The collapse of the 'Moroccan exception' myth

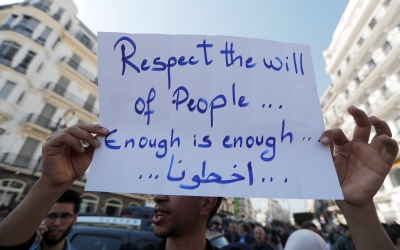

"Long live the people" and "Corrupt state," shouted the crowds of demonstrators gathered in the streets of Rabat, the Moroccan capital. Thousands of protesters recently rallied for the liberation of political prisoners, in a movement launched by the Hirak prisoners' families collective.

The population of the mountainous northen region, the Rif, was shocked when an appeals court last month upheld prison terms of up to 20 years for dozens of Hirak activists. Protest leader Nasser Zefzafi, inside Oukacha prison, sewed his lips shut to denounce the verdict.

Fearing social unrest, the Moroccan state was forced to allow the march to take place.

At the dawn of a new Arab Spring, Morocco is going through a major political crisis. The king is starting to become the focus of sharp criticism, especially on social media, something that was extremely rare in the past.

Increasing criticism

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Because of their geographical proximity, Moroccans are keenly aware of what is happening in neighbouring Algeria, where an anti-government uprising seems to have revitalised the country's social movements.

The protesters in Rabat were denouncing hasty political trials, which go against the official rhetoric of democracy and resilience in the face of the Arab Spring. The "Moroccan exception" theory put forth by regime loyalists, including some Western chancelleries, no longer stands up to the scrutiny of social reality.

In the face of an unsustainable political climate, the regime and its affiliates stubbornly persist in portraying Morocco as a haven of peace and political stability

At the heart of the political establishment itself, critical voices are increasingly being heard. They denounce the system's excesses and shortcomings, even if they do not dare to openly target the monarchy.

"Morocco is in the middle of a confused situation that affects all social categories ... We also notice a backsliding against the major changes undergone by Morocco since the early 2000s and the 2011 Constitution,” former socialist minister Nabil Benabdallah said, according to a March report in Akhbar al-Yaoum.

In the face of an unsustainable political climate, the regime and its affiliates stubbornly persist in portraying Morocco as a haven of peace and political stability in the region.

In 2011, the monarchy's proactive manoeuvres were instrumental in containing protests; a revised Constitution was approved by 98 percent of voters after a referendum waged through official propaganda. Authorities did not even shy away from mobilising mosque imams to encourage favourable votes.

A new Arab Spring?

Morocco is now being exposed to a wave of protests that may signal a new Arab Spring, including demonstrations that led to the spectacular eviction of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan and the forced withdrawal of Abdelaziz Bouteflika in Algeria.

But while Sudan and Algeria are authoritarian, military regimes, Morocco remains an enigmatic hybrid: a hereditary monarchy that closely supervises cautious democratisation efforts.

A careful examination of Morocco's political situation highlights the symptoms of an imminent uprising, similar to the ones in Sudan and Algeria. It is safe to say that social protests will increase, even if they currently appear to be sporadic and intermittent.

Several factors bring Morocco closer to this type of unrest, including the ongoing socioeconomic crisis, the weakening of the legalist Islamists of the PJD (the Justice and Development Party, which heads the coalition government), the disgrace hitting the judiciary after the arbitrary sentences against Hirak activists, and the curtailment of free expression and association.

Another factor is the vulnerability of the security apparatus, which is trying to violently repress peaceful demonstrations.

Among the decisive factors behind popular uprisings, three are worth highlighting: the withdrawal of the "mediating elites," including local elected representatives, trade union leaders and NGOs; identity conflicts, such as the conflict over Amazigh (or Berber) language and culture; and the disproportionate use of police repression, which can ultimately bolster the protest movement.

Seizing the opportunity

These three mechanisms are already operational, to varying degrees. All it would take would be a catalyst, such as the death of a Rif leader on hunger strike, for the movement to be revived. This confluence of factors could at any time lead to an outbreak of violent social unrest.

Which actor will seize the opportunity to establish power and use these factors for his own benefit? With a new Arab Spring on the way, the regime is wavering under the heavy pressure of mass protests.

By embracing repression - both police and judicial - King Mohammed VI has put an end to a myth that he personally strove to create: the "Moroccan exception". This makes the scenario of a violent popular uprising more and more conceivable.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This is adapted and condensed from a piece that originally appeared on the MEE French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.