Algeria and Sudan: The revolutionary dilemma

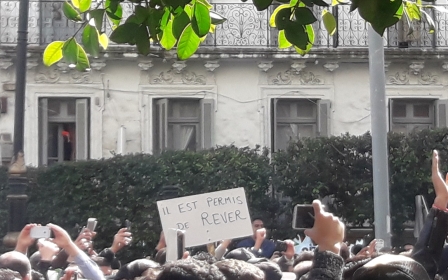

The mass demonstrations that have been unfolding for months in Algeria and Sudan have renewed hopes for democratisation in the wake of the 2011 uprisings.

Change will undoubtedly take place, as it has in all other countries that have experienced protracted protests - but whether either country will experience a democratic transition is more open to question.

Should this occur, many protesters will be profoundly dissatisfied. Democratic transitions do not produce swift, radical change, but reforms forged, usually slowly, through compromise.

Radical change only occurs when a faction manages to impose its will on the rest, often through violence. Profound revolutions are never peaceful, and they usually lead not to democracy, but to new forms of authoritarianism.

Change can take place through peaceful, democratic means, but it requires a lot of compromise

It is difficult to generalise about what the protesters want in Algeria and Sudan, or in any of the earlier Arab uprisings, because protesters are not a homogeneous block.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The strength of the Arab uprisings is that they have been, and continue to be, genuine grassroots movements - but this is also their weakness, because at some point, street protests must turn into a plan of action, which requires leadership and organisation.

It is clear from the slogans that at a minimum, protesters want the removal of the old leadership - the regime, rather than just a few people at the top - and the formation of a civilian government. They also want redress for socioeconomic grievances.

Such demands are understandable, even admirable. Unfortunately, they are unlikely to be attained through a peaceful process - one without violence and the violation of the human rights of many.

Elite resistance

Radical, revolutionary reforms are bound to cause strong resistance among those threatened by the changes. Powerful elites, particularly in the military and security services, do not surrender without a fight.

In Egypt, when the victory by Islamists threatened its position, the military elite simply seized control.

When Islamists tried to cling to power after the July 2013 coup, the outcome was bloody repression and the imposition of the most militarised regime Egypt has ever had.

In Algeria in the 1990s, the Islamists’ refusal to renounce their election victory and give in to the military resulted in a decade of brutal conflict.

Transitions that follow a democratic path, through dialogue among all sides and eventually elections, are possible - but they have their own costs, in that they only produce limited change.

There are many studies of peaceful democratic transitions in Latin America, but the most interesting example for the Arab region is that of Tunisia, the country generally considered to have come closest to democracy after 2011.

Tunisia has avoided violence, repression and military intervention. It has formed all post-2011 governments through elections and negotiations.

But it is also a country where the youth who played a crucial role in the street movement in 2010 and 2011 are thoroughly disenchanted by the limited change, refusing to participate in elections they do not expect to bring about the needed changes.

It is also a country that has seen a disproportionate number of radicalised youth go to join the Islamic State. Its transitional justice process - the attempt to throw clarity on the misdeeds of the old regime - has been limited and short-lived.

In the end, many people close to the old regime have been rehabilitated, keeping their money and reentering the political process.

A hard lesson

Tunisia illustrates the costs of a process of transition that unfolds within the limits of a democratic process. To be sure, not everything that happened was unavoidable. The Truth and Dignity Commission could have continued its work for a longer time and with more energy, providing greater clarity.

The reconciliation law that rehabilitated corrupt members of the old regime could have been less lenient. But a deep purge of those associated with the old regime would have required strong measures incompatible with a democratic process, planting the seeds of a new authoritarianism.

This is the hard lesson from the outcome of the 2011 uprisings for countries such as Algeria and Sudan: change can take place through peaceful, democratic means, but it requires a lot of compromise, and thus will be incomplete and fall short of what many hoped for.

Attempts to bring about more radical changes, by punishing and excluding a large part of the old elite, are not possible by democratic means, because such efforts elicit a strong reaction - a counterrevolution - leading to violence and repression.

The question for those seeking change is whether they want democratic change or radical change, because the two are incompatible.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.