9/11 attacks: Why the 'war on terror' will not end

It took just two hours of mayhem and four hijacked planes on 11 September 2001 to arrive at the conclusion that America was at war with a new enemy of global reach.

That is what CNN said. That is also what progressive voices like the Guardian wrote the next day. To say anything less was regarded by public opinion on both sides of the Atlantic as effectively an act of treason.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Barbara Lee was the only congresswoman 20 years ago to stand up in the House of Representatives and plead with her colleagues not to give President George W Bush a blank cheque.

“Let’s just pause, just for a minute, and think through the implications of our actions today, so that this does not spiral out of control,” the US representative for California's ninth congressional district said to them days after the attacks.

She spoke in vain. Hers was the only no vote on the Authorisation for the Use of Military Force that the House approved by 420 to I. Lee received death threats, was called a traitor and accordingly assigned a Capitol police bodyguard.

Concealed truth

The horror of that day instantly mutated into a military fist which took more and more innocent lives. One 9/11 created hundreds more.

One of the resounding features of the 20-year so-called "war on terror" that followed was a concerted attempt by every government involved to conceal the truth about the casualties of this war; those many thousands of civilians lives every bit as innocent as the passengers on the four planes, the people in the Twin Towers and the first responders in Manhattan.

This continued until the last days of the US occupation of Afghanistan. When an Islamic State (IS) group suicide bomber blew himself up at the gates of Kabul airport, more than 170 people died. Virtually the entire media accepted - and still accepts - the story that those people died at the hands of the suicide bomber alone.

One BBC reporter did not, and interviewed the survivors. Secunder Kermani tweeted: “Many we spoke to, including eyewitnesses, said significant numbers of those killed were shot dead by US forces in the panic after the blast.” How many Afghans queuing to get into the airport were killed in the firefight that followed? No one followed his report up.

Similarly, the Pentagon maintained it had struck the right target when it destroyed, in a "defensive" military strike, a car packed with explosives and about to be driven, it alleged, towards the airport, by ISIS-K (the official affiliate of IS operating in Afghanistan). When it emerged that 10 members of one family, among them seven children, were killed in the blast, the Pentagon said they would have been killed by the secondary explosions.

A surviving brother said: "We are not ISIS or Daesh and this was a family home - where my brothers lived with their families.”

General Mark A Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that secondary blasts after the drone strike last Sunday supported the conclusion that the car contained explosives. But a subsequent initial analysis quoted by the New York Times is much less confident, saying it is only “possible to probable” that explosives were in the car.

Brown University’s Costs of War project estimated that up to one million people had lost their lives in the war on terror

In fact, every sinew has been strained over the past 20 years to hide the truth. This is no casualty of war - it is a deliberate policy of this war on terror to falsify the figures, such as work done by the US Department of Defense’s Office of Strategic Influence.

Brown University’s Costs of War project estimated that up to one million people had lost their lives in the war on terror. A recent report calculated that between 897,000 and 929,000 people - including at least 387,072 civilians - had been killed. But even these figures are thought to be a “vast undercount” of the toll of human life taken by wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen and elsewhere.

In 2015, the Physicians for Social Responsibility in the US estimated that more than one million people had been killed directly and indirectly in the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan alone.

Other figures from previous Brown University reports are no less horrifying, with an estimated 37 million people displaced. The war on terror, whose targets were never defined, whose countries were poor and Muslim and unable to defend themselves, devastated a whole region in West Asia.

Damning conclusions

Another barely commented-on report emerged in the welter of news and images of Afghan terror at the arrival of the Taliban in Kabul and the repeated messages that US President Joe Biden had betrayed the Afghans who had worked with - or, in the Taliban’s eyes, had collaborated with - the occupiers. This report was from an official US source: the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (Sigar). This inspector general had jurisdiction over all the programmes and operations paid for by US dollars over the last 20 years.

Its conclusions were damning. Each strategic aim contained its own undoing. The US wanted to root out corruption but also jumpstart the economy by injecting billions of dollars into it. It wanted to eliminate a culture of impunity but also maintain security, even if it meant empowering corrupt or predatory actors.

