Afghanistan: The Taliban's punishment of women is an act of desperation

Two weeks before the start of the New Year, the ruling Taliban took some highly controversial steps in Afghanistan, inviting huge reactions from the Afghan diaspora.

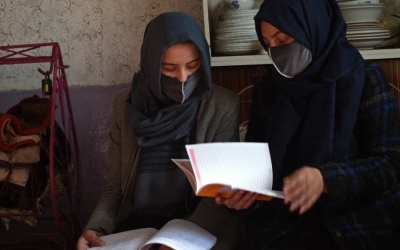

Hitting the education sector with a double slap, it banned higher education for women and tightened restrictions on schools for girls above the sixth grade. Even private schools which resisted the Taliban’s restrictions in the country’s northern provinces were also forced to shut down.

Scores of NGOs have suspended their operations in areas hit by severe food shortages, exacerbated by a continuous drought

This made Afghanistan the only country in the world where education is a crime, a situation requiring analysis including a security perspective to understand this oppression holistically.

On 24 December, the Taliban dropped another bombshell, issuing new orders telling international NGOs to stop their female staff from working because they were not respecting the militia’s dress codes.

This directive has effectively halted almost all developmental and much-needed relief works in Afghanistan, where people are struggling to survive a four-decade-long war by eking out a meagre living. In addition, over six million Afghans have been displaced.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

As a protest, scores of NGOs have suspended their operations in areas hit by severe food shortages, exacerbated by a continuous drought.

Punishing Afghans

So, just why is the Taliban so vicious? Is it seeking revenge on the progressive values of the contemporary world or does it just want to punish Afghans basically for nothing?

Taught in segregated seminaries that were set up in cross-border areas after the US-sponsored "jihad" in the 1980s, or raised as refugees in the urban ghettoes and slums of Pakistan, the Taliban’s ideology does not represent the religiously and culturally diverse Afghan nation. Yet, they seem hell-bent on imposing themselves on a country of 40 million people, forcing women to the brink of gender apartheid.

Ever since the Taliban was invited by the US to take over Kabul in August 2021, this embrace was expected to end the last 20 years of war that started in 2001 with the US dismantling the Taliban’s first rule for protecting Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaida chief.

Contrary to expectations, however, the Taliban’s second rule, with its dismal record on rights and freedoms, as well as a failure to allow inclusive political government, has made a mockery of US claims that it had negotiated peace with a "reformed Taliban" - who would accept women as shareholders in society.

To add insult to injury, progressive Afghan values were systematically targeted. Initially, all girls were stopped from going to their educational institutions, an order that was later revised for girls' primary and secondary education.

Eighty percent of secondary schoolgirls (850,000 out of 1.1 million in 2021) could not attend classes due to this ban, according to a UN Gender Alert.

On 7 May 2022, a new directive was issued, stopping women from leaving home if they didn't observe a particular dress code or were not accompanied by a close male relative.

Over 300 media outlets were closed down, leaving over 10,000 workers jobless, including 5,000 male and female journalists. The Taliban’s restrictions on freedom of expression also forced over 2,000 journalists to flee the country, some still in hiding in Pakistan and Iran.

Diaspora's fury

Amid this turmoil, social media is the only contact between a burgeoning Afghan diaspora and the rest of the country’s population being held hostage by the Taliban’s orthodox rule.

The ban on girls’ education has become the latest subject of the diaspora's fury. Social media is abuzz with trends (#letAfghanGirlslearn) and viral condemnations. Video clips are doing the rounds in which male students are shown quitting examination halls and teachers leaving their jobs in solidarity with their female colleagues.

In some cases, protesters were beaten by the Taliban. In another, a daring female solo protester, with a placard in her hand reading “iqra”, the Arabic word for “read”, faced the trigger-happy militia’s soldiers in front of a military compound.

One female medical student reportedly committed suicide. A male TV anchor, while announcing the ban, broke down. Another emotional man tore away his transcripts in his media interview. While these reactions are instantaneous, the ban is not. This charged situation is an outcome of mounting challenges the Taliban has started to face.

Zawahiri’s death raised many questions. Who gave on-the-ground intelligence for the US attack? Is Kabul safe anymore?

Ever since signing a peace deal with the US in Qatar in 2020, the Taliban hoped for formal recognition. But not a single country has recognised them. In July last year, this mistrust reached new heights. The Taliban received their first major blow when al-Qaida’s top leader, Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri, a mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, was killed in a US drone strike in Kabul’s high-security zone. He lived with top Taliban leaders as a "state guest" in a "safe house".

Zawahiri’s death raised many questions. Who gave on-the-ground intelligence for the US attack? Is Kabul safe anymore? Reportedly, even top Taliban leaders left the capital city for fear of more attacks.

Though otherwise remaining tight-lipped, the Taliban's spokesman, Suhail Shaheen, denied having any knowledge about Zawahiri’s entering and living in Kabul. Yet the Taliban knew that, after the incident, no country was going to recognise it; a factor which partially increased its desperation and which has seen it sadistically using Afghans, and especially women, as a punch bag to test the world's raw nerves.

Divisions within Taliban

Another side of the Taliban’s challenge is existential. Zawahiri’s death has confirmed the rumours that there are widening gaps in its ranks.

From the start, the militia was divided into two main groups: one led by its deputy prime minister, Abdul Ghani Baradar, called the Kandahari group, which is entrenched in Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second city, near Pakistan’s southern border; the other led by its hardline interior minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani, with links to the Pakistan military.

The Haqqani group controls Kabul and the provinces leading to Pakistan’s northwestern border and beyond, a strategic advantage it availed during fighting against the US-led Nato forces.

This division seems dormant, but the mutual tensions from time to time weaken the Taliban's grip over the country. The barometer of this division is their rival militant group, the Islamic State Khorasan (IS-K). The IS-K’s numbers doubled in 2022, spreading its operations to all of the country’s 34 provinces, targeting with precision the Taliban's interests, including attacks on Chinese, Russian and Pakistani missions in Kabul.

Without admitting the presence of the IS-K, the Taliban, however, understands that this challenge could not arise without defections in its own ranks. This rising threat can make the IS-K a site of convergence for anti-Taliban groups, including resistance in the country’s northern parts, and especially the Panjshir Valley.

Unleashing the current oppression against women, therefore, also reveals the Taliban leaders’ efforts to make their foot soldiers realise that their ideology of implementing their own violent brand of sharia is intact, a system in which women are forced to stay at home.

On the whole, the crisis of the Taliban’s Afghanistan reveals the contradiction of the global powers. While the US cut a deal with the militia, hoping it would lay down arms to rule Afghanistan politically, it ignored the fact that the Taliban’s strength rests in its al-Qaida-style extremism.

It is not in its DNA to relinquish what it has achieved through its visceral acts of terror. So, the issue of women's rights and freedoms is part of the larger security context within which the Taliban emerged to become such a powerful force.

The solution to the ban on girls’ education in Afghanistan, therefore, does not rest in reconciliation with the Taliban.

Rather, it rests in showing zero tolerance for terrorism and militancy in the region, including discouraging regional stakeholders, especially Pakistan, China and Qatar, to avoid any kind of relationship with the Taliban unless the movement changes its discriminatory approach towards women.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.