Who's next? Thousands of Palestinians face eviction after Khan al-Ahmar demolition

RAMALLAH, occupied West Bank – The Bedouin village of Khan al-Ahmar appears as little more than a collection of makeshift tin shacks and tents, nestled on a West Bank hill to the east of Jerusalem.

But during the past year its Palestinian residents have battled the Israeli authorities both through the courts and on the ground to prevent it from being demolished.

At time of writing, the security cabinet has decided to postpone demolition of the entire village – and forcible eviction of its some 200 residents - until further notice, although Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has vowed it will go ahead.

Khan al Ahmar will be evicted very soon, I shall not tell you when. We are preparing for it

- Benjamin Netanyahu, Israeli Prime Minister

On Monday, Netanyahu, who is facing political pressure at home, told a Likud meeting: “Khan al Ahmar will be evicted very soon, I shall not tell you when. We are preparing for it.”

The village has been under threat since 2009, although the government only renewed its commitment to demolish it a little more than a year ago.

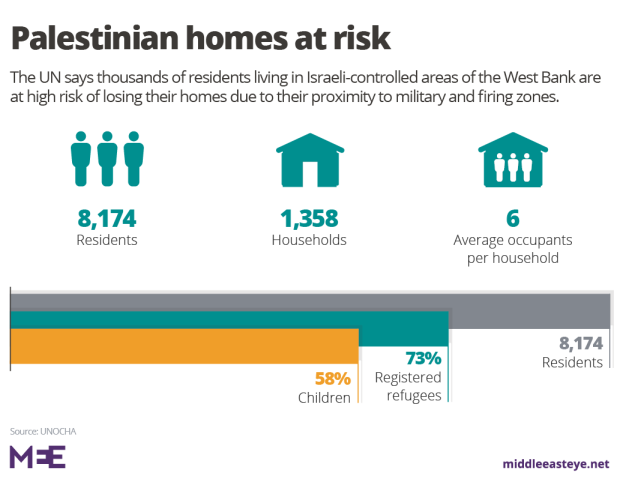

But the plans for Khan al-Ahmar are not arbitrary: at least 46 other Palestinian farming and shepherding communities, housing more than 8,000 people, are at high-risk of demolition and forcible transfer, according to the United Nations.

A campaign of confiscation

The communities all lie in Area C, a territory that comprises close to 64 percent of the occupied West Bank under control of the Israeli army, which is responsible for planning and zoning.

Designated as part of the 1995 Oslo II accords between Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), the region comprises the majority of the West Bank’s fertile land, water resources and minerals.It also includes all the Jewish-only settlements, illegal under international law, which the Israeli government has been building and funding since the military occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem in 1967.

But Area C has also witnessed a campaign of land confiscation, harassment and forcible transfer by the Israeli authorities against Palestinian communities.

According to Suhail Khalilieh, the head of the settlements monitoring department at ARIJ, a Palestinian NGO based in Bethlehem, the communities have not been given eviction orders ahead of demolition. But the Israeli army routinely demolishes structures essential for livelihoods within the villages, while also severely restricting the movement of residents.

Israel was meant to transfer control of the area to the Palestinian Authority within two years of Oslo, by 1997. Instead, it intensified its occupation and, critics say, made it harder for any handover to take place.

Indeed, since the first of the accords was signed in 1993, the Israeli population in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem has more than doubled: today stands at between 600,000 and 750,000, according to the UN.

Which areas are being targeted?

