Algeria's women: Unsung heroes of the revolution

As celebrations take place to mark International Women's Day, Algerian women are also set to make their presence and demands for liberation known, as weekly anti-regime protests continue.

It has been a year since Algerians took to the streets in cities, towns and villages, first to oppose then-president Abdelaziz Bouteflika's desire for a fifth term, and later to oppose the regime as a whole.

Since then, much has been won: Bouteflika's resignation, the postponement of the national election, the delegitimisation of the rescheduled vote through a coordinated national boycott, the release of countless political prisoners, and the imprisonment of leading regime figures.

Opposing the regime

Recent weeks have seen significant national unity and mass organisation in the continued fight against the military regime, which has ruled Algeria since the people gained their independence from France in 1962. Last month also marked the anniversary of the assassination of Nabila Djahnine, a women's rights activist killed during the civil war in the 1990s.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Djahnine fought for the rights of Algerian women and was an outspoken critic of the regime and family-code laws, which effectively rendered women second-class citizens, financially and socially dependent on their husbands or fathers.

She inspired many to oppose the regime and denounced violence against women. The struggle she waged decades ago continues to this day.

You could see the roots of her love, admiration and drive for the people on the ground, in their masses

Algerian women were, in so many ways, betrayed in the aftermath of the revolution and independence, as the regime consolidated its power across every institution.

The demands and critique of leading female activists were pushed aside and denounced as being counter to the "national interest". The contributions of former female revolutionaries were, at best, selectively taught in schools, often consigned to obscurity in public national archives.

Outside of some oral and written accounts, along with videos of speeches that have resurfaced thanks to the internet, you would hardly hear of the likes of freedom fighters such as Djamila Bouhired. But activists like her - who were tortured, imprisoned and faced the death sentence for opposing French colonialism - keep the fire of the liberation struggle alive in the collective memory of the people.

Today, Bouhired tours the country as part of the Hirak movement, rallying for more protests, disruption of the status quo and recognition that equality and justice have yet to be delivered to the Algerian people - especially women.

The right side of history

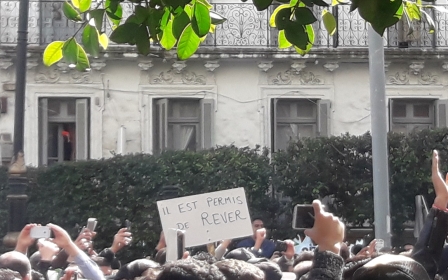

With the one-year anniversary of the Hirak protests approaching, I recently joined the weekly Friday demonstrations in Algiers. I sat alongside former National Liberation Front (FLN) militant Louisette Ighilahriz, while waiting for people to assemble for the march. The 83-year-old has joined the Hirak every week since 22 February 2019, "so that le pouvoir [the power] knows that it has betrayed the people; it has betrayed our fight," she told me.

As more and more people assembled around us to kiss her cheeks, take a photo, or simply tell her of the strength and inspiration that she provides, Ighilahriz appeared overjoyed to be among her people, yet again on the right side of history.

Her sharp political senses still intact, she dutifully checked the messages on any banner anyone wished to place in her hands for a photo. She would not have anyone put words in her mouth that she did not stand by.

The Algerian state has already rewritten so much, forcing a repressive and corrupt regime to rule with the false justification that it honoured the hundreds of thousands of martyrs of Algeria's war of liberation.

The image was a powerful one. You could see the roots of her love, admiration and drive for the people on the ground, in their masses. It was a brief moment of reclaiming the real revolutionary memory of Algeria - the one that lives, and struggles, on.

I asked Ighilahriz what she would want communicated internationally to those who wish to support the Algerian struggle today. She answered: "We need your solidarity, to speak, to shout, to make the demands of the Algerian people known around the world."

'Speak without stopping'

Writer Assia Djebar, one of the most important voices for Algerian women, once wrote that there is only one way to free Algerian women: "Speak, speak without stopping, of yesterday and today" in order to look out "beyond the walls and the prisons".

Indeed, the women of the Hirak, often found leading the demonstrations, are fighting to tear down all the walls erected around them.

When the regime attempts to imprison them for daring to seek freedom - as was the case with activists Samira Messouci, Nour el-Houda Dahmani and Fatiha Belaifa, to name but a few - it only strengthens their conviction to fight harder. Messouci, who was becoming a growing threat through her political sharpness, powerful speeches and mobilising abilities, was released after serving six months in prison - and returned to the streets immediately.

There are also other, different heroes of the Algerian women's struggle. Just a few days before International Women's Day, my aunt Nejma passed away. Unknowingly, and certainly unintentionally, she was my feminist hero.

Like so many Algerian women, her contributions were hardly recognised while she was alive; if anything, they were recounted as a flaw. To me, she represents the Algerian women who have spent much of their lives fighting against a system built to silence them through violence and misogynistic laws.

She lost her father at a young age and found herself responsible for an illiterate mother, who had been married when she was still just a child, as well as her brothers and sisters.

She took on the role of providing for them, taking her father's place and having the door constantly slammed in her face, facing rejection at every turn. She was pushed away with the ubiquitous, "Madame, this is simply not possible" to all financial or legal issues she attempted to resolve.

Shining bright

I never once witnessed her accept defeat. I don’t think she even understood the meaning of "knowing her place". Growing up, I'd hear male cousins and uncles joke that she wasn't really a woman.

She knew that her demands for a functioning welfare state, access to healthcare, well-funded education and a non-discriminatory inheritance law were all basic rights that should not require impossible strength, endless battles and even threats to freedom.

She took these battles on, every day, not because she was a feminist activist - she wouldn't have liked the term - but because she wanted a decent life for herself, her sisters and her nieces.

Her battle is that of the millions of Algerian women in the streets, in the cells of the regime, and in the workplaces of Algiers, Constantine and Oran

The Algerian women marching today similarly refuse to accept that, in a country rich with oil and natural gas, these demands should be anything but basic demands, rather than huge concessions.

No matter what my aunt achieved - often with much personal sacrifice - she continued to be belittled by the men around her.

None of it mattered to her in the end; she expected and regretted nothing. She was Nejma ("star" in Arabic), and she shone brighter than all those around her who were complicit in a system stacked against women.

Her battle is that of the millions of Algerian women in the streets, in the cells of the regime, and in the workplaces of Algiers, Constantine and Oran - but also of Marseille, Paris and Lyon. Their struggle is daily, ferocious and unrelenting. And they know that this time it is, in the words of the ubiquitous chant, "revolution until victory".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.