Chemical weapons, Seymour Hersh, and propaganda in Syria

Seymour Hersh has made a career out of scaring powerful people in high places. His uncover of the My Lai massacre in 1969 in which it was revealed that American troops in Vietnam had massacred hundreds of unarmed villagers – and that the army had covered it up – made his name as one of America’s most fearless investigative journalists.

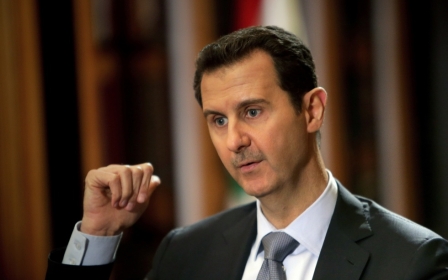

Which is why a series of articles released in the London Review of Books claiming that the notorious Sarin gas attack in the Ghouta region of Damascus in Syria last August may not have actually been the fault of the Syrian government, have not been simplu dismissed as the feverish dreams of a conspiracy theorist. Hundreds if not thousands of people are thought to have been killed in the attack – the estimates vary wildly depending on the source – and accusations began to fly almost immediately as to who was the culprit. The opposition and their supporters were quick the level the blame at Assad, who is known to have had a sizeable stockpile of chemical weapons, produced primarily as a counterbalance to Israel’s nuclear programme. The Assad government immediately laid the blame on rebel forces, with Russia quick to back up that assertion.

Hersh’s latest article suggests that, effectively, the attack on Ghouta was a false flag operation conducted covertly by the government of Turkey, with the intention of provoking the Americans and NATO into launching a military intervention in the country.

Were the revelations true, it would obviously be political dynamite. Erdogan’s government has already been in hot water over a leaked video on YouTube in which the head of the security services, Hakan Fidan, talks of the potential of launching a false flag attack on Turkish soil.

“I'll send 4 men from Syria, if that's what it takes. I'll make up a cause of war by ordering a missile attack on Turkey; we can also prepare an attack on Suleyman Shah Tomb if necessary.”

Erdogan's reaction – closing down YouTube saying he wouldn't let it “devour” people – would seem to confirm that he is sensitive to these accusations.

A poll conducted by Kadir Has University showed overwhelmingly that the Turkish public is opposed to unilateral intervention in Syria, with 79 percent saying that only the “existence of a direct threat against Turkey” would justify military action. In light of this, it would be difficult for Erdogan – who is known to be a hawk when it comes to Syria – to convince the Turkish people of the validity of going to war with its neighbour without a major game-changing event. An attack on the Suleyman Shah tomb, which contains the remains of the grandfather of the founder of the Ottoman Empire, Osman I, would clearly be such an event. As would the potential threat of a chemical weapons attack. And since Erdogan would have to be mad to start a war without support from its more powerful NATO allies, there would need to be need be an almost existential threat.

All of this fits neatly into a conspiracy theory, but Turkey has denied the claims and US state department spokesperson Jen Psaki has reaffirmed the Americans’ original conclusions:

“In light of our reports and intelligence we had received, we believe beyond any doubt that the attack on 21 August had been carried out by the Syrian regime and we are still behind the same view shared by the international community.”

Paul Schulte, Senior Visiting Fellow in the Centre for Defence Studies at King's College London, agrees that the scenario seems implausible and questions Turkey’s ability to even carry out such an operation.

“The capability of sending sarin in and arranging for it to be fired in by Al-Nusra in ambiguous circumstances…who knows? What you’re describing is a kind of intelligence black op, it’s hard to do, no organisation specialise in this, and chemical attacks are rare. Could one say that any country had the ability to do it with the kind of confidence and deniability and utterly successful suppression evidence that you’d need if you were going to pull that off? I remember when first consulted about this, and it was being suggested that the rebels had done it themselves – well, you’d have to be very, very confident that you could survive the investigation long term to take that kind of a risk that would destroy your believability and international sympathy. I don’t think the rebels were that confident, I don’t think the Turks could have been that confident!”

The difficulty with Hersh’s journalism, according to Schulte, is that it requires his readers to make a leap of faith:

“It relies very much on his personal credibility, which means the veracity and credibility of his sources, both to the extent that they are telling him what they think to be the truth and also what their knowledge access is to that truth. And although Hersh is a big name going back to Vietnam, I am not persuaded and I haven't picked up any vibrations on my network that here he is saying anything that is going to be widely believed or credible and that's a problem because he is not relying on any evidence that can be traced, he is relying on a series of unnamed contacts.”

The arrest of 12 terror suspects in Turkey with alleged links to the Al-Nusra Front again stoked the blogosphere when it was initially suggested that they had in their possession 2kg of sarin nerve gas. Later, however, Turkish officials later changed their assessment claiming that they were instead in possession of “anti-freeze”.

Jeremy Salt, an associate professor of Middle Eastern history and politics at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey, says that Hersh’s article holds a lot of merit:

“There are people here [Turkey] that don’t like this government, but they’re still saying this is still so outrageous it can’t possibly be true, it’s a conspiracy theory – they can’t prove that it’s a conspiracy theory, but they’re saying it.”

