The British Museum's new gallery: A history of Islam in over a thousand objects

LONDON – Walking into the new Islamic art gallery at The British Museum is unlike any other experience. Far from the dimly lit and stuffy interiors that often house ancient artefacts, the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World is bursting with natural light.

From the moment you step into the first room, you are greeted with timeless objects such as the remarkable "Stone Inscription" from 9th century Egypt with a quotation in early Kufic script on marble, saying, "In the name of Allah".

This sets the tone for the marvels that follow: from a beautiful brass tray inlaid with silver and gold, covered in detailed medallion motifs, from late-13th century Iran, to an elaborate Sudanese lyre from the late 1800s, embellished with beads and coins, and more originating from Cairo, Britain and the Indonesian island of Sumatra during the Dutch colonial era.

Spread over two galleries in the centre of the museum, the display exhibits over 1,600 artefacts from the Islamic world, originating in the Middle East, Africa and South East Asia.

Now the collection has been relocated to the heart of the museum in two galleries, increasing the space by a third. The new wing, supported by Albukhary Foundation, a non-profit organisation based in Malaysia, shows pieces that have never been displayed before.

Being able to listen to the oud as you look at the Arabic lutes on display, or watching a calligrapher write in Arabic as you look at the scripture, brings the works to life in a new way

"In our previous gallery, we showed mainly the central Islamic lands: the Arab lands, Iran, Central Asia, and parts of India. In this gallery, we really extended so that it would be much more true to the reality of Islamic visual culture," she explains.

The two rooms are divided between the rise of Islam in the 7th century up until the 1500s, and from the 1500s to the present day. The central spine follows a chronological order, allowing for the thematic exploration of the history of Islamic art on the edges of the gallery, such as objects from daily life, and the spoken and written word.

Cross-cultural influences

Alongside the artefacts are quotes, translations, and video and audio extracts that give the viewer a sense of the Islamic world as it was at the time.

Being able to listen to the oud as you look at the Arabic lutes on display, or watching a calligrapher write in Arabic as you look at the scripture, brings the works to life in a new way.

"The thing we wanted to do within these cases was not just name dynasties and time periods ... but evoke something about the world and the time and the place people lived in."

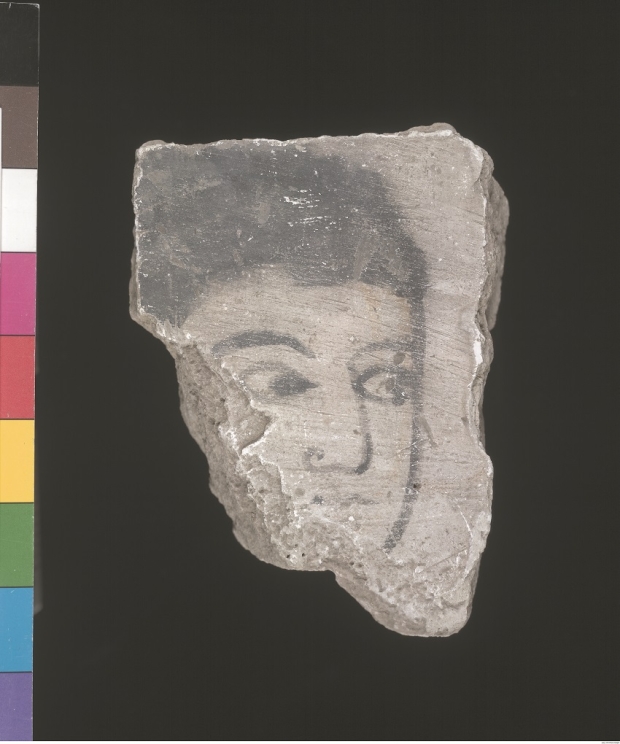

On entering the gallery, one of the first display cases to the right hosts a wonderful assortment of fragmented artefacts, excavated from Samarra city, in central Iraq.

I was under the impression that paintings of humans and animals were prohibited in Islamic art, so it is quite a surprise to see it here

- Julie, a visitor to the gallery

An anonymous viewer at the time wrote: "He who sees it is delighted," reflecting on his experience of the city.