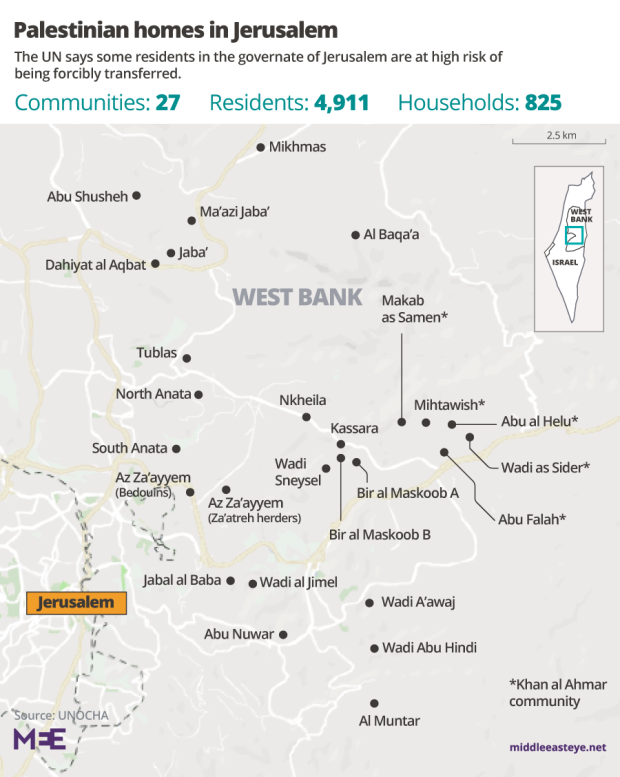

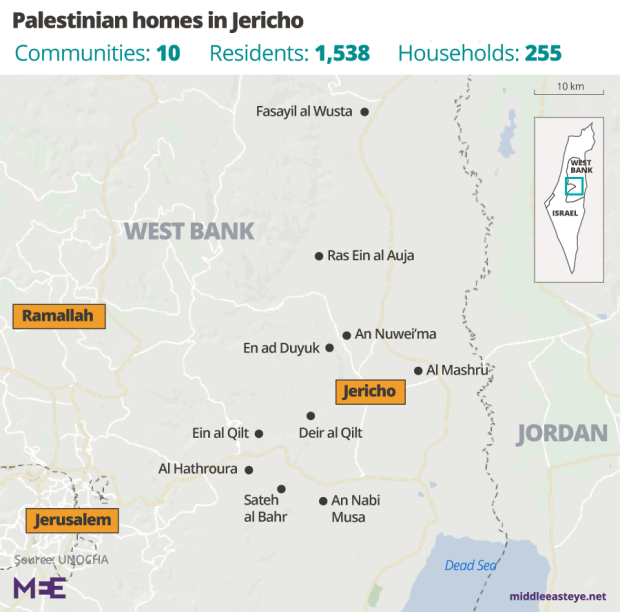

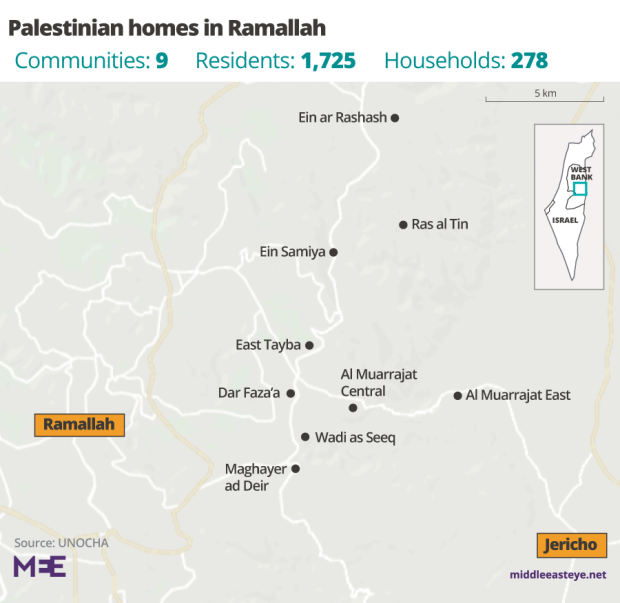

The Israeli army’s efforts are presently focused on three regions in Area C: the area in the Jerusalem governate that surrounds the West Bank settlement of Maale Adumim and which is close to Khan al-Ahmar; the part of the Jericho governate that includes the Jordan Valley; and the sections of the governate of Ramallah.

While the UN has not classified the communities in the South Hebron Hills as being at imminent risk, Israeli forces have also focused their efforts on that area in recent years.