It wanted to give the Afghan security forces a competitive edge over the Taliban but also to limit the equipment and skills they could sustain after a US departure. It wanted to reduce the cultivation of the poppy, but do so without depriving farmers of their income. And so on. Strategy became mutually assured destruction.

The portrait that Sigar paints is of a colonial power that is no longer fit for purpose.

America did not have the intelligence, the local knowledge or the capability to govern what became a US dependency on the other side of the world. The outgoing Iranian foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, usefully described the inability of the West to read the Islamic world as "cognitive dissonance". It's a polite way of saying it was living in a different world.

After 20 years of occupation, you would have thought that western military intelligence would have had a better handle on the morale of the Afghan army that it had trained. To say, as it now does, that the Taliban was as surprised as anyone at how quickly it walked into Kabul, will not wash. It was the principal task of the US withdrawal to ensure that the state it left behind did not collapse.

No wonder the Afghan military, which numbered 300,000 “well-equipped and well-trained men”, melted away before the advance of an insurgent army 70,000 strong.

No accountability

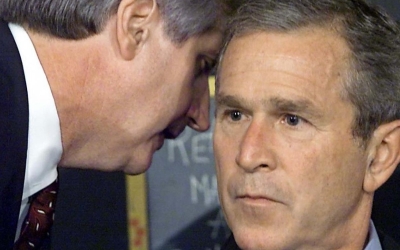

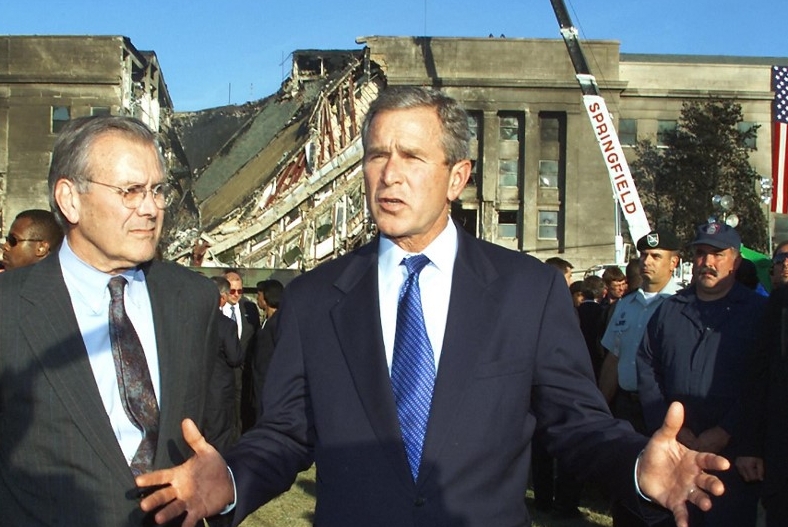

Another feature of the war on terror, apart from its length, the horrific casualties and the lies, is that no one responsible for it is has been held accountable or is willing to apologise for the decisions they took.

Not George W Bush, nor British Prime Minister Tony Blair, nor General David Petraeus or General Stanley McChrystal, the commander of the special forces, a man who once boasted he could "unpack democracy from the back of a Chinook".

McChrystal was fired after talking to Rolling Stone magazine - not for the damage he had done in Afghanistan, but for being disrespectful to President Barack Obama, then his commander in chief. Today McChrystal expresses no contrition. He told the Washington Post it was "too soon" to draw conclusions.

He conceded that the conflict “has had a very disappointing outcome”, but added: “I don’t think that means that necessarily many of the decisions made and the strategies pursued were wrong. I think in many cases they were the best strategy that could have been.”

McChrystal is a board member or adviser for at least 10 companies.

It is arrogance and wealth, not shame nor public humiliation, that characterises the lives of the architects of the war on terror today. Blair is treated as a wise elder statesman and his foundation is regularly quoted by the BBC. Far from being held accountable for their mistakes, these people market themselves as thought leaders. They continue to make considerable amounts of money.

