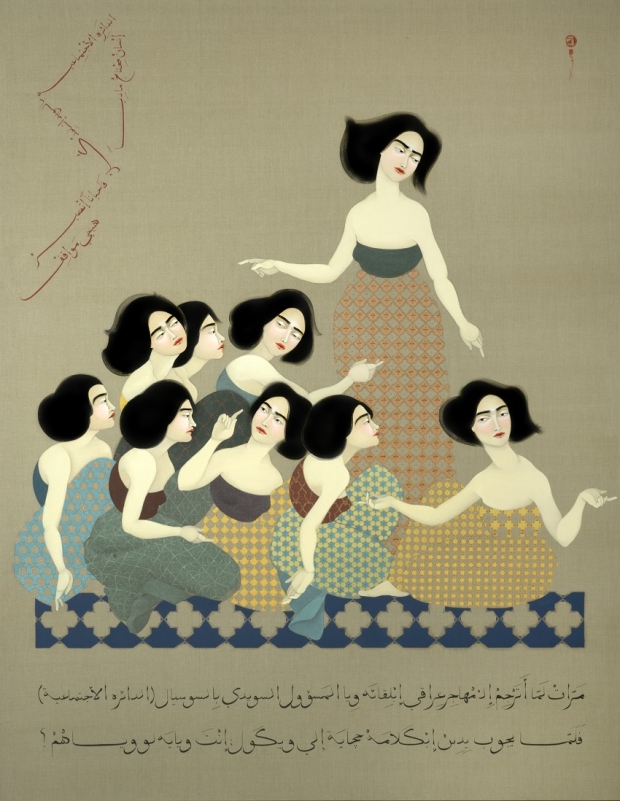

Iraqi artist Hayv Kahraman's paintings merge the ideals of beauty from Renaissance art with influence from 14th-century Iraqi manuscripts and Persian miniature painting to comment on the role of women in society. She also is inspired by her personal struggles of living in Europe as a refugee after having moved from Baghdad to Sweden in 1991 during the Gulf War at the age of 10.

In The Translator, for example, the white skin and delicate features of the women clearly align with the idealised representation of women in Italian Renaissance paintings, while the flatness of the work and composition of the women draw clear parallels to Persian and Iraqi illuminated manuscripts.

The Naqsh Collective, by sisters Nisreen and Nermeen Abu Dali, both finalists in the Jameel Art Prize, is a reinvention of the traditional craft of Palestinian cross-stitching embroidery in a contemporary way by applying the patterns to wood and marble using digital technology, ensuring that it will be passed down to future generations.

Symbolism of the cube

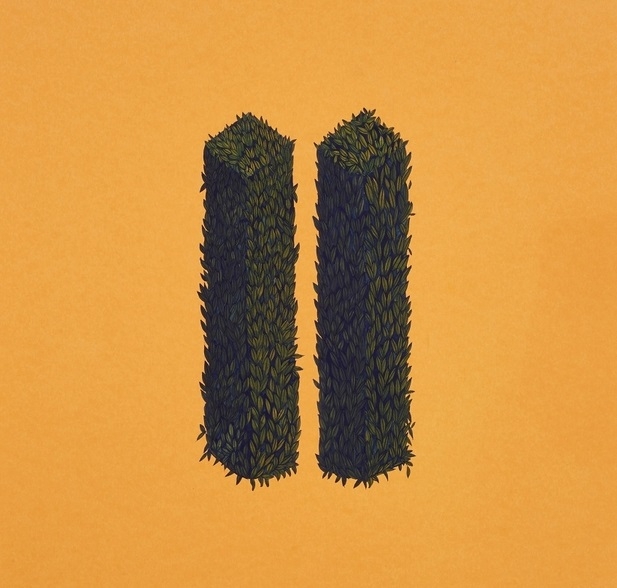

In one of the darker corners of the gallery, a series of warm yellow and orange canvases glow from out of their frames. As the viewer draws nearer, a sequence of miniature paintings appears. Upon closer look, a series of minute birds burst out of the frame, extending onto the walls and floor.

This is the work of Pakistani artist Wardha Shabbir. Although she does not think of herself as a miniature artist, she incorporates its principles into her contemporary practice.

The first thing that you have to do is break the social norm in your family and then in your surroundings because this is a girl and she wants to be a painter

- Wardha Shabbir, artist

The influence of 14th century and Pahari miniature painting is evident in her traditional representations of nature.

In A Cube, a hedge is set against a warm yellow background at the centre of the canvas.

"The cube itself is like an omnipresence of something. It's a symbol in Islamic art," she says, referring to the Kaaba, which stands at the centre of the Grand Mosque in the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. "If you look at the most famous and powerful symbol of Islam, it is the Kaaba, which is a cube," Shabbir said.

Discovering the self

Underlying Shabbir's practice is the Islamic concept of Sirat al-Mustaqueem. Together, the words refer to one's journey to righteousness. However, Shabbir explained that she is more interested in just the Sirat, the pathway we are all travelling on which is determined by our own decisions and actions.

I absolutely don't feel any pressure of giving up my career. In fact, I think it will add more to my understanding of life

- Pakistani artist Wardha Shabbir

"Being a female Muslim in Pakistan, it was not easy to choose painting as a career," she said. "The first thing that you have to do is break the social norm in your family and then in your surroundings because this is a girl and she wants to be a painter."

Being the first woman in her family to pursue a career in art, Shabbir had to use self-determination to follow her dream. She was fortunate enough to have parents who supported her decision.

Now in her 30s and married with her first child on the way, Shabbir has no intention of halting her career.

"It was not very easy for me to become an artist; I had to break the social norms," she said. "I absolutely don't feel any pressure of giving up my career. In fact, I think it will add more to my understanding of life."

Through her art, Shabbir is able to explore her personal Siraat while also setting an example to young women in similar positions.

"Through my own practice ... I am trying to grow as a person and teach other females as well that this is how you can choose, and it shouldn't be a taboo to become a female painter," she said. "I have to become that pathway for other people as well."

*The Jameel Art Prize will be on display at London's Victoria and Albert Museum until 25 November.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.