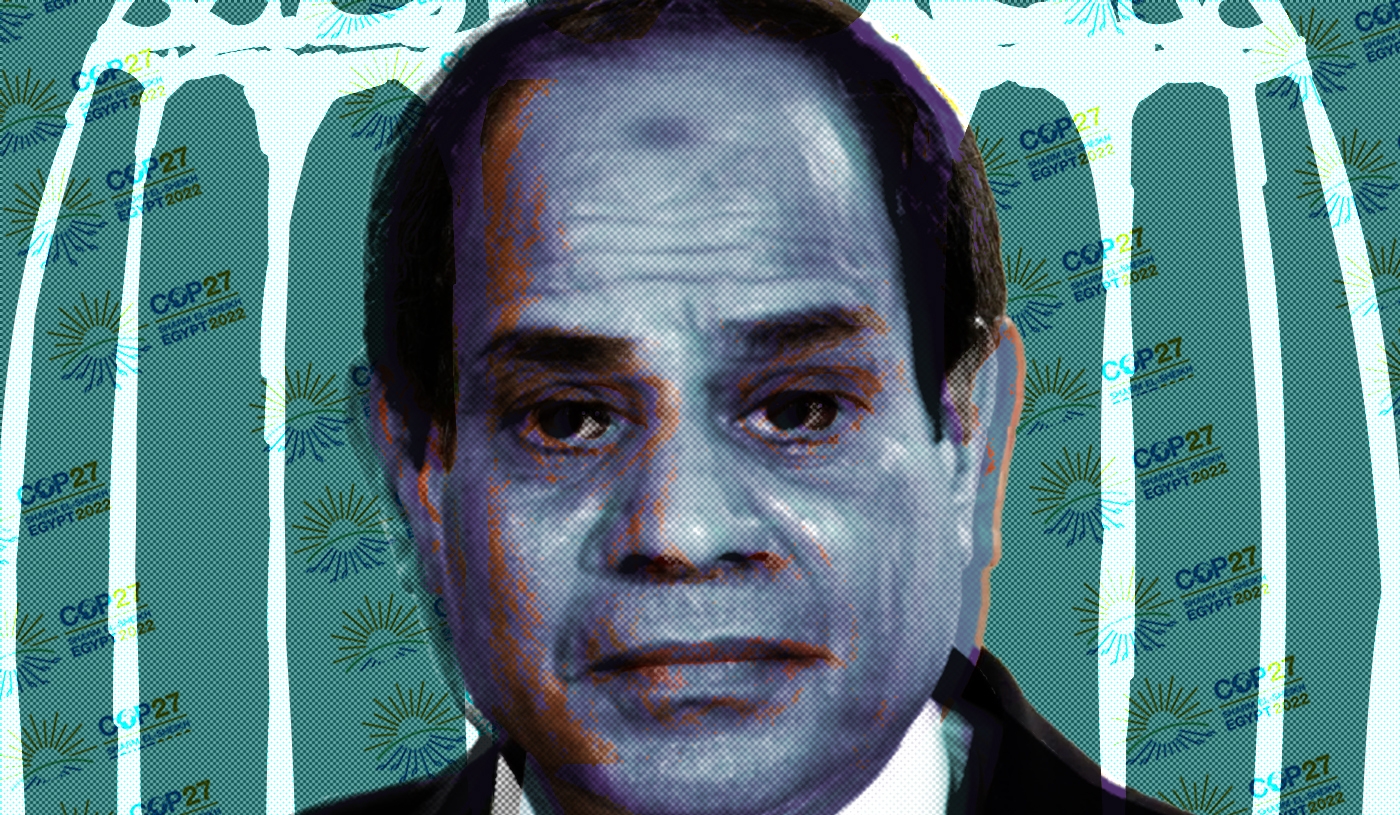

Cop27: How the climate crisis and resistance to Sisi's autocracy are linked

In January 2011, Tahrir Square teemed with revolutionaries demanding the resignation of Egypt’s then-president, Hosni Mubarak. A surging sea of young people, armed with banners and chants, transformed the polluted roundabout into a site of radical participatory democracy.

“There was this overwhelming dream and expectations of what could be done,” Samar Elhusseiny, a human rights activist in exile, told Middle East Eye. “It was a moment where every topic was on the agenda. There were discussions about the climate crisis, there was a space for everything … and there was a window to do something about it.”

Egypt will roll out the red carpet for international NGOs, while Egyptian activists will be conspicuous by their absence

That window slammed shut under the authoritarian regime of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who seized power in a 2013 coup and became president in 2014. With his rise, public engagement with the climate crisis has fallen. In a symbolic shift, as the revolutionaries from Tahrir Square were packed into prisons, the roundabout once again became choked with traffic and gas fumes.

During the eight years of Sisi’s rule, emissions have skyrocketed, the largest coal-fired power plant in Africa has been constructed, and unbridled development has resulted in trees being razed to make way for roads.