The majority of the residents in these villages are refugees who were expelled from their original lands in the Negev desert after the ethnic cleansing of Palestine by Zionist militias in 1948.

Many are Bedouin, a semi-nomadic people, who have not been allowed to return. Instead, they are now internal refugees, concentrated in communities around Jerusalem, Jericho, Hebron and Bethlehem.But they are at constant risk of displacement again because of Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank since 1967, the launch of the settlement enterprise and the Israeli army’s takeover of large swathes of land for what it has described as military zones.

The Israeli army also severely restricts the expansion of Palestinian communities, refusing to connect them to water and power grids or pave roads to the villages. When residents build their own solar panels, install their own water tanks and pave their own roads, the Israeli army demolishes them.Khalilieh believes that the authorities target those communities because they are in “sparsely populated areas” and have no political power. “Israel sees them as large swaths of land not only for enlarging settlements but to also to use as military bases and training zones.”

It’s easy for Israel to target them. They have almost no chance of winning any kind of legal battle

Suhail Khalilieh, ARIJ

Many of the communities, he says, do not have the deeds to prove their ownership of the land, despite having lived there for decades.

“It’s easy for Israel to target them. They have almost no chance of winning any kind of legal battle.

"Most of these communities that Israel wants to seize are on public Palestinian land. Israel saw itself as the legitimate heir to these lands.”

No paperwork? That means no village

The Israel authorities say that all the villages under threat of demolition have been built without the necessary permits.

The Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) told MEE in a statement that it “operates in accordance with its authority to carry out enforcement against illegal activity in Area C, without distinguishing between the populations.

“Therefore, insofar as construction is carried out without a permit or planning regulation, the Civil Administration operates in accordance with its authority to implement the rule of law with regard to all illegal construction.”

But it is near impossible for Palestinians to obtain the required paperwork if they do not have permission: between 2010 and 2014, the Israeli army, which runs civil affairs in Area C, only approved 1.5 percent of applications submitted by Palestinians, rendering any other construction as “illegal” and at risk of demolition.The razing of these communities and the forcible transfer of their occupants are necessary if the Israeli state plans to maximise its settlements, most of which have been built entirely or partially on private Palestinian land.

As part of that plan, the authorities also hope to annex the major West Bank settlement bloc of Maale Adumim and surrounding settlements to the city of Jerusalem under the “Greater Jerusalem” bill.

It would add some 150,000 Israeli settlers to the population of Jerusalem, thereby ensure a Jewish majority in the city, a publicly stated goal of the Israeli government.

According to Khalilieh, the focus on evicting Palestinian communities surrounding Jerusalem is to “empty the area of Palestinians before annexing the settlement blocs to the city".“This is part of the geographic and demographic war. As much land and Israelis added to the city of Jerusalem with as few Palestinians as possible,” he added.

But under international law, the forcible displacement of an occupied civilian population – whether direct or indirect - constitutes a war crime.

Elizabeth Throssell, the spokesperson for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, says the conditions in which these communities live may leave them with “no choice but to leave”.

“This environment […] includes human rights violations such as forced evictions primarily as a result of demolitions in the context of an illegal and discriminatory planning regime, intimidation and harassment from government officials, security forces and settlers, exposure to military trainings, restriction on access to essential services, and impediments to humanitarian assistance,” Throssell told MEE.

Palestinians running out of space

The Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC) is a non-profit that aids Palestinian herders and farmers. It also supports communities at risk of eviction, helping residents register their lands, rehabilitating land, building infrastructure and providing veterinary services.

Aghsan Barghouthi, a press officer for the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC), says land in Area C is essential for Palestinians. “There is no longer space for development in Areas A and B," Barghouti told MEE.

Barghouthi said the campaign was a response to incitement by the Israeli army and settlers against the residents.

“It is our right to work these lands because they are Palestinian lands. Time has pardoned the Oslo accords – the agreement is no longer legal - but Israel continues to control our lands.

She said that settlers were continuing to attack farmers and their land daily, destroying more than 5,000 trees so far this year.

“Our duty is to return to the land. If we do not work the land with our own hands, the occupation will bulldoze us along with our fields.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.