‘De-escalation’ in Syria: Another doomed ceasefire attempt

If it looks like a ceasefire attempt and sounds like a ceasefire attempt, it must be a ceasefire attempt.

But one can see why the primary diplomatic brokers regarding the conflict in Syria are so reluctant to call a spade a spade. Ceasefires in Syria have a bad reputation because they have failed from their outset.

Rather than address their failings to come up with a proposal more likely to succeed, the brokers have simply repackaged the same faulty product

But rather than address their failings to come up with a ceasefire proposal that is more likely to succeed, the brokers have simply repackaged the same faulty product. Last year saw the ill-fated “cessation of hostilities,” along with unconvincing denials that this was the same as previous ceasefires.

Now there is a new term for the same thing: “De-escalation.” The false advertising should fool no one.

Last week’s signing by Russia, Turkey and Iran of a deal to establish four “de-escalation zones” in Syria will fail for the same reasons as the “cessation of hostilities” and all previous ceasefires: they share the same fundamental flaws.

So little zoned

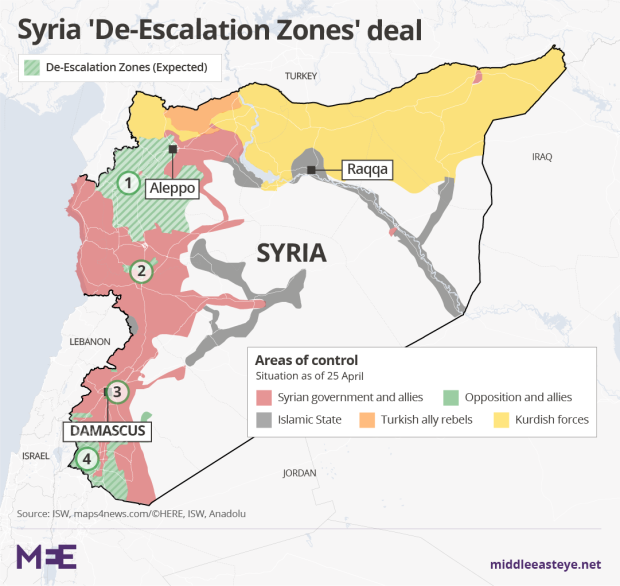

The vast majority of Syria is not covered by the zones. The swathes of territory in the centre and east held by the Islamic State (IS) are excluded, as is the huge stretch of the north controlled by the Kurds, who in any case have condemned the plan as a “sectarian partition” of the country.

Only a minority of rebel- and regime-held territory is covered. In fact, it is striking to see on a map how little of Syria is included.

If Moscow, Ankara and Tehran feel that such a small scope will heighten the likelihood of success and lead to the zones’ expansion or the creation of new ones, the opposite is more likely. Developments in the rest of Syria, where it will be war as usual, are more likely to affect the success or failure of these zones.But even these limited areas will not be insulated from the conflict. The Syrian regime, while officially accepting the proposal (though not a signatory), has in its usual fashion included caveats that render it meaningless.

Foremost among them is that it will continue to go after “terrorists”. Since it deems all rebel groups terrorist, it is still technically open season on them.

Damned if you do, damned if you don't

For their part, some rebel delegates stormed out of the signing of the deal, rejecting it because of Iran’s inclusion. Meanwhile, Russia says it will continue to target IS, but since its direct intervention in Syria in 2015, Moscow has used this pretext to primarily target rebels.

Rebels face the dilemma of being attacked if they do not separate from al-Qaeda-linked groups or being attacked by the latter if they do

Groups linked to al-Qaeda will also continue to be targeted, but they have not been specified, raising the possibility of differing – and convenient – interpretations according to a party’s goals and interests.

As with past ceasefires, Moscow says this proposal gives rebels the opportunity to separate themselves from al-Qaeda-linked groups on the ground. That is far easier said than done – as Russia knows, rebel forces are either intertwined or in close proximity to each other, often in confined areas, making it near-impossible to separate them.

Who is policing this?

Given all this, unsurprisingly heavy fighting and regime air strikes have taken place from day one of the deal, just like its predecessors.

The regime has crippled the possibility of independent monitoring by denying the UN any role

Accusations have been traded over who started it, which brings us to another fundamental failing of this and previous proposals: lack of a monitoring mechanism to stop violations, without which there is no impediment to them.

The regime has crippled the possibility of independent monitoring by denying the UN any role. It also rejects the idea of foreign forces patrolling the zones – this would obviously exclude its primary allies Russia and Iran, but what of the deal’s third guarantor, Turkey?

► READ MORE: There is a clear alternative to Assad. To say otherwise is nonsense

The regime has long condemned the presence of Turkish forces in Syria, so what it seems to envision is monitoring solely by its allies, just as in the last sham presidential election. Even if Turkey was involved, this would hold the monitoring mechanism hostage to claims and counter-claims by parties that back different sides in the conflict.

The ultimate flaw

Another fundamental flaw is that “de-escalation,” like its predecessors, is not linked to a viable peace process, without which any ceasefire is doomed.

What is the point of this plan? It seems to be another attempt by Moscow to side line the US and UN on Syria and assert its dominance

The current attempt is tied to the Astana process launched by Russia and Turkey in December 2016, but it has made no tangible progress. This is unsurprising because it is a replica of the ongoing Geneva process but under different stewardship, despite the fact that the latter has floundered for years.

The biggest flaw in both tracks is that they have actively avoided tackling the core issue: the fate of Syrian President Bashar Assad, whose dictatorship and brutal response to peaceful protests sparked the war, and whose