He dismisses claims that Hersh could have been duped by false documents, as alleged by Jeffrey Lewis in the security blog Arms Control Wonk:

“Seymour Hersh is a very experienced reporter and he’s been dealing with these people for decades – he’s not the kind of person who’s going to be sucked in by someone giving him a false document and trying to pull the wool over his eyes. My view is that this was a false flag operation pushed by someone. I thought, first of all, because there was some evidence for this, it was pushed by Saudi Arabia. But we don’t really know the truth. Now Seymour Hersh has come up with this new line that Turkey somehow was involved and here, people find this very hard to believe and the Turkish government has denied it outright. But on the other side the people who try to discredit Hersh, many are people who want to blacken the name of the Assad government.”

Numerous points of controversy have marked the debate over the chemical attack. The issue over the viability of rockets being launched from rebel positions or army base positions has been one such contention. A battle of evidence has emerged between Hersh and the Brown Moses blog run by weapons analyst Eliot Higgins. After the publication of Hersh latest article – which claims there is evidence the rockets used Ghouta were of amateur design, improvised and therefore more likely originating with the rebels – he released another countering his claims.

"Seymour Hersh fails to address how eight to twelve 2 meter long perfect copies of Volcano rockets were produced and transported from Turkey to Damascus, along with hundreds of litres of Sarin precursors, and the required equipment to mix it and pour it into the warheads."

On Sunday 13 April, Associated Press reported another chemical gas attack had allegedly taken place in a rural village north of Damascus. The report is primarily based on amateur video, which has been par the course for so much of the reporting coming out of Syria. As usual both sides have blamed each other.

One of the main reasons why the debate continues is that the report released by the UN into the original attacks in Ghouta did not apportion blame and the issue of culpability has, seemingly, fallen off the geopolitical agenda. Since the process to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons began, both the US and Russia – as the main advocates – have said little with regards to who was to blame for the chemical attack.

The success in convincing Assad to agree to give up his stockpile, half of which has now been removed from the country, has been hailed as a diplomatic victory by both sides. It made Putin look like a kingmaker – the man who through diplomacy and level-headedness managed to prevent a Western invasion of Syria. And it provided Obama with a neat way of retreating from a military intervention without looking weak and ineffectual. As such, to muddy the waters further with new revelations – while the death toll in the war creeps ever higher with only the use of conventional weapons – would hardly benefit any of the international players.

An exchange on the BBC Radio 4 programme ‘File on Four’ on Tuesday 7 January 2014, featuring an interview with Hugh Greeg of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons cast some light on the situation:

Reporter: “Syria’s declared all its precursor chemicals, so OPCW has access to those chemicals now, don’t they?”

Hugh Gregg: “Our inspectors have access to them. Whether there’s a legal agreement or not for taking a sample and shipping it to a designated lab or to our laboratory is now a political question, not a technical one.”

Reporter: “Technically, you could narrow this down if you had the mandate to do so?”

Gregg: “We have the technical capability to do that, that’s correct.”

Later in the same programme, the report put the question of culpability to Malik Ellahi, another spokesperson for the OPCW:

Ellahi: Well, as you know there was an investigation and it actually proved that chemical weapons were used in Syria. There was no attribution as such, but I mean chemical weapons anywhere in the world is a serious problem for anyone.

Reporter: Have Syrian rebels used chemical weapons?

Ellahi: We have absolutely no idea of verifying that.

Reporter: That is troubling, isn’t it? The fact that you can’t verify who has done this?

Ellahi: It is troubling, but at the same time I think the solution was to get rid of chemical weapons from Syria and that’s what the international community agreed on eventually.

I contacted the OPCW to elaborate, but was told they would not be commenting on the issue of culpability.

“I find the media position on this is 'well, it's all going well, it's a triumph for international cooperation' and all the attention's turning to the Ukraine so nobody's interested,” says Schulte. “But in fact it seems to me very interesting that the international community is incapable of systematically investigating the murders of 1500 people, in front of TV cameras! But until there’s a detailed investigation of evidence rather than this sort of throwing around of hearsay, we’re not going to know. That’s why I think public attention should be focusing on where the blinkers are coming down to prevent available evidence being cross compared. Who is doing this? Under what pretext?”

The Gulf of Tonkin incident, which brought America into the Vietnam after North Vietnamese ships allegedly fired on an American navy vessel, was for decades the stuff of conspiracy theorists and marginalised investigative journalists. It wasn’t until NSA records were declassified in 2005 that it was finally confirmed that information regarding the incident had been distorted to give America a smoking gun to invade North Vietnam. There will be a lot of fingers pointed during the course of the Syrian war, but the fog of war is still creating confusion and it may not be until years after the dust has settled, and many more lives have been ruined and lost, that it will finally be able to proved who did and who didn’t have chemical weapons in Syria.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.