In How to Blow Up a Pipeline, author Andreas Malm highlights the extent of Egypt’s current environmental precarity.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“It is extremely vulnerable - the rising sea penetrating the Delta and spoiling fields with salt water; the summer heat growing insufferable in Cairo; the harvests in Upper Egypt predicted to shrink faster than in most breadbaskets … and yet the climate question is all but dead,” Malm writes.

Anti-autocracy struggles

His book aims to galvanise the environmental movement to escalate its tactics by using sabotage as a tool, rejecting the notion of “strategic pacifism”. He cites a number of examples of such tactics, from the suffragettes’ arson campaign, to the radical flank of the US civil rights movement, to the sabotage of power stations by opponents of South Africa’s apartheid system.

He also draws upon anti-autocracy struggles across the Middle East, comparing the scale of the Arab Spring mobilisations to the demands of the climate crisis, and the dictatorships that protesters sought to topple to the immutability of the fossil-fuel economy.

The toppling of Mubarak was whitewashed by pacifist-revisionist history, Malm says - but millions of Egyptians “did not reach the square by offering flowers to the police”. Police stations were ransacked and 4,000 of their vehicles destroyed. This “opened the sluice gates of the Nile” and invited people to join the movement in Tahrir Square.

Throughout 2011, the pipeline carrying gas from Egypt to Israel was repeatedly attacked, precipitating the cancellation of their bilateral gas deal. But while Malm recognises the long history of pipeline sabotage as a tool of resistance against occupation and autocratic regimes in the Middle East, he questions why these climate-harming pipelines were not targeted “as destructive forces in and of themselves”.

Indeed, for a region “crisscrossed with fossil fuel infrastructure”, and one that has a disproportionate vulnerability to climate change, there are few historical examples of climate action in the Middle East, Malm notes.

Egypt is an instructive case. Despite the raft of environmental problems that it is grappling with, activists must weigh the heavy risks of arrest - or worse - before speaking out.

In 2017, Elhusseiny says she was allowed to leave the country to pursue her master’s degree - and she never returned. Many others were not as lucky, with an estimated 60,000 political prisoners in Egyptian jails, and sweeping laws banning protests and the spreading of “false news”. NGOs face asset freezes, while collaborating with international groups can lead to prison time.

Smoke-and-mirrors act

Amid this backdrop, Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh next week will be an elaborate smoke-and-mirrors act, carefully stage-managed by the Egyptian government in an attempt to greenwash its human rights record and position itself as the “voice of the Global South”.

Egypt will roll out the red carpet for international NGOs, while Egyptian activists will be conspicuous by their absence, having been sidelined, defunded or put behind bars. The international NGOs who attend will be complicit in this theatre.

That’s why the Egyptian Human Rights Forum, for which Elhusseiny now works as a communications officer, has issued a petition urging Egyptian authorities to address the country’s human rights crisis ahead of the climate conference. “We emphasize that effective climate action is not possible without open civic space,” the petition notes. “As host of Cop27, Egypt risks compromising the success of the summit if it does not urgently address ongoing arbitrary restrictions on civil society.”

While some in the international community might fail to see the link between the climate crisis and Egypt’s systematic crackdown on civic space, Elhusseiny says the connection is stark: “You cannot make a wide impact on anything without giving the people the space to express their ideas.”

In his book You Have Not Yet Been Defeated, Egyptian activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah, who has been in prison for most of the past decade, recalls how the Freedom Charter was collaboratively written with the help of 50,000 volunteers who gathered input from people across South Africa on how they wanted their country to be run. Their patchwork of answers made up the new constitution.

It was this type of participatory politics that young Egyptians sought in Tahrir, and later in the drafting of the constitution.

“What would happen if tens of thousands of people were involved in assembling this dream? … We might find priorities that have been overlooked,” Abdel Fattah writes, adding that perhaps “if we listened to the fishermen on our lakes and heard their complaints about the destruction of fisheries by multinational corporations, we’d discover how urgent this issue is, how it’s linked to social justice and in need of constitutional protection”.

'Don't stop fighting'

Through their writing, both Malm and Abdel Fattah are pleading for activists to resist despair. The title of Abdel Fattah’s book is ambiguous, containing both an inkling of defeat and a reason for hope. “All that’s asked of us is that we don’t stop fighting for what is right,” he wrote.

With momentum building for Cop27, the window for change that slammed shut after Egypt's 2011 uprising has opened a crack

As Malm adopts a narrow vision of climate resistance in the Global South, numerous examples of sabotage as resistance in the Middle East do not satisfy his criteria, as the motivations were divorced from a commitment to ending fossil-fuel capitalism.

But this view does not recognise the debt owed by movements in the Global North to the revolutionaries of Tahrir now languishing in prison.

“You can draw a pretty straight line from Tahrir to Occupy, to Bernie Sanders’s 2016 US presidential campaign, to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s election to Congress and her championing of the Green New Deal,” analyst Naomi Klein noted in an article for the Intercept. Other movements have drawn inspiration from the youth of Tahrir precisely because their occupation was an affirmation of life.

With momentum building for Cop27, the window for change that slammed shut after Egypt’s 2011 uprising has opened a crack, shedding light on the threads connecting those languishing behind bars with the climate crisis - and the international community would do well to take heed of this link.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.