The Balfour Declaration: A study in British duplicity

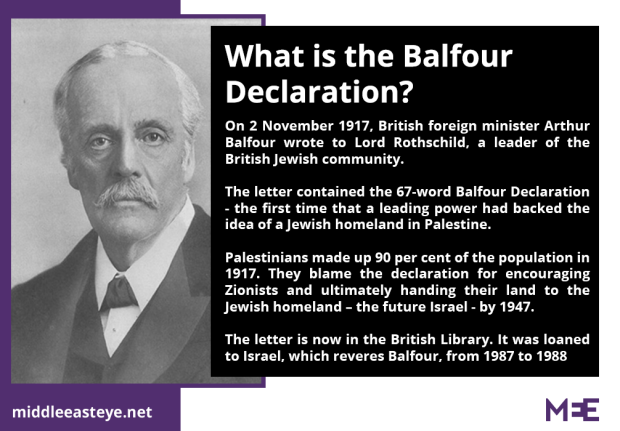

The Balfour Declaration, issued on 2 November 1917, was a short document which changed the course of history. It committed the British government to support the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine, provided nothing was done "to prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine".

At that time, the Jews constituted 10 percent of the population of Palestine: 60,000 Jews and just over 600,000 Arabs. Yet Britain chose to recognise the right to national self-determination of the tiny minority and to flatly deny it to the undisputed majority. In the words of the Jewish writer Arthur Koestler: here was one nation promising another nation the land of a third nation.

Britain's rulers, like the Bourbon kings of France, have apparently learnt nothing and forgotten nothing in the intervening 100 years

Some contemporary accounts presented the Balfour Declaration as a selfless gesture and even as a noble Christian project to help an ancient people reconstitute its national life in its ancestral homeland. These accounts spring from the biblical romanticism of some British officials and their sympathy for the plight of the Jews of Eastern Europe.

Subsequent scholarship suggests that the main motive for issuing the declaration was cold calculation of British imperial interests. It was believed, wrongly as it turned out, that Britain's interests would best be served by an alliance with the Zionist movement in Palestine.

Palestine controlled the British Empire's lines of communications to the Far East. France, Britain's main ally in the war against Germany, was also a rival for influence in Palestine.Under the secret Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916, the two countries divided up the Middle East into zones of influence but compromised on an international administration for Palestine. By helping the Zionists to take over Palestine, the British hoped to secure a dominant presence in the area and to exclude the French. The French called the British "Perfidious Albion". The Balfour Declaration was a prime example of this perennial perfidy.

Balfour's main victims

The main victims of the Balfour Declaration, however, were not the French but the Arabs of Palestine. The declaration was a classic European colonial document cobbled together by a small group of men with a thoroughly colonial mind-set. It was formulated in total disregard for the political rights of the majority of the indigenous population.

Foreign secretary Arthur Balfour made no effort to disguise his contempt for the Arabs.

"Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad," he wrote in 1922, was "rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs and future hopes of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land." There could hardly be a more striking illustration of what Edward Said called "the moral epistemology of imperialism".

Balfour was just a languid English aristocrat. The real driving force behind the declaration was not Balfour but David Lloyd George, the fiery Welsh radical who headed the government. In foreign policy, Lloyd George was an old-fashioned British imperialist and a land-grabber. His support for Zionism, however, was based not on a sound assessment of British interests but on ignorance: he admired the Jews but he also feared them and he failed to grasp that the Zionists were a minority within a minority.

In short, Britain's wartime support for Zionism was rooted in an arrogant colonial attitude towards the Arabs and a misconception about the global power of the Jews.

A dual obligation

Britain compounded its original mistake by writing the terms of the Balfour Declaration into the League of Nations' mandate for Palestine. What had been a mere promise by one great power to a minor ally now became a legally binding international instrument.

The real question to be asked is: did this immoral policy yield for Britain any concrete rewards?

To be more precise, Britain as the mandatory power assumed a dual obligation: to help the Jews build a national home in the whole of mandatory Palestine and, at the same time, to protect the civil and religious rights of the Arabs. Britain fulfilled the first obligation, but failed to honour even this paltry second one.

That Britain was guilty of duplicity and double-dealing is hardly open to question. So the real question to be asked is: did this immoral policy yield for Britain any concrete rewards? My own answer to this question is that it did not.

The Balfour Declaration was a millstone round Britain's neck from the beginning of the mandate until it reached its inglorious end in May 1948.

The Zionists claimed that everything Britain did for them in the inter-war period fell short of the original promise. They argued that the declaration implied support of an independent Jewish state; British officials retorted that they had only promised a national home, which is not the same thing as a state. In the meantime, Britain incurred the ill-will not only of the Palestinians but of millions of Arabs and Muslims round the world.

With the benefit of hindsight, the Balfour Declaration would appear to be a colossal strategic blunder.

The end result was to enable the Zionist takeover of Palestine, a takeover that continues to this day in the form of illegal but relentless settlement expansion on the West Bank at the expense of the Palestinians.

Entrenched mindset

Given this historical record, one might expect British leaders to hang their head in shame and disavow this toxic legacy of their colonialist past. But the last three British prime ministers of both main political parties - Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, and David Cameron - have all displayed staunch support for Israel and utter indifference to Palestinian rights.

Theresa May, the present prime minister, is one of the most pro-Israel leaders in Europe. In a December 2016 speech to the Conservative Friends of Israel, which includes over 80 percent of Tory MPs and the entire cabinet, she hailed Israel as "a remarkable country" and "a beacon of tolerance".

Rubbing salt in Palestinian wounds, she called the Balfour Declaration "one of the most important letters in history," and she promised to celebrate it on the anniversary.

The Balfour Declaration is an historic statement for which HMG does not intend to apologise. We are proud of our role in creating the state of Israel.

The declaration was written in a world of competing imperial powers, in the midst of the First World War and in the twilight of the Ottoman Empire. In that context, establishing a homeland for the Jewish people in the land to which they had such strong historical and religious ties was the right and moral thing to do, particularly against the background of centuries of persecution.

Much has happened since 1917. We recognise that the declaration should have called for the protection of political rights of the non-Jewish communities in Palestine, particularly their right to self-determination. However, the important thing now is to look forward and establish security and justice for both Israelis and Palestinians through a lasting peace.

It would appear that, despite the passage of a century, the colonial mind-set of the British political elite is still deeply entrenched. Contemporary British leaders, like their World War One predecessors, still refer to the Arabs as "the non-Jewish communities in Palestine".

True, the government acknowledges that the declaration should have protected the political rights of the Arabs of Palestine. But it fails to acknowledge Israel's stubborn denial of the Palestinian right to national self-determination and Britain's own complicity in this ongoing denial. Britain's rulers, like the Bourbon kings of France, have apparently learnt nothing and forgotten nothing in the intervening 100 years.

- Avi Shlaim is an Emeritus Professor of International Relations at Oxford University and the author of The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World (2014) and Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations (2009).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: UK foreign secretary Arthur James Balfour and his 1917 letter (Wikicommons)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.