From abstract motifs carved in plaster, to glass mosaics and mother of pearls to paintings, the collection gives us a glimpse of the immense splendour of the palaces and private homes of Samarra, which was founded as the imperial capital city in the 9th century by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu'tasim.

Julie, one of the first visitors to the new gallery, looks at a figure painted in stucco from the 9th century. She remarks: "I was under the impression that paintings of humans and animals were prohibited in Islamic art, so it is quite a surprise to see it here."

Progressing through the dynasties, it is fascinating to see how the unique Islamic style became more intricate and defined over the ages.

Symmetry and geometry

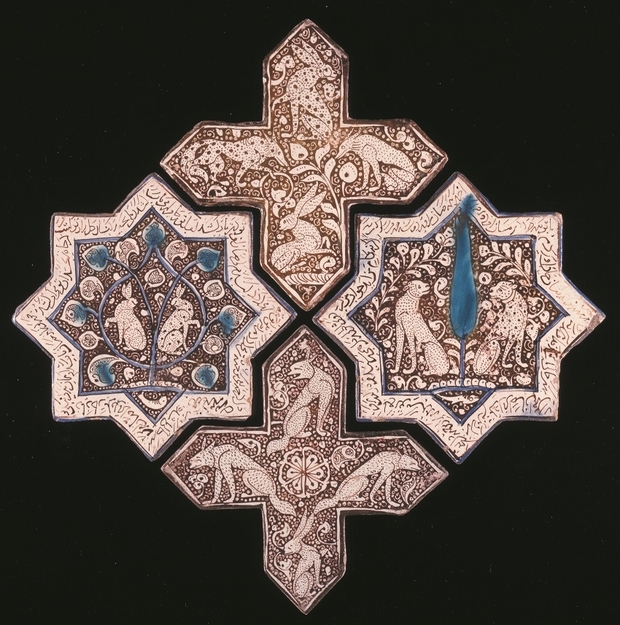

Star and Cross Tiles from Iran is particularly exquisite. Dating from the late-13th century AD, the combination of star and cross tiles exemplifies the symmetry and geometry that has come to define Islamic art.

The tiles are thought to have once belonged to the interior of the Imamzadeh Ja'far shrine in Damghan, Iran. Rabbits, wolves and wild cats mirror each other in between blossoming foliage.

Persian calligraphy recounting passages from the Shahanama (Book of Kings), which is more than 1,000 years old, borders the sides. An epic poem of 50,000 verses, the Shahanama explores the reign of 50 monarchs from the start of documented Arab conquests of Iran.

One of the things that people might be surprised about is that [globalisation] is not new ... it is as old as time

- Dr Ladan Akbarnia, curator

The rest of the room is filled with ceramics and lamps. Some are made of enamelled glass embellished with blue Arabic scripture quoting the Quran, while others combine blue and red to create floral motifs that strongly resonate with the Chinese lotus. There are also inlaid incense burners and astrolabes, a device used by early astronomers to tell time by measuring the altitude of the sun, moon and stars, as well as a navigational device.

Such objects reflect the phenomenal advances in science, algebra, astrology, and literature that occurred in Baghdad, Cairo and Cordoba during the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th century to the 13th, while Eastern Europe was deep in its dark ages. For over 700 years, the international language of science was Arabic.

For example, there is a 15th-century tray emanating from the porcelain centre of Jingdezhen in China which resembles a similar one from the Mamluk Sultanate, replacing brass with traditional blue and white Chinese porcelain.

"One of the things that people might be surprised about is that [globalisation] is not new ... it is as old as time,” says Akbarnia.

The cross-cultural influence is even clearer in the second room, which explores the Islamic world from the 1500s to the present day. The central part of the exhibition delves into the art from the three major dynasties of the period: the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals.

A highlight from the Ottoman dynasty includes the Iznik Basin. Dated to the 16th century, the basin blends the typical Islamic blue found in the earliest architecture of Islam with Chinese floral imagery to create a style unique to the town of Iznik, southeast of Istanbul.

On the side of the galleries, the displays continue to explore the wonderful objects from quotidian life: from textiles to oral traditions, to music and puppetry.

