Brazil election: A Lula victory could pull country back from the abyss

In the first round of Brazil’s election this month, former president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, won 48 percent of the vote while far-right President Jair Bolsonaro trailed with 43 percent.

Lula won more than 57 million votes, exceeding Bolsonaro’s total by more than six million. Yet while it was a clear victory, the left has not been in a celebratory mood. The near-existential stakes have never been more apparent, as the country faces a tense wait for the second round of voting on 30 October.

Bolsonaro, who was threatening a coup even before he took office, performed significantly better than polls had suggested. Despite presiding over a government that has turned Brazil into a semi-pariah state, Bolsonaro won 51 million votes, around two million more than he received during the first round in 2018. It is difficult to understand how a president responsible for what is widely regarded as among the world’s worst public health responses to Covid-19, along with environmental disaster and widespread hunger, managed such a feat.

Another Bolsonaro victory would almost certainly spell the end of Brazil as a democracy, and in several important respects, as a functional society

After nearly a decade of economic and political crisis, Brazil’s New Republic, established in 1985 after 21 years of military dictatorship, is hanging by a thread. The second round, even more so than the first, is what analyst Alex Hochuli terms a plebiscite on democracy itself: a vote for Lula is a vote for the New Republic, and a vote for Bolsonaro is one against it.

Another Bolsonaro victory would almost certainly spell the end of Brazil as a democracy, and in several important respects, as a functional society. He would likely pack the Supreme Court with allied judges and remove his government from any sort of public oversight. This is a country where authoritarian politics are the norm rather than the exception, and Bolsonaro and his allies have been explicit about their goals.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In the run-up to the election, the president questioned the integrity of Brazil’s electoral system and threatened a Trump-like insurrection in the event of a Lula victory. As Bolsonaro’s running mate, retired general Walter Braga Netto, put it: “Either we have clean elections, or we won’t have elections.”

As for turning Brazil into a non-viable society, a Bolsonaro victory would hand over the country’s already gutted public sector to a powerful alliance of private interests, abandoning the majority of Brazilians in the process.

Far-right domination

With that out of the way, let’s dig deeper into the results themselves. First, the good news: the Workers’ Party regained some ground, increasing its number of federal deputies in Congress to 68 from 56, while its leftist allies boosted that number further to 79. Now for the bad news: both chambers of Congress are now more than ever dominated by the extreme right, as Bolsonaro-aligned politicians won the most seats in each. The president’s Liberal Party is now the single largest party in Congress, with 99 seats.

Those elected included many of the figures responsible for overseeing the most disastrous aspects of Bolsonaro’s first term, such as disgraced former justice minister Sergio Moro, elected as a senator for Parana; former health minister General Eduardo Pazuello, elected as a federal deputy for Rio de Janeiro after leading Brazil’s criminally incompetent Covid-19 response; Vice President Hamilton Mourao, elected as a senator for Rio Grande do Sul; and former human rights minister, Damares Alves, who has denied allegations that she was involved in a scheme that trafficked indigenous children.

Demographically speaking, Brazil has proven to be somewhat of an exception to the familiar narrative of class dealignment, in which social democratic parties lose working-class votes to an insurgent far-right. The Workers’ Party was able to recover many of the votes it lost in 2018, while Bolsonaro maintained support among the middle class.

Still, after four years of almost unmitigated disaster, those responsible proved electorally popular. Brazil’s extreme right is now firmly entrenched as a powerful electoral bloc with control of key institutions, largely at the expense of the centre right, which now exists primarily in the pages of Brazil’s major newspapers.

How did this come to pass? Let’s start with the most obviously materialist explanation: Bolsonaro allies directly benefitted from what Bruno Brandao, executive director of Transparency International Brazil, described as “the biggest scheme to institutionalise corruption in the history of Brazil”.

This scheme, known as the secret budget, effectively allowed funds to be channelled towards deputies allied with Bolsonaro, without any discretion or real oversight. This mechanism has been used to effectively buy off members of Congress and prevent dozens of impeachment requests against Bolsonaro from making any headway.

The scale of the secret budget is vast: whereas the vote-buying scheme that nearly brought down Lula’s first government in 2005 involved a figure of around 100 million Brazilian reals ($19m), the secret budget so far has accounted for 44 billion reals ($8bn).

Consolidating powers

To give an indication of what this looks like in practice, the town of Pedreira reportedly justified the funds it received via the secret budget by claiming they were used to perform more than 540,000 tooth extractions, or 14 teeth for each resident, including toothless newborns.

This vast amount of money has been used to consolidate the powers of Bolsonaro's allies, in effect institutionalising the far right’s hold on Brazil’s Congress. The “old politics” of influence-trading that Bolsonaro promised to eliminate have been replaced by the “new politics” of corruption on steroids, with an unhealthy dash of demented conspiracy theories, guns, bigotry and other staples of Bolsonarista politics.

Congress has also allowed Bolsonaro to turn on the taps of public spending in the form of conditional cash transfers. In July, Congress passed an amendment allowing Bolsonaro’s government to spend an extra $7.6bn on social programmes until 31 December. It would appear that Congress found a “magic money tree” to buy votes for itself and the president in the run-up to the election.

At the same time, the Bolsonaro government has continued to dismantle and defund public services, recently blocking more than 2.4 billion reals ($453m) in financial resources that would have gone to the education ministry.

Of course, this isn’t the only reason for the continued rise of the far right. There is also the fact that anti-Workers’ Party sentiment remains widespread, and many ultimately decided to hold their noses and vote for Bolsonaro as “the lesser evil”. And as depressing as it is, Bolsonaro still has a significant social base that he can mobilise.

Prosperity gospel

The reasons for this are not only ideological, but also material: most obviously, the continued deindustrialisation of Brazil and the shift towards the export-driven agricultural economy has resulted in significant social and political changes.

