Counter-revolution in the 21st century: How elites are crushing dissent

History does not move in straight lines, but in waves - some gentle, others swelling in great crests. And after each wave, there is almost inevitably a crash.

In recent times, waves of uprisings have swept different regions of the world, shaking the established order. As in the past, revolutions, or insurgencies that threaten the political and social power structure, are invariably followed by a reaction.

Three regional uprisings in the last decade, North Africa and the Middle East; Latin America; and the West, each peaked in the period 2018-22. For the purposes of this article, I will focus on this recent wave of uprisings rather than those of 2010-12.

In the Mena region, Algeria, Sudan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Iran all witnessed mass, popular, and mostly peaceful protests, even in the face of state violence, indicating significant political learning from the earlier uprisings that evolved into armed insurgencies in several countries.

At least initially, these movements achieved partial success: regimes responded with violence, but the discredited leaderships were in some cases removed, in Algeria, Iraq, and most decisively Sudan; political corruption was dealt with in the courts, and some former rulers and ministers were jailed.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In Iran, no quarter was given, although the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement of late 2022 did achieve limited gains - at a high cost of hundreds killed - in terms of loosening the rigid Islamic regime dress code.

Yet after a period of time, the protests ran out of energy, and the deep state was able to reassert itself and crack down on protesters. Normal business was resumed.

Uprisings

In Latin America, popular uprisings took place in Chile (2019), Colombia (2021), and Peru (2022), and in several countries, the left came to power after a 50-year struggle, involving protracted civil war, mass repression, and military coups.

The achievement of these mass struggles can’t be underestimated, given the history of US interference and violence in the continent, including recent judicial coups, such as in Bolivia in 2019 and the CIA "gift" to Brazilian prosecutors in the 2018 arrest of now president Ignacio Lula da Silva.

In the West, significant uprisings were seen in the US in 2020 following the police murder of George Floyd, and in France, first with the Yellow Vest movement of 2018-19 and then in early 2023 against Emmanuel Macron’s pension reform, probably the most significant protest movement France has seen since 1968.

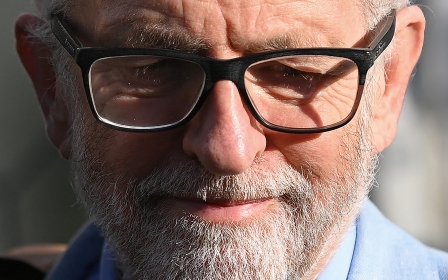

Political insurgencies were seen in the UK, with Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn, and in the US with Bernie Sanders’ two attempts at winning the Democratic nomination for president.

Both of these movements were defeated, and in the case of Corbyn, he was removed from the party he led under a spurious process orchestrated by his successor. But the resonance of mass mobilisation, and the recent strike wave across UK public services, is yet to fully play out.

Counter-revolution

This brings us to the establishment reaction. Conventionally, counter-revolution is a response to a mass uprising or the seizure of power by socially excluded groups or classes.

The ruling class, facing a serious - even existential - threat to its rule, must reorganise and strike back against the insurgent political forces. This occurs even if the insurgents are following the “rules of the game” by participating in elections or in peaceful, legal protests (hence Lenin’s contempt for bourgeois parliamentary socialism).

6 January 2021, and a recent German far right plot, however doomed each event was, marks a new kind of willingness to reject constitutional order

Antonio Gramsci wrote in 1930 that the bourgeoisie, when in great danger, can attempt to solve “a historico-political situation characterised by an equilibrium of forces heading towards catastrophe” through the intervention of a “great personality” tasked with the “arbitration” of the conflict at hand.

In recent times there has been an abundance of such figures: Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, and Boris Johnson, to name a few.

In Sudan, arguably such a "Bonapartist" figure was Omar Bashir, and following his downfall in 2019, a catastrophe happened. The military carried out a coup against the civilian reformist movement in 2021, before its two major factions fell out in a battle for spoils and power, sparking a bloody conflict.

In Tunisia, the president imposed authoritarian rule in a kind of would-be populist coup that lacked any legitimacy - or popularity. His only strength was the failure of the liberal politicians that he overthrew to give Tunisians any hope for the future following the 2011 revolution.

