Why Turkey’s plans for a safe zone in Syria are unlikely to materialise

Turkey’s slow-moving negotiations with the United States on cooperation in the alliance against the Islamic State received a mild jolt on Thursday when Ahmet Davutoglu, the Turkish prime minister, outlined proposals for a safe-zone in Syria to Al Jazeera’s Arabic service.

A safe-zone, accompanied by a no-fly zone, has been high on the list of the things which Turkey wants in exchange for cooperation against IS. Neither idea is actually new in principle. Opponents of the Assad government, including some in the US, have wanted them for several years, hoping that this would deliver a knock-out blow to Asad and put an end to hostilities.

The thinking was that safe zones would provide refuge for opponents of the Damascus government and that opposition forces could be organised, trained, equipped, and vetted on them. The emergence, on Syrian soil, of an embryonic alternative new administration might tilt support further in favour of the opposition and reverse the current fragmentation and regionalisation of Syria. A no-fly zone would provide protection for the population of the safe zone and help neutralise Assad’s main strategic advantage, his total superiority in the skies.

These plans did not proceed for two main reasons. Firstly, the Free Syrian Army failed dismally to live up to the military expectations of its backers and, as long as the opposition could not capture and hold a single Syrian province, the international legal implications of creating safe zones and no-fly zones put them out of the question. Secondly, Western governments were well aware that any such moves would be fiercely resisted by President Assad’s main backers, the Russians, and might lead to a serious international confrontation at a time of generally growing tensions.

In the spring of 2013 one of Syria’s 14 provinces did eventually fall to opposition forces - when the Al Nusra Front took Ar-Raqqa in the east. However, while its fall was indeed followed by the proclamation of a rival government, this happened in a way which the international opponents of Assad had not expected: Raqqa soon became capital of the Islamic State of Syria and the Levant (ISIL) now known as IS.

But Turkey’s desire for regime change in Syria was not abated. Its hopes of regional great power status in the Middle East are pinned to regime-change in Damascus and the emergence of a Sunni-led government there with close ties with Ankara. So Ankara continues to press the US for the twin aims of a safe-zone and a no-fly zone. If it can achieve them - without drawing in outside powers friendly to Assad, i.e. Russia and Iran - the days of his government in Damascus would probably be numbered. Aleppo, Syria’s second city, is only about 50 km south of the Turkish-Syrian border and would be the natural focal point from which a new political order in Syria might emerge.

There are two further reasons why Turkey urgently wants to see a safe-zone created in northern Syria. As a result of the war, it is sheltering over 1.5 million Syrian refugees and there is hardly a town in Turkey today where Syrian refugees, many of them outside camps and in fairly desperate conditions, cannot be seen. Though Turkish commentators accept that a good many refugees may never want to return to Syria and could stay permanently in the more prosperous conditions of Turkey, some of them at least could be housed in safe zones on Syrian soil, relieving the growing pressure.

Second, an international presence with a strong Turkish component in the zones would either curb or even eliminate the three autonomous Kurdish ‘cantons’ set up by the PYD, the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party, which hug the Turkish-Syrian border and are extensions of the PKK, Turkey’s revolutionary Kurdish movement.

These considerations may explain the map that accompanied Mr Davutoglu’s remarks to Al Jazeera on Thursday.

The map shows a thick swathe of territory stretching from al-Ladhiqiyah on the Mediterranean coast to Qamishli, near the border with Iraq. It would include the six major Syrian frontier towns, including Ain al-Arab also known as Kobane, where IS and Democratic Union Party (PYD) forces have been fighting each other since 15 September. Strikingly, Turkey does not propose that Tel Abyad, the frontier town which has been under IS control since mid-September, should be included in the Safe Zone. It is hard to see this as anything except a signal to IS that the zone would be directed against Assad and perhaps against also the PYD - who are vehemently opposed to the zone and what it would mean for them.

Turkey, however, insists that it sees the safe zone as primarily humanitarian.

“The buffer zone we intend would not be militarily defined, but would be a humanitarian safe zone, though one which would have military protection. It might be of varying depth in particular places,” Davutoglu said.

The key role would almost certainly be assigned to Idlib, the Syrian town across from the Turkish province of Antakya, where moderate Syrian opposition forces are strongest and could be strengthened further against Damascus.

Numerous obstacles, apart from those already mentioned, are also bristling in the way of anyone trying to set up such a zone.

A key sticking point would be the administration of these zones. Turkey continues to say its forces will not cross the border alone, a move which might spark military hostilities with the Damascus government. But even if these and other military obstacles could be overcome, the costs of running the zone would be unacceptable to the US.

General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, estimated recently that hundreds of US aircraft and costs of perhaps $1 bn a month would be needed for a Safe Zone in Syria, which was protected against both the Syrian air force and the IS. Davutoglu’s proposed safe zone looks to be larger and correspondingly even more expensive than what Dempsey was envisioning.

The benefits to Turkey of imposing such a zone in Syria, if one is ever created, would be tempting. But it would not be a zone which did much to counter the expansion of IS, especially in Iraq - which is the US’s main goal.

This would also probably wreck current attempts by the US and Iran to build up new dialogue and bridge decades’ worth of open hostility.

Until these critical problems can be resolved, we can expect Turkish-American bargaining essentially only over use of Incirlik air base against IS will continue.

Davutoglu perhaps revealed his safe zone map less as a piece of active diplomacy, than as an attempt to get Arab Sunni opinion firmly behind him.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

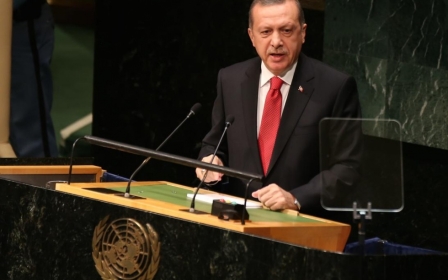

Photo Credit: Syrian refugees arrive in Turkey (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.