Empires don’t die when their leaders hold up their hands. They die when they are no longer credible. Thus it is today. America’s loss of credibility under presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump means that the wounded beast of US power will continue no less viciously.

Impunity will continue

While Afghanistan itself is a lost cause for the West, the impunity given to air strikes on targets for which the US military is never held to account will continue.

So surely will Isis-K continue to operate, or whatever other al-Qaeda offshoot emerges. The invasion of Afghanistan 20 years ago did not palpably affect al-Qaeda’s operational ability to mount attacks on western targets. It simply displaced them. Nor is there much evidence of a direct operational link between IS and acts of terror in France, Britain or Germany, however hard French or British prosecutors try to establish one. Terrorism claimed in the name or under the banner of IS in Europe has become largely home-grown.

Empires don’t die when their leaders hold up their hands. They die when they are no longer credible. Thus it is today

Osama bin Laden continued in business for a full decade after the invasion of Afghanistan, nestling undercover in an army town in Pakistan. Nor it did prevent Abu Musab al-Zarqawi from emerging as his even more violent and sectarian successor.

It was not just the fact that the war on terror spawned more terrorists than it killed. It was that terror became the standard and accepted tool of everyone involved, not least the operators of drones.

The saddest epitaph of 20 years of fruitless war and destruction is that no one appears to have learned from it.

Few voices have been raised about the aid a ravaged and devastated Afghanistan will need. It will shortly run out of food, as well as money. And yet western leaders are teetering on the verge of treating the “Islamist” Taliban in the same way as it treated the Islamic Republic of Iran. When fighting stops in the war on terror, "peace" comes in the form of sanctions. The European Union has said it will not recognise the government of Afghanistan and the Taliban will continue to be on the US's list of terrorist organisations.

The first move the Biden administration made was to block access to $9.5bn in international reserve funds and pressure the International Monetary Fund to suspend the distribution of more than $400m in currency reserves. It says it needs leverage, but very soon aid must surely be given to some 30 million Afghans.

Repeating the same mistakes

Almost no one is saying that by walking away from Afghanistan, we are in danger of repeating the same mistakes we made in the 1990s.

“Mark my words,” Pakistan’s national security adviser Moeed Yusuf told the Times, “if the mistakes of the nineties are made again and Afghanistan abandoned, the outcome will be absolutely the same - a security vacuum filled by undesirable elements who will threaten everyone, Pakistan and the West.”

The war on terror was not lost to a defined enemy with superior skills. It was a massive own goal. It was designed as the ultimate expression of world leadership, of the technological and moral superiority of a civilisation that behaved as if it was the sole guardian of democratic values, and thus morally entitled to police the world. The collapse of the war on terror is a fitting epitaph to the conclusion that everyone in the West drew when the Soviet Union collapsed - that one side had won. What does "victory" look like now?

We did not “cement democracy”, as one New York Times commentator put it, by pushing the borders of Nato eastwards. We simply pushed the line of confrontation eastwards. We have repeated this mistake repeatedly over the last 20 years.

We have yet to re-examine the concept of world leadership, let alone collectivise it. In China, with Russia as its junior partner, the American century will not now be replaced with something superior.

If the lessons of this fiasco, paid for with the blood of millions, are to be learned, it should lead to the abandonment of the 19th-century talk of spheres of influence, or the colonial mentality of a clash of civilisations and values. It's simply too late for that, however much Americans believe in and practise their own exceptionalism.

From the end of the Soviet Union until now, America inherited at least three populations in the countries that either collapsed or they invaded - Russia, Afghanistan and Iraq; populations which were overwhelmingly pro-western but which the US turned into either tacitly or overtly hostile nations.

Iraq will be the next country to kick out US soldiers.

In all three zones where it was free to do what it wanted, America defeated itself. The Taliban, al-Qaeda and IS were the catalysts of its collapse.

Afghanistan is over. But until this lesson is learned, the war on terror surely lives on.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.