Brexit: Is right-wing populism the new norm?

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity. It was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.”

The famous opening of Charles Dickens' Tale of Two Cities serves as an apt description of Britain's decisive lurch into indecision.

The EU referendum was borne out of a furious new strain of nationalism riding on the collective and individual failures of the European community to address the refugee and migrant crisis. Even the 2008 economic crisis did not cause such an outpouring of sentiments. The shocking divorce comes four years after the EU was awarded world’s highest honour, the Nobel Peace Prize, for “the successful struggle for peace and reconciliation and for democracy and human rights.”

What is left now is to manage a smooth departure and write a script for the post-departure EU-Britain relations. But the real challenge for the Leave campaigners is to prove how their future will be different from the past, other than making Britain unfriendly for immigrants.

The most important question that will shape the future of Britain, not Europe, is how to respond to the increasing and deepening crisis of migration. The UK has always been reluctant to accept any collective measure, particularly any EU decision on the current refugee crisis. With this backdrop came the EU-Turkey refugee deal which distributed the incoming refugees through a quota system or levied a financial penalty in exchange for a country not accepting its quota.

Like most other big and resourceful countries - Germany excepted - Britain has shown little interest in accepting Syrian refugees. Since 2011, the UK has accepted some 5,000 refugees from Syria, a tiny fraction of the numbers accepted by Syria's neighbours Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. As the UK is not part of the EU-Turkey refugee deal, all David Cameron could promise was to accept only 20,000 refugees from Syria by 2020 under the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Programme (VPR), .

Even with such a modest intake of Syrian refugees, the Leave campaigners have not hesitated in using depressing images of refugees arriving in Europe en masse to create an extreme sense of being overwhelmed by refugees should Britain remain with Europe.

Their scream, “the Turks are coming” publicised through daily tabloids, not only questioned the visa liberalisation and EU accession for Turks, it also questioned the entire EU-Turkey deal. That the deal has brought down significantly the number of illegal immigrants was not given any merit, even by the pro-EU camp.

In its natural trajectory, the anti-immigrant rhetoric developed and deepened the Turk-phobia by wrongly propagating fears that nearly a million Turks will settle in Britain if Turkey accedes to the EU by 2024.

Instead of defending Turkey’s right to join the EU, Cameron was forced to say that Turkey has no prospect of joining EU in the next 1,000 years. His defence of the Remain campaign suggests that the anti-immigrant and anti-refugee rhetoric is becoming a new norm worldwide. Visa-free travel to Schenegen countries for Turkish nationals also became a reason to drum up fear and anxiety, even though Britain is not part of the visa-free Schengen area.

Nonetheless, if Turkey becomes a full member of the European Union, mass migration from Turkey to Britain is a far-fetched projection. With Leave having won, the EU-Turkey refugee deal needs to be given more credibility and legitimacy from its member states.

Turkey has indeed lost one of the most important supporters for its European Union ambitions and as a result, it is an open question as to who will assure the fair and timely implementation of the deal.

Nevertheless it also offers an opportunity to rescue the European Union from its gradual collapse, as Turkey’s core interests lie with the unity of the EU. A disintegrated Europe does not offer any promising future for Turkey’s economic and security priorities. Turkey has been accusing the EU of backtracking from the visa liberalisation for Turkish citizens as promised in the refugee deal, but the delay is perhaps better than the disintegration of the union.

There are reasons to believe that the Brexit campaign was fundamentally misinformed and emotive. How come that the most developed democracy has no space to educate its nationals about the real causes of the crisis? It is surprising that British voters are not sensitive to the humanitarian disasters happening in a part of the world where their country has major stakes.

It is the indecisiveness of the world powers, including the UK, which is responsible for the prolonged bloodshed in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere. The most important lesson, which was never accepted by the Leave campaign, is that isolating the UK from EU will do very little to stop UK-bound illegal immigration. In an extremely insecure environment, refugees will continue migrating for their security and livelihood towards more secure places.

It is not surprising that the forces which are responsible for the prolonged civil war, by supporting the Assad regime’s bombing of civilians, mainly Russia and Iran, are seen as welcoming the outcome. Since most of the fleeing Syrians are from opposition areas, where Assad regime and Russian air strikes continue, they see the current anti-refugee sentiments in Europe as an opportunity to justify their opposition-focused anti-terror discourse. It is how major ideologies such as the Islamic Revolution of Iran, socialism and Islamophobia join hands to create fear of refugees becoming a source of extremism and terrorism.

As of now the most important question is how to secure meaningful cooperation around the issue of Syrian refugees from both Europe and the UK. The Brexit campaign has already questioned everything, however limited and insufficient, that the EU and the UK were doing for the Syrian refugees.

With Brexit implemented, the UK will lose its right to return the refugees under the Dublin regulation, which allows EU members to return refugees to the country of their first entry into Europe. The Dublin regulation had already completely failed when nearly a million refugees had flocked to European borders via Greece in 2015.

Though Brexit will not affect the UK’s international obligations toward refugees and immigrants, as required under the 1951 Refugee Convention and related protocols, its closing the door to further refugees will effectively put in question the international system. Post Brexit, even with the reinforced demarcation between the two sovereign entities that Leave promises, EU-UK relations are unlikely to radically change since both need each other.

But the UK’s sudden plunge into anti-refugee and anti-immigrant politics could create an entirely new, right-wing political populism on the world stage, risking the rights of minorities, refugees and victims of conflicts caused by international powers.

- Omair Anas is Delhi-based commentator and analyst. You can follow him on Twitter @omairanas

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

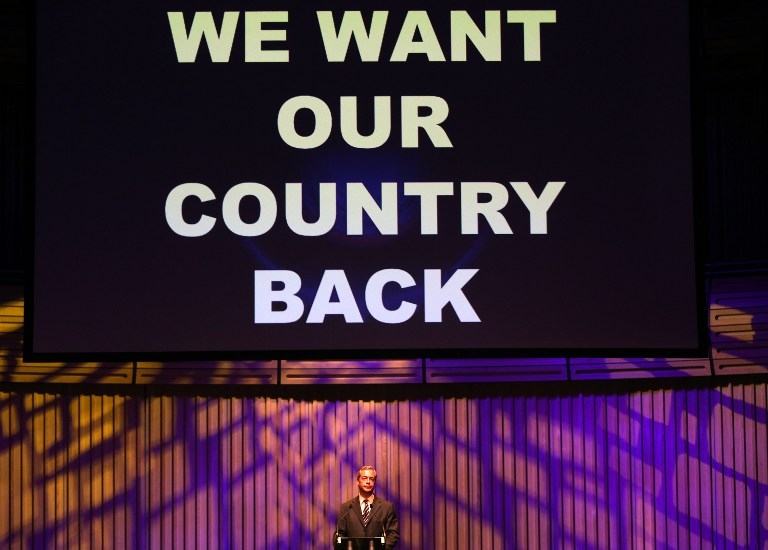

Photo: Leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), Nigel Farage, speaks at a public meeting of the EU Referendum campaign in Gateshead, north east England on 20 June, 2016 (AFP).

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.