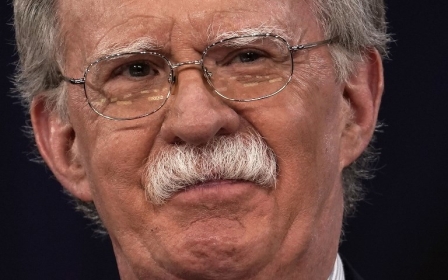

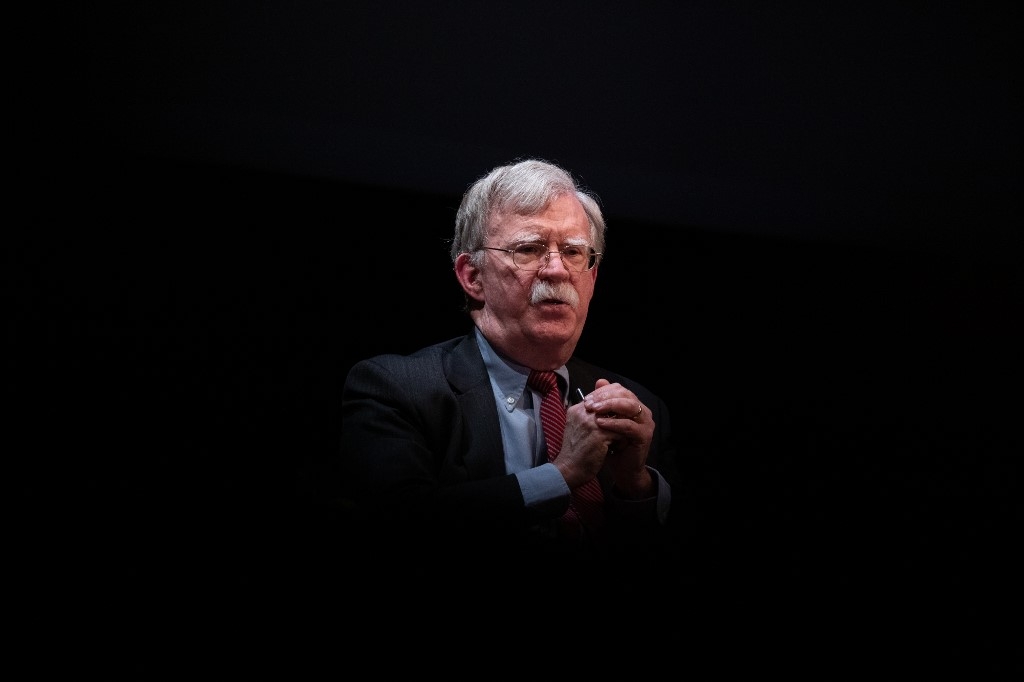

John Bolton's memoir makes him look far more dangerous than Trump

Much has been written in recent days about former US National Security Adviser John Bolton’s revelations about President Donald Trump’s many inadequacies.

Media reviews of his memoir, The Room Where It Happened, have highlighted Bolton’s excruciating examples of the president’s lack of concentration, ignorance, inconsistency, corruption and narcissism. Others have highlighted Bolton’s failure to volunteer evidence against Trump during impeachment investigations.

What most reviewers have ignored, however, is the light that Bolton’s book throws on Bolton himself. It shows him to be a far more dangerous figure than Trump himself, and not just because he, Bolton, is smarter.

Unremitting arrogance

The former adviser comes across as unremittingly arrogant, unreflective and simplistic - a man who holds views on the world that are more short-sighted, one-dimensional and radical than Trump’s. What a relief that he is no longer in power.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Long before Trump took it up as a political slogan, the bedrock of Bolton’s thinking was America First, complete with contempt for international cooperation in solving world problems.

Early on in the book, where he proudly boasts of his several invitations to the White House to explain things to Trump even before he was given a job, Bolton shows his mettle. “I congratulated Trump on withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement… which I saw as an important victory against global governance,” he writes. He throws aside the Iran nuclear deal as “abominably negotiated”.

'I congratulated Trump on withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement'

- John Bolton

He says he warned Trump “against wasting political capital in an elusive search to save the Arab-Israeli dispute”, and gives himself credit for advocating the US decision, which Trump later took, to cut funds to the UN agency that helps Palestinian refugees. In a further slap to global governance, he says he wanted the US to pull out of the UN Human Rights Council.

Instead of international negotiations, Bolton’s favoured methods of dealing with countries with which the US has disagreements are unilateral sanctions and pre-emptive military force.

One of the recurring refrains in Bolton’s memoir is his bureaucratic tussling with US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin over the extent and sweep of US-imposed financial sanctions. Whether targeting Russia, Iran or Venezuela, Bolton portrays Mnuchin as excessively cautious and worried about the international system. He describes the state department as equally obstructive and therefore weak.

'Massive conventional bombs'

Resort to military force is Bolton’s hobbyhorse, and here, his bureaucratic opponent - regularly pilloried in the book as a ditherer - is former defence secretary James Mattis. In one of his early conversations with Trump, Bolton reveals that he explained “why and how a preemptive strike against North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic-missile programs would work”.

