Israel is using coronavirus to implement the deal of the century

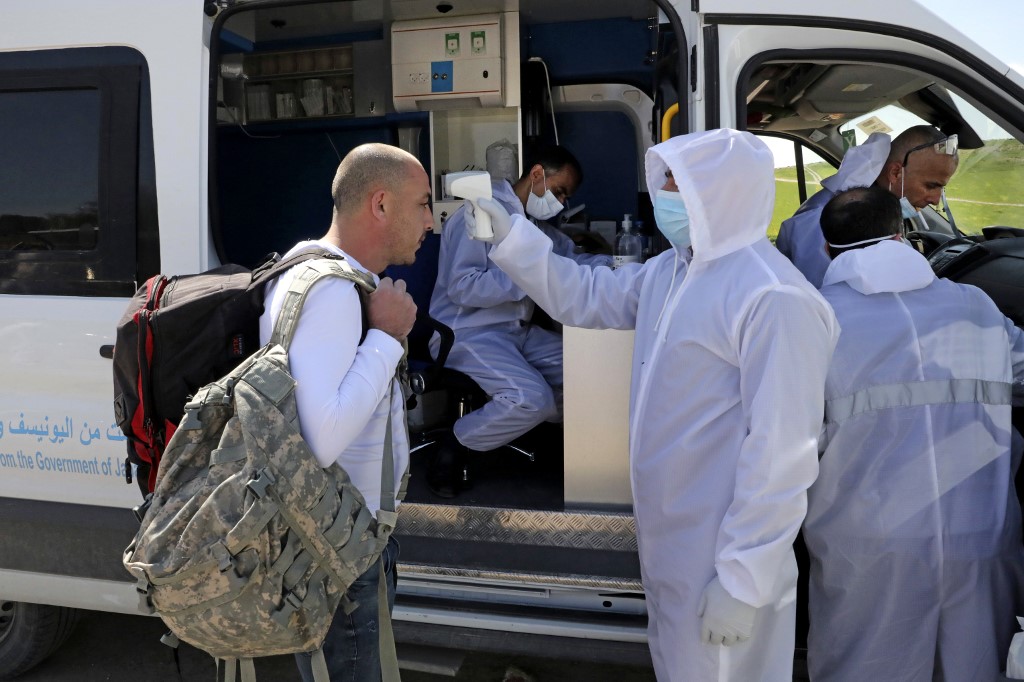

The global spread of coronavirus has necessitated movement restrictions around the world, including in Israel and Palestine.

As the occupying state, Israel controls all entrances to and exits from the occupied West Bank and Gaza. Last week, it closed off Palestinian-administered areas under the pretext of “limiting the spread” of coronavirus. Bethlehem has been fully locked down for weeks.

It is clear to Palestinians that Israel is taking advantage of Covid-19, exploiting the West Bank lockdown to accelerate the annexation of Palestinian land, while allowing Israeli settlers to attack Palestinian civilians - further complicating Palestinian efforts to combat the pandemic.

Movement restrictions

The Israeli army is using the pretext of coronavirus to impose further closures and movement restrictions on Palestinians. This ought to be a matter of public health, and the restrictions should apply equally to Israelis, as anyone can get infected - but the Jewish settlers in the occupied West Bank, who live just a few hundred metres from the locked-down Palestinian communities, are not facing the same restrictions.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Israelis apparently believe they can take advantage of the current situation to implement the US “deal of the century”. Israel’s imposition of restrictions on movement in bantustan-like Palestinian areas is an early warning of how things would work if US President Donald Trump’s deal were to be implemented.

The current restrictions could cause serious problems for chronically ill Palestinians, including my daughter

For me, as a Palestinian born and raised under the Israeli occupation, the new ban on movement brings back memories of the curfews and siege imposed by the Israeli occupation on the Palestinian territories, especially during the Second Intifada, under the pretext of security.

During that time, the Israeli army locked down Palestinian communities and turned our lives into an unbearable nightmare, subject to severe repression.

In 2002, in my hometown of Qira in the northern West Bank, my newborn daughter Lina got a viral infection that caused severe diarrhea and fever for several days - but we couldn’t take her to a hospital or doctor, due to the Israeli-imposed curfew.

A year later, we discovered that this untreated infection had caused chronic kidney failure, and a kidney transplant was needed to save her life. The current restrictions could similarly cause serious problems for chronically ill Palestinians, including my daughter.

Collective punishment

So far, more cases of coronavirus have been reported in Israel than in the West Bank. More than 2,500 cases have been recorded in Israel, compared with fewer than 100 in the Palestinian territories. Yet, despite the unprecedented health crisis and widespread social isolation measures, Israeli police “have chosen now, of all times, to escalate their abuse and collective punishment” of Palestinians in East Jerusalem, according to the human rights group B’Tselem.

The level of violence perpetrated by Jewish settlers has simultaneously increased, with reports citing a campaign of attacks against Palestinian shepherds and farmers. In the Bethlehem area, where Palestinians live under strict quarantine, settlers recently uprooted hundreds of trees belonging to Palestinians.

The Israeli army also recently allowed Jewish settlers into an archaeological site in the village of Sebastia in the northern West Bank, despite a Palestinian Authority decision to close down tourist sites and ban gatherings in an effort to fight the coronavirus outbreak.

In the meantime, Israel has started building roads for settlers near my home village south of Nablus - a clear attempt to define bantustans and ghettos for Palestinians. The settlers, under the protection of the Israeli occupation army, do not miss an opportunity to cause more suffering to the Palestinian people, using various pretexts and excuses.

In Gaza, which has registered just a handful of cases of coronavirus, there are serious concerns over the capacity of the healthcare system, which was already in crisis due to the Israeli-imposed blockade.

Dirty and overcrowded prisons

Israeli authorities recently reported that four Palestinian prisoners had been infected with coronavirus in an Israeli prison, after contact with an Israeli investigator who had Covid-19.

More than 5,000 Palestinians, including women and children, are currently being held in Israeli prisons, which are notoriously old, dirty, overcrowded, and lacking in basic hygiene supplies. If Israel cares about prisoners’ safety, it should release them.

In 1991, during the First Intifada, I was arrested by the Israeli army at the age of 17. Investigators tortured me for 39 days, using all means of physical and psychological torture. I witnessed firsthand the solitary confinement conditions in a very tiny, dirty cell without windows; my health was neglected.

Palestinians today are trapped and fighting on two fronts: one against the pandemic, and the other against Israel’s brutal military occupation.

Yet one positive outcome of the recent lockdown is that it may draw attention to the daily movement restrictions that are omnipresent in Palestinians’ lives, but which most of the world doesn’t care about, or even know to exists.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.