Latin America and the West

In Latin America, counterrevolutionary forces have been mobilising, from Chile, where a leftist student leader was elected following the uprising, northwards to Peru and Colombia, where insurgencies and unprecedented electoral outcomes overturned decades of neoliberal orthodoxy.

The new Peruvian president Pedro Castillo was removed last year in a judicial coup following months of political sabotage by the rightwing congress. He was arrested and jailed, accused of "rebellion and conspiracy". Protests in the wake of his arrest by thousands of supporters from the poor Andean community were met with deadly violence.

In Colombia, a year after the election of the country’s first left-wing president, the establishment, including military veterans, is making concerted moves against the new government, while a steady drip of murders of activists has continued despite a historic peace agreement.

In the West, the idea of coups or violent crackdowns may seem outlandish, or it did until recently: the riot of 6 January 2021, and a recent German far-right plot, however doomed each event was, mark a new kind of willingness to reject constitutional order.

For now, the ruling US political and financial elite is secure, and the left and grassroots movement is weak and fractured. Whether under Biden centrism or a return to Trump's populism in 2024, the rich are safe.

In the US, counterrevolution has a permanent character: the CIA and State Department orchestrate it abroad; at home, it’s the job of the FBI, local militarised police forces, and a corporate-controlled Congress.

A new McCarthyism

The picture in Europe is a little different. A scourge has been identified and the charge is antisemitism. The scale of misinformation and hysteria being whipped up against dissenters, such as singer Roger Waters, is on a level rarely seen in modern times.

This is not genuine antisemitism, which is on the rise, but a manufactured kind used to target opponents of the establishment, with little or no regard for facts or truth.

The US anti-communist witch-hunts led by Senator Joseph McCarthy in the late 1940s and 50s are the most obvious parallel to the spurious allegations against politicians, artists, and filmmakers, like the UK’s Ken Loach.

Antisemitism is also the centrepiece of one of the most virulent and relentless campaigns in the West - that inside the Labour Party against anyone opposed to party leader Keir Starmer. Each day brings new candidates blocked or suspended, and new allegations that don’t stand up to scrutiny.

His is the most factional, intolerant mainstream party regime the UK has ever seen. He is lucky that the UK media is complicit in his campaign to liquidate the left of his party so that he can become prime minister of a tame, pro-business government.

If Starmer does win the UK election in 2024, we should expect his authoritarian approach to dealing with dissent in the country to be at least as harsh as the Conservatives. And he will have unprecedented powers of repression at his disposal.

The UK government, since Brexit, has passed a panoply of draconian anti-protest laws, including the notorious Public Order Act and Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act.

These are not just on paper: police swept up peaceful anti-monarchy activists, and even a monarchist bystander, on the day of King Charles’ coronation. Climate protesters and pro-Palestine activists have faced much harsher sentencing. Starmer has largely approved.

France this year has witnessed months of violent clashes between riot police and protesters following the forcing through of unpopular pension reforms. A French publisher was arrested and interrogated by British police under counter-terrorism laws about his attendance at protests and his political beliefs.

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, meanwhile, remains in Belmarsh prison awaiting extradition to the US, with UK judges upholding his extraordinary detention.

This is Britain and France, not Russia.

Far-right populism

Even in Germany, where one centrist coalition led by Angela Merkel was replaced by another led by Olaf Scholz of the Social Democrats, a cranking up of repressive policies towards climate campaigners and pro-Palestine activists has been orchestrated, with allegations of antisemitism part of an ongoing campaign of delegitimisation and bans.

In a period of massive inequality, war, inflation, and escalating climate breakdown, it is hard to know how long this wave of reaction can last, or where it will end.

The more repression and politico-media campaigns against dissenters we see, the more it feels that the ruling regimes share one emotion: fear that they could lose control.

Waiting in the wings, and already sharing power in Scandinavia, Italy, and central Europe, are the right-wing populist parties; the new “respectable” face of neofascism.

This political movement, already co-opted by Britain’s Tories and US Republicans, is the last resort for state-corporate power if traditional neoliberal parties, or centrism, fail to restore stability.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.