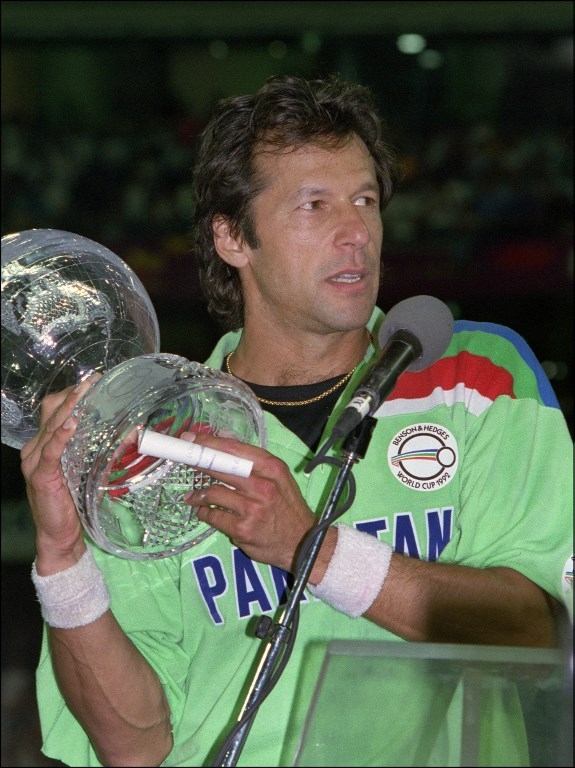

Not cricket: As Pakistan's Prime Minister, Imran Khan is facing his greatest test

ISLAMABAD - Imran Khan’s inauguration as Pakistan prime minister in August marked the culmination of a two-decade personal campaign to break the country's two-party mould.

His journey to the top has been marred by pitfalls. In one election he only obtained a single seat. He was ridiculed and at times written off.

Khan set up his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan Movement for Justice) political party in 1996, four years after stepping down as captain of his country’s cricket team.

He had recently led Pakistan to a famous victory in the Cricket World Cup, and for many years was one of the most charismatic and glamorous sportsmen in the world.

As a politician he swiftly established an international reputation as an outspoken critic of George W. Bush and Tony Blair's catastrophic ‘war on terror’, and the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Khan also repeatedly condemned the use of drones by western powers in Pakistan’s tribal areas, which border Afghanistan and were considered by the US to be a refuge for Taliban and al-Qaeda-linked militants.

But political success was painfully slow, as Imran Khan found it hard to convert his undoubted national popularity into parliamentary seats.

Debt crisis

The breakthrough only came this year - and the former sportsman was immediately forced to confront a dire national crisis thanks to mounting Pakistan debts.

His short-term strategy is to seek loans from Saudi and Chinese allies, and approach the IMF for what would be the 13th loan in Pakistan’s 70-year national history.

Over the long term, however, he aims to solve the problem by reigniting growth and tackling the corruption that has long dogged the country.

Khan spoke candidly about these issues, warning that Pakistan faces what he called ‘the worst debt crisis in our history”.

He told Middle East Eye that “unless we get either loans from friendly countries or the IMF, we won’t have enough foreign exchange to either service our debts or pay for our imports”.

He promised to crack down on money laundering saying that it was the bane of third world countries: “What happens is that the money’s looted by the ruling elite and then it’s siphoned off, laundered out of the country.”

Khan cannot be blamed for the massive debts inherited from previous governments. But he will most certainly be judged on how he confronts the problem.

Critics, however, accuse Khan of depending on support from the Pakistan military establishment, which has been accused of cracking down brutally on the free press and broadcasting media.

Protection for independent media

There are even fears for the future of Dawn, the newspaper set up by the founding figure of the Pakistan state, Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Last week the New York Times published a damning front page critique which concluded that “If Jinnah were alive today, he probably wouldn’t be able to write what he thought in the paper he founded.”

But Khan said he wanted to protect the independence of the media and changes were underway, mentioning new measures to provide funding for publications via government advertising regardless of their editorial positions.

“For the first time in Pakistan history government advertisements are given on a formula rather than on what the papers write,” he said. “Previously adverts were given on the number of pro-government articles.”

He also promised to introduce a Protection of Journalism Act, saying there is legislation to protect journalists in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the northern province where his party has been in power since 2013.

“Now we are going to do it all over Pakistan,” he said, adding that he owed his eventual political success to the country’s thriving media industry.

“I would never have succeeded in Pakistan if I did not have an independent media here, where I was able to put forward my views.”

Khan also told MEE that he was personally leading the way in belt tightening and austerity, having already sold off 80 cars and converted the large prime ministerial gardens into “a state-of-the-art postgraduate university.”

He strongly defended the controversial Chinese Pakistan Economic Corridor, linking western China to Pakistan and the port of Gwader on the Arabian Sea. Mr Khan said that it was a “great opportunity” which meant that “Pakistan can take off”.

It is 25 years since Imran Khan led his country to sporting triumph. Now he faces an even greater challenge putting Pakistan on the path to economic success and rebuilding its broken politics.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.