Suez to Prevent: Britain's propaganda is still misreading the Middle East

In 2005 after the London bombings, Boris Johnson wrote in the Spectator magazine that it was only natural for the public to be scared of Islam.

"Judged purely on its scripture - to say nothing of what is preached in the mosques - it is the most viciously sectarian of all religions in its heartlessness towards unbelievers.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

After the Manchester bombing in 2017, then prime minister Theresa May urged world leaders at the G7 summit in Sicily to do more to combat online extremism. The fight against the Islamic State group was “moving from the battlefield to the internet”.

As Mark Curtis wrote in his excellent book Secret Affairs: Britain’s Collusion with Radical Islam, Britain has a long history of supporting and training radical Islamic groups from Afghanistan and Pakistan to Kosovo and Libya.

But to deal specifically with the production of radical Islamic texts, which Prevent and successive prime ministers appear to think is such a danger to our universities, it comes as little surprise to learn that one of the major production houses of incitement in the Muslim world was indeed the British government itself.

The innocently named Information Research Department (IRD) nestling in the Foreign Office was churning out sermons. Recently declassified official papers show that the IRD commissioned a series of sermons that were reproduced and distributed throughout the Arabic-speaking world.

The secret unit arranged for articles to be inserted in magazines published by Al-Azhar University in Cairo “to ensure that every student leaves the University a resolute opponent of communism”.

Why Al-Azhar University? Because the declassified papers say “from among them come the imams who preach the Friday sermon in every Egyptian mosque; the teachers of Arabic in the secondary schools and all teachers in the village schools; and the lawyers specialising in Moslem law”.

Fake news

Apart from the ever pliant Reuters and the BBC, the IRD had its own news service - the Arab News Agency (ANA), one of several media organisations that British intelligence had set up during the Second World War.

But not content with that, it even ventured into literature, publishing romantic and detective novels, within which anti-communist messages were subliminally embedded.

I stumbled across this ultra-secret MI6 propaganda unit by accident. I was interviewing a delightfully indiscreet Palestinian in Amman about his dealing with Israel, particularly over Jerusalem.

Abu Odeh described the process of inserting fake news into real news and making it believable

Adnan Abu Odeh in his day as King Hussein’s information minister had courted no small amount of controversy. Today he is treated with great respect.

As a young intelligence officer, Abu Odeh rose through the ranks of Jordan’s mukhabarat until he caught the attention of King Hussein, with whom he developed a personal relationship.

“He always looked at me as that young man in the mukhbarat who had a good mind. Always he talked to me like this. He used to bring me as minister of information to issues to be discussed only by him and the prime minister. It never happened that the king would invite the minister of information to come and talk, except me. It is because I was daring enough to tell him the truth. “

He became minister of information before the infamous Black September clashes in 1970 when Jordanian planes - and Israeli ones - bombed Yasser Arafat’s PLO camps in Jordan, forcing the fedayeen out of the cities, until they were surrounded in a forest and surrendered.

They were escorted out of the country by the Syrians to Lebanon. When I met him in 2018, Abu Odeh still referred to these events as “ White September”.

Before appointing him as a minister in his government, Hussein wanted his young intelligence officer with a good mind to be trained in misinformation by the professionals.

That’s it how Abu Odeh found himself on a week-long course at the IRD. At first he bridled.

'That was May 1970 just four months before (Black September). The king was preparing me to become minister of information, but upon the advice of MI6'

- Adan Abu Odeh

“What have I to do with it? I am an intelligence officer. I did not know but later on, after a year, my director of intelligence invited me to his office and said to me: “His Majesty wants you to go to a course at Salisbury War College on psychological warfare. I went. That was May 1970 just four months before (Black September). The king was preparing me to become minister of information, but upon the advice of MI6.”

I asked him what he learned.

Abu Odeh described the process of inserting fake news into real news and making it believable.

“The IRD department is divided into desks for Russia, Bulgaria, Romania, Lithuania and each desk knew the language of their country. So this information in each’s countries national and local media, culled from their embassies, arrives at this desk. And this desk officer reads them.

“He has a mind. He has to think. I mean he is not an ordinary man. He has to use this information to rewrite it, or reproduce it and send it abroad, either through the BBC or through journalists, without making readers think it has been reproduced. It’s a very smart way. So that was my course, to become smarter.”

From Suez to Iraq

Much of this effort was directed at the Soviet Union. This was the prism through which they saw the Middle East and it distorted their reading of it, as neoconservative anti-Islamic campaigns do now.

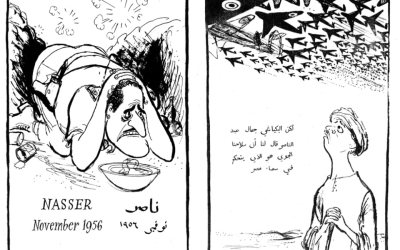

In March 1956, the UK Foreign Office instructed the IRD to switch its focus away from communism and towards Egypt led by Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Nasser had been engaged in propaganda operations against the British for some years, particularly though the Sawt al Arab or Voice of the Arabs radio station in which he taught the Arab world the potential of nationalism to break the monopoly of imperialist power. Nasser first coined the phrase “the Arab street”.

The IRD thought of Nasser as a potential communist rather than an Arab nationalist, who outplayed them at their own PR game. An IRD paper written in Cairo in 1950 noted: “Conditions in Egypt are such as to make it eminently suitable breeding ground for communism.”

Prime Minister Anthony Eden, the one-time poster boy of the Tory party, the youngest foreign secretary in British political history who could speak Arabic to boot, was undone by the Suez crisis from which he, and Britain, never recovered.

As Vyvyan Kinross writes in Information Warriors: The Battle for Hearts and Minds in the Middle East to be published next week: “It is hard to completely escape the parallel in this aspect of Eden’s premiership with that of Tony Blair’s flawed rationale and media manipulation prior to the invasion of Iraq 40 years later, finally laid bare in the Chilcot Report. In his role as architect of Britain’s information wars over Suez, Eden can truly be said to have designed a house with no stairs.”

The IRD has long been disbanded, but its methods and their conceit that you can fashion public opinion in faraway lands like soft wax continues on.

Same old song

The plaforms have changed but the tactics and regional actors remain the same. The US State Department’s Global Engagement Center (GEC), was set up in 2016 in order to “counter propaganda and disinformation from international terrorist organisations and foreign countries”.

Richard Stengel, then undersecretary for public diplomacy and public affairs at the State Department, told a foreign affairs committee hearing about “Countering the Virtual Caliphate” in July 2016 that the GEC was working with Cairo’s Al-Azhar University “to try to help get the message that ISIL is anti-Islamic, that it is a perversion of Islam out in a way on platforms that they traditionally don’t use”.

Elaborating on the GEC’s work with religious scholars in the region, Stengel said: “We can help give them greater capability, help streamline their message. I have talked to the people at different Islamic universities in saying ‘here is how you shorten a 68-page fatwa to three different tweets’. That is more effective.”

To change the Middle East, you have to understand it, and this Britain has consistently failed to do from Suez to the present day.

The anti-Islamic strain of British government today, both at home and abroad; the UK’s willingness to court and train despots who bred religious extremism even more vigorously than they suppress it; the UK’s absolute insouciance toward the Arab street - all of this marches cheerfully to the same tune.

Britain has learned nothing from its disasters in the Middle East. Its right for a fresh wave of refugees from Syria to be heading for Britain and Europe, because they, in all of their doomed intrigues, share the responsibility for creating them.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.