After Idlib, how can Syria rebuild?

As the Syrian rebels leave Idlib, it is clear that President Bashar al-Assad has won the civil war that has torn apart Syria for more than seven years.

Most rebel groups have yielded to pressure from the Russian- and Iranian-backed army; the Islamic State (IS) is considerably weakened and only controls a very small area; and the Kurds, who control significant territory in the north, have been let down by the US amid Turkish pressure.

From a military perspective, Assad is winning the game. A reversal of fortunes now appears impossible. But the years of war have left a heavy balance sheet: more than 500,000 people are estimated to have died, while more than 10 million have fled the country or been internally displaced. By some estimates, it will take up to $400bn to rebuild Syria.

Other estimates range from $100bn to $350bn, with some as high as $1 trillion.

Driven by vengeance

While the Syrian regime has called on refugees to return home, it actually cares less about this issue than about the infrastructural damage throughout the country.

Indeed, most Syrian refugees opposed Assad, and many have seen their family members killed or imprisoned by the regime's army. To Assad, a significant number of these refugees are potential “terrorists” who, driven by vengeance, pose the risk of fuelling another uprising at the slightest sign of instability.

The refugee outflux from Sunni majority areas has led to a dramatic demographic shift, upon which the regime will aim to capitalise by organising a complementary geographic shift

In addition, the exile or internal displacement of almost half the population has allowed Assad to lead a country that is more politically and ethnically homogenous.

In August 2017, the Syrian president said in a speech: “We lost the best of our youth and our infrastructure … But in exchange, we won a healthier and more homogeneous society in the true sense.” Last July, Jamil al-Hassan, head of the Air Force Intelligence administration, reportedly noted that "a Syria with 10 million trustworthy people obedient to the leadership is better than a Syria with 30 million vandals".

Ethnic homogeneity is undoubtedly the greatest guarantee of stability for the Syrian regime. The president hails from the Alawite minority and has built his legitimacy around defending minorities, while the overwhelming majority of Syrians are Sunni.The refugee outflux from Sunni majority areas has led to a dramatic demographic shift, upon which the regime will aim to capitalise by organising a complementary geographic shift, encouraging Shia and Christian residents to populate "useful Syria" - the coastal areas and the Lebanese border, Damascus, Aleppo, and the major cities of western, southern and central Syria - and sending Sunnis outside of this area.

Collaborating with enemies

For this plan to be implemented, however, the country must first be rebuilt - and to do this, the regime has to collaborate with its enemies.

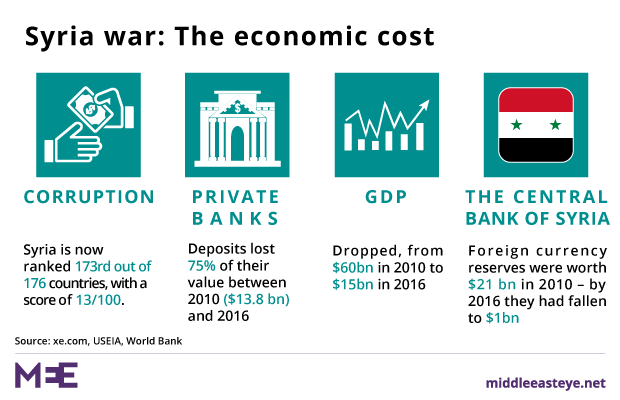

The reconstruction will cost hundreds of billions of dollars, and after seven years of war, state coffers are empty. Despite the end of fighting, Damascus will find it difficult to jumpstart the country’s economy, with much of its key infrastructure destroyed.

Before the war, fossil fuels accounted for a third of Syria’s total exports, at $3.5bn annually. It is currently impossible to reproduce this output, as much of the country’s oil infrastructure was destroyed in fighting between rival factions. Although the reconstruction of these facilities is underway with Russian help, Damascus may end up with a smaller share, as significant royalties will be destined for Moscow.In addition, while Europe accounted for 95 percent of Syria’s oil exports prewar, extended sanctions will force the country to look to other export markets - but routing to Asia remains logistically difficult.

Syria’s traditional allies, Russia and Iran, will be of little use in the reconstruction process, lacking the financial means. Tehran is in the midst of a serious economic crisis amid tightening US sanctions, while Russia, behind its great military power, has approximately the GDP of Spain.

While China has the capacity to finance part of the reconstruction, it remains wary of investing in Syria amid omnipresent corruption and the lack of any guarantees of a return on investment.

Funding reconstruction

The US, EU and Gulf countries could raise the necessary reconstruction funds, but they have been politically hostile to Assad, backing rebel groups to remove him from power. Assad has already rejected an offer from Saudi Arabia to fund reconstruction in exchange for a diplomatic turnaround on Iran.

If the war was a victory for the regime, it will be complete once reconstruction is underway. But Assad heads a regime whose war has paradoxically weakened its power.

Intelligence services have returned to the peak of their influence, and Syrian sovereignty has been undermined by the crucial role Iran and Russia played in saving the regime as well as the presence of other actors including Turkey and the US.

If no solution is found, Assad will have won the right to be at the head of a country sharply fragmented by internal forces and external interference - a country in ruins, whose remaining faithful, tired of the economic slump, could also represent a threat to the regime.

Indeed, the support for Assad comes from a Sunni bourgeoisie, whose interests are closely linked to the survival of the regime, as well as the minorities who are concerned about their rights. One of the consequences of the demographic changes that have taken place across Syria is that the regime's argument about protecting minorities will no longer be a sufficient factor to sustain unconditional support for it.

In the same way, the lack of economic prospects for future growth could see the support of the Sunni bourgeoisie crumble.

- Anas Abdoun is a geopolitical analyst for an energy sector firm. His area of research is the Middle East and North Africa region. He is also a regular contributor to numerous sites specialising in prospective analysis and political risk.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Ruins of buildings can be seen after government bombing in the southern edge of Idlib province on 9 September 2018 (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.