On another level, it would be easier for illegal loggers and gold miners to make money in the Amazon if what remains of Brazil’s environmental restrictions are removed. As philosopher Rodrigo Nunes told me, for many among Brazil’s new precarious working class, such as food-delivery drivers, the institutions of a viable society - health and safety regulations, traffic laws and labour codes - get in the way of the little money they make.

Viewing themselves as entrepreneurs who rise according to a meritocracy, these same precarious workers subscribe to the individualised prosperity gospel of evangelical churches, rather than the social gospel that was once promoted by the Catholic Church. This is a complicated issue that the left, trade unions and analysts must take notice of going forward.

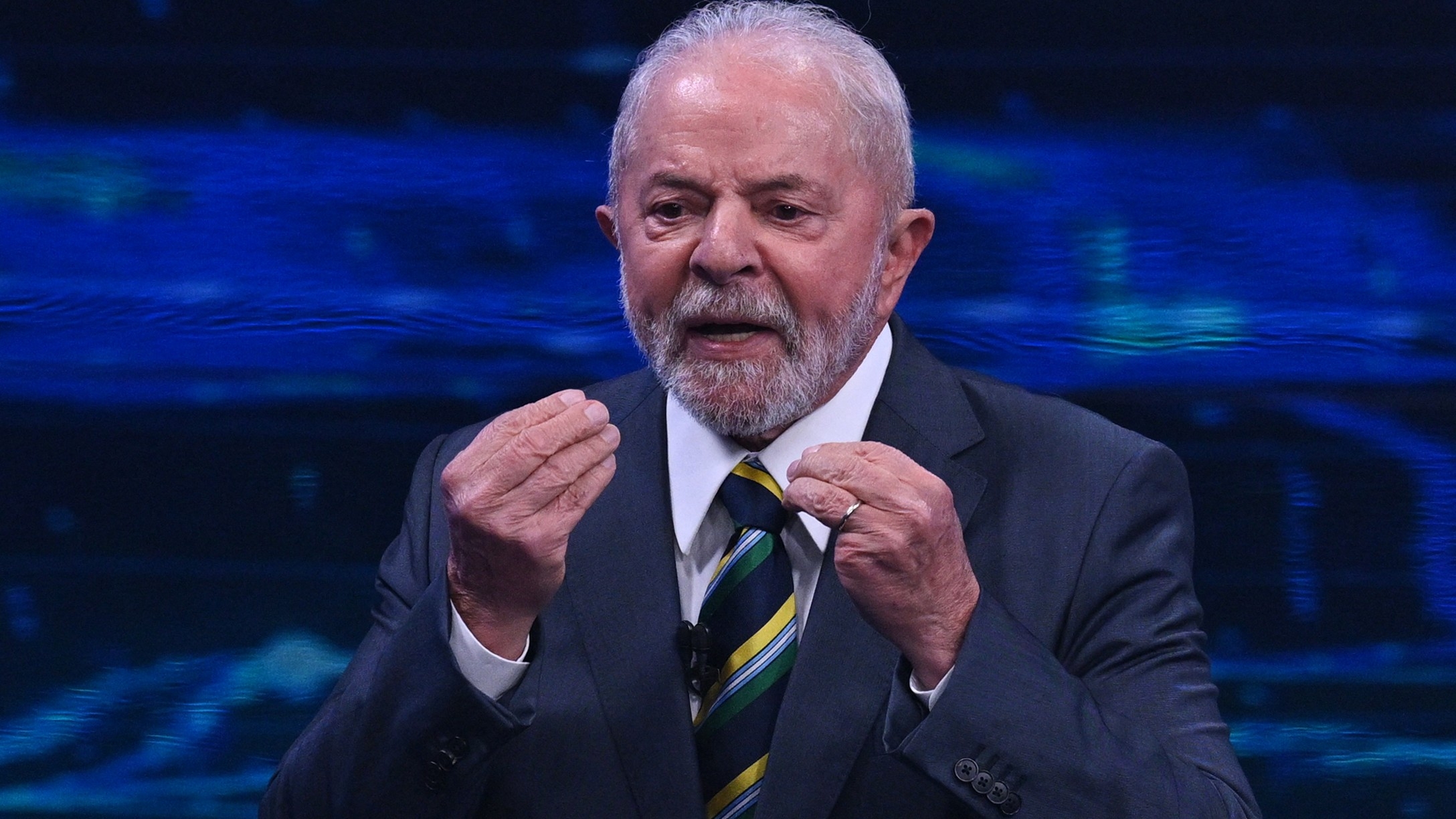

If Lula does indeed win, it would mark the culmination of one of the greatest political comebacks of all time

Despite all of these institutional obstacles, Lula remains the favourite; in order to emerge victorious on 30 October, he has to win enough support from third-party voters and those who decided to abstain to get him across the finish line. This would require far less than the additional numbers that Bolsonaro would require to win.

Already, the two most important third-party candidates have endorsed Lula: the centre-right Brazilian Democratic Movement’s Simone Tebet, who finished in third place, gave a stirring endorsement in which she emphasised Lula’s commitment to democracy, while the Democratic Labour Party’s Ciro Gomes offered a far less enthusiastic endorsement, releasing a video in which he refused to even utter Lula’s name.

If Lula does indeed win, it would mark the culmination of one of the greatest political comebacks of all time. A few years ago, Lula was in prison on trumped-up charges, and the Brazilian opposition was rudderless and fragmented; now, he is the favourite to win the presidency, leading a broad coalition.

A victory for Lula would not only be a victory for Brazilian democracy; it would also show the world that there is a way out of the abyss, providing a source of inspiration for those around the globe who dream of a better future.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.