Bad neighbours make good fences

Israel is a small and heavily populated country that surrounded itself by fences and walls. There is very little open space between communities. It seems as if one town ends where the next one begins. So when a wall, a barrier or a fence is built, it is built on top of houses, yards and fields. Much has been written about the Apartheid Wall which Israel began building in 2002. It was built on Palestinian land and it separates Israel and the Palestinian West Bank. The separation wall includes fences and walls which are more than 700 kilometres long, while the border itself is only 320 kilometres. This massive barrier is the most expensive building project in Israel’s history. A similar 55-kilometer barrier separates Israel from the people of Gaza.

The barriers separating the citizens of Israel from the Palestinians in the occupied territories are well-known. But when we look inside Israel itself, we find separation between Jewish and Palestinian citizens as well. The two most central forms of separation are the living arrangements and the schools. Separation influences us daily and constructs the way we live and think. The most integrated sites are hospitals and low-paying work places, where interaction between the two national groups does take place. There are structural barriers and there are the mental, unseen barriers - those that are not created by laws or planning committees, but by popular Jewish-Israeli culture.

For example, Palestinian citizens find it extremely difficult to rent apartments in Jewish cities (where there are more job opportunities and higher educational institutions). There is the language barrier as most Israeli Jews do not speak Arabic. Palestinian citizens often refrain from speaking their own language in the public sphere for fear of being regarded as a security threat and of being harassed. Their fear is not a subjective interpretation of daily experience. Since 2000, the Israeli police killed 16 times more Palestinian than Jewish citizens of Israel. Statistically, when considering the relative size of the Palestinian minority, this makes the situation incomparably more severe than in the United States where police discrimination against blacks has led to demonstrations across the country.

One mechanism of separation is both physical and mental.

In Israel there are many gated communities - all of them Jewish. It is interesting how fences and electric gates are conceived as a good way to live your life. We can see fences around kibbutzim (cooperative farming communities), around middle class suburbs and around wealthy housing projects in the big cities. What all these people have in common is that they close themselves off from an undefined evil, mostly from thieves.

But there are three Jewish communities which built concrete walls and barriers and clearly declared that they were erected to separate between Jews and Arabs. All three were built between 1999-2002, just before the Israeli government began constructing the Apartheid Wall between Israel and the Palestinian territories. These barriers were officially built as acoustic walls, as if to keep out Arab noise.

Unofficially, they are there to protect against crime and devaluation of real estate. They are based on the deep-seated assumption that Palestinian neighbours are a threat. Most of all, these walls symbolise the desire to live in a “clean” environment. Of course, the barriers are not fool-proof. Even if acoustics were the real concern, the muezzin can still be heard on the other side calling to prayer five times a day.

One apartheid barrier was erected between a Jewish neighbourhood and a Palestinian neighbourhood in the city of Ramla, which lies roughly half-way between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. The second was built between the ultra-rich community of Caesarea (population 4,900, including Prime Minister Netanyahu) and the Palestinian village of Jisr az-Zarqa (with a population of 13,500 in the lowest socio-economic level of the country-1 out of 10). I recently paid a visit to the third wall, in Lid.

Lid is referred to as a mixed city. Mixed cities were Palestinian cities until 1948, when the Palestinian residents were expelled and Jewish immigrants were brought in. For example, in the city of Lid (Lod in Hebrew) there are 74,000 residents with a 27 percent Palestinian minority. The original Palestinian community that remained after the war in 1948 was joined by three Palestinian groups: internal refugees, Bedouin who were driven off their land and legally resettled in the city and Palestinians who collaborated with the Israeli armed forces and were settled there by the government.

These forced resettlements had a devastating effect on the Palestinian community which had to rebuild itself while it struggled as an oppressed minority in the city. Lid, with its Jewish and Palestinian residents, is in a low socio-economic rank (4 out of 10), but its Jewish neighbours are not.

On the western outskirts of the city, bordering the Bedouin neighbourhood of Pardes Snir, is the wealthy and spacious farming community of Nir Zvi. It sits on the land of what until 1948 was the Palestinian village of Sarafand Amar. Driving through Nir Zvi is easy. There is no guard during the day and everything is peaceful and neat. At the end of the road, there is a big field and at the end of that field a four-metre high concrete wall cuts off the view for one-and-a-half kilometres. The government put it up at the request of the Jewish residents. It does not actually prevent people from entering their community. It is more of a statement and a declaration.

Winston Churchill said that first we shape our buildings and then the buildings start to shape us. The concrete wall is a good symbol of the siege mentality that the Israeli Jews created for themselves in the area. One of the most common phrases Israelis use to describe life here is that “we live in a tough neighbourhood” meaning the Middle East. “Since everyone around us wants to kill us, we need to be strong and build high walls.”

Driving through the Palestinian neighbourhood on the other side of the wall is a more difficult experience. The roads are bad. Potholes make it hard to move and there is no sign of municipal investment or care. Children play in the mud and the wall is in your face. It is not far off in the horizon as it is for people on the other side. People sit in their homes facing concrete. I approached a man who was standing by the wall looking after his children as they played with marbles and I asked him what he thought of the wall. “Unnecessary” was all he said. As I travelled along the wall, I heard this word again and again. Most of the Palestinian residents are done being angry or humiliated. Fifteen years ago a regional planning committee decided to finally address Pardes Snir’s basic infrastructure needs with a development plan. The plan required regional approval. The Jewish neighbours jumped on the opportunity to condition their approval on the construction of a wall. Well, the wall has been there for some time, but Pardes Snir’s roads, sewage and playgrounds are yet to come. Last year someone came with a bulldozer and tore down a big chunk of the wall. Urban legend says that the municipality sent a crew to fix the gap, but they were scared off by the residents and never came back. That hole in the wall is the most encouraging thing that I saw in Pardes Snir.

There is an enormous economic gap between Jews and Palestinians in Israel. Palestinian citizens’ average income is 32 percent lower than that of the Jews. As renowned author and academic, Edward Said taught us, in order to define one culture as superior, we need to create a culture that will be inferior. The Orient constructs the West. In this case, the Jewish citizens’ self-perception is that of law-abiding citizens who work hard to make a living and build their homes according to city plans. Liberals tend to attribute their wealth and good fortune to their hard work. The Jewish citizens’ identity never includes the fact that most of the land upon which they sit has been stolen.

The Palestinian neighbours on the other side of the wall are their mirror vision. They are seen as criminals and as trespassers who built their homes with no regard for city plans and regulations. The history of the land is never part of the equation. Whatever way we look at it - through the national or the economic perspective - these mental and concrete constructions are what we need to destroy.

-Michal Zak is a political educator, an expert in Jewish-Palestinian dialogue and a resident of the Palestinian-Jewish community of Wahat al Salam-Neve Shalom in Israel.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

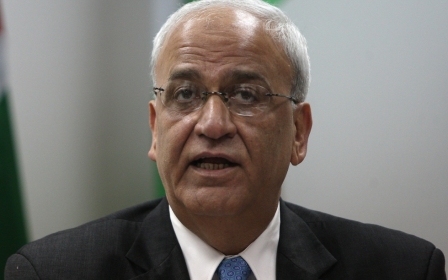

Photo Credit: Walls that can come up, can also come down (MEE / Oren Ziv)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.