A powerful argument against such a move by the US has long been the risk that North Korea would retaliate by firing multiple salvoes of conventional missiles at the South Korean capital, Seoul. Analysts believe that more than a million people could be killed.

Bolton’s solution? At the same time as striking North Korea’s nuclear facilities, “we could use massive conventional bombs against Pyongyang’s artillery north of the [Demilitarised Zone], which threatened Seoul”. Bolton calls North Korea “a rat-shit little country."

Needless to say, Bolton also tried to convince Trump to start a war with Iran - and not just over US suspicions about Iran’s nuclear potential. In a chapter titled “Trump Loses his Way, and then his Nerve,” Bolton discusses the White House talks over how to respond to suspected Iranian attacks on oil tankers in the Gulf in June 2019. The Joint Chiefs of Staff proposed a “tit-for-tat” and “proportionate response”.

Bolton reveals that he favoured a disproportionate one, so as to “convince Iran it would face costs far higher than it was imposing on us or our friends”. He suggested bombing Iranian oil refineries. He was deeply upset when Trump gave an interview to Time magazine the next day and downplayed the Iranian attacks as “very minor”. Bolton thought of resigning. “I wondered why I bothered coming to the West Wing every morning,” he writes.

Threats of all-out war

But worse was soon to come, from Bolton’s point of view. The Iranians shot down an unmanned US drone over the Strait of Hormuz. The Pentagon upped its proposed response and suggested hitting a handful of Iranian missile launching sites.

To Bolton’s satisfaction, Trump agreed to strikes this time - but then, a few hours later, just as the US was about to go into action, changed his mind for fear of causing too many casualties. Bolton was furious: "In my government experience this was the most irrational thing I ever witnessed any President do," he thunders.

Bolton had better luck with regards to Syria. On the very weekend he took on the job of national security adviser, the White House was planning how to react to a chemical incident with dozens of casualties in the Damascus suburb of Douma in April 2018.

Bolton produces some interesting detail. He reveals that before Trump was ready, French President Emmanuel Macron and British Prime Minister Theresa May were eager for an early military attack on Syrian government facilities, on the assumption that President Bashar al-Assad’s forces were responsible.

The Syrian government denied responsibility and agreed to let inspectors from the international watchdog, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), visit Douma and investigate. In several pages on the affair, Bolton says nothing about this, leaving the impression that none of Washington, London or Paris discussed holding the strikes back until the OPCW investigators had arrived in Damascus to start work and reach conclusions.

The three countries launched air strikes on a scientific research centre in Damascus and several Syrian military storage sites. To his credit, Bolton records that UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called the strikes inconsistent with international law, because they were not authorised by the Security Council. But Bolton makes it clear he thought the air strikes were weak. In effect, he believed the US should have launched all-out war.

As he puts it: “We should have destroyed other Syrian military assets, including headquarters, planes, and helicopters… and also threatened the regime itself, such as by attacking Assad’s palaces.”

Silence on Libya and Yemen

This was the third major crisis where Bolton was more hardline and trigger-happy than Trump. Bolton is both angry at this and, with his trademark arrogance, proud. He happily quotes Trump’s reply to a reporter who asked whether he was satisfied with Bolton’s advice: “John… has strong views on things, but that’s okay. I actually temper John, which is pretty amazing, isn’t it?”

Bolton’s memoir is surprisingly unforthcoming about other hot Middle Eastern issues, such as Libya and Yemen. Oddly, he calls the latter “a British obsession”. Did this comparative silence on two countries racked by civil war and outside intervention mean the White House was not engaged in policy options there?

Trump is wild and unpredictable, and we cannot relax as long as he is US president - but with Bolton now gone, things are considerably less bad

There are only a few paragraphs on the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, suggesting there was no serious discussion, let alone dissent, within the Trump administration about its unwavering alliance with Saudi Arabia and the continuation of massive arms sales.

Bolton lacks nuance and is even ill-informed, about the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) militia. He brands them simplistically as terrorists, asking why the US should help them against the Islamic State (IS) group. Apparently, he sees no distinction between a group that is defending its homeland and the genuinely terrorists of IS. In his words: “Why we were affiliated with one terrorist group in order to destroy another stemmed from Obama’s failure.”

He similarly lumps the Taliban in with al-Qaeda and IS as terrorists, not seeing the difference between two groups with an expansionist ideology and the Taliban, who want to seize or share power in their own country and have no global ambitions.

Narcissistic faith

Bolton is right to criticise Trump’s sudden whim last year to invite the Taliban to Camp David even before an agreement on a ceasefire, let alone a wider political settlement, in Afghanistan. The move was aborted. Trump’s meetings with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un had already shown that theatrical face-to-face encounters between leaders rarely produce solutions, unless earlier diplomatic negotiations have developed serious prospects for compromise.

But we should not blindly ridicule Trump’s narcissistic faith in his ability to charm adversaries. It’s better to err by putting too much faith in meeting for meeting’s sake, when the alternative on offer is a Bolton-esque faith in military strikes.

Of course, Trump is wild and unpredictable, and we cannot relax as long as he is US president - but with Bolton now gone, things are considerably less bad.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.