The textiles are particularly fascinating as they show how worldwide influences impacted the fashion of the time. Child’s Outfit shows a chemise, split skirt, and leggings designed for a young girl. Dating from the 19th century, Akbarnia explains that the style became in-vogue when a ruler of the Qajar dynasty, who reigned over Iran from 1848-1896, travelled to Europe.

"Nasir al-Din Shah was one of the most famous Qajar rulers," she says. "[He travels to] Paris and sees the ballet and is so obsessed with the fashion that he brings it back for his entire harem." Thus, Western styles became interwoven in the fashion of Qajar Iran.

"We have a whole section dedicated to storytelling, starting with oral traditions and how stories were told over time, translated into other languages ... and became illustrated in books," Akbarnia explains.

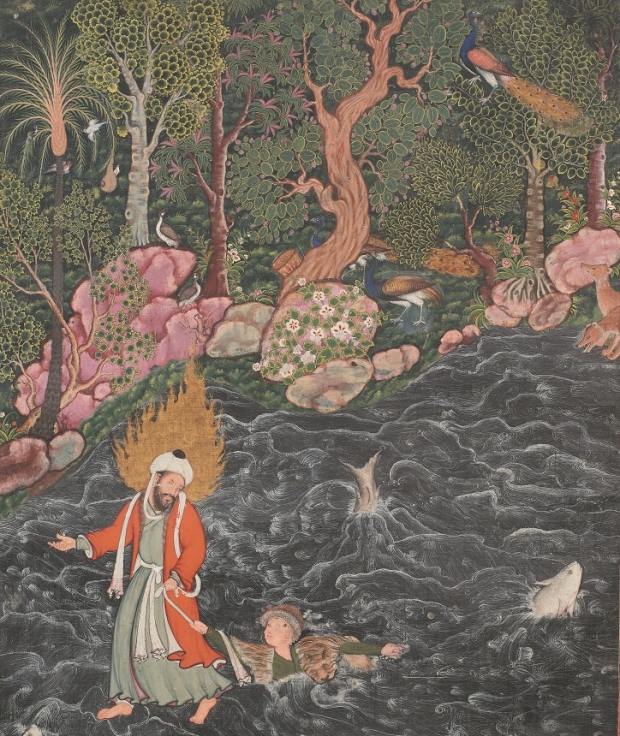

One striking work is a manuscript from the Hamzanama from the 16th century, based on a series of legends about Amir Hamza, the uncle of Prophet Muhammad, which were passed down the generations through storytelling and describe him in a variety of valiant acts, such as his defeat of a two-headed lion with one blow of his sword.

On display is a page from a manuscript commissioned by Akbar, considered the greatest of all Mughal emperors and who ruled most of India and Pakistan in the 16th and 17th centuries. "He [Akbar] liked listening to these stories being recited so much that he commissioned a royal manuscript to be made," says Akbarnia.

Rhapsody in blue

One of the paintings depicts the prophet Elijah, known to Muslims as Ilyas, who is mentioned in both the Bible and in the Quran, saving Nur ad-Dahr, the grandson of Amir Hamza from drowning. Water gushes out of an idyllic landscape of fruitful trees, blossoming flowers and animals, leaving one visitor to remark that it "looks like paradise".

Akbarnia describes a "great collaboration with the Prince's School of Traditional arts, where we've had an artist filmed recreating the image so that people could see how the illuminations get to this point."

Against the back wall of the gallery is an immense series of works by contemporary British-Pakistani artist Idris Khan. The series, titled 21 Stones, references the ritual that takes place during the Hajj pilgrimage when stones are thrown at pillars to symbolise the Stoning of the Devil. Twenty-one blue canvases line the wall recreating the impact of the stone hitting the pillar.

The gallery also holds a space for temporary exhibitions, which will change every six months to two years. The first temporary exhibition hosts a wonderful collection of textiles and artefacts drawn from the collection of the Islamic Arts Museum in Malaysia, established by the Albukhary Foundation, which uses the space to explore the popular Arabesque motif seen throughout Islamic art.

The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World is an outstanding achievement which attests that the influence of Islamic art extends far beyond the Middle East and continues to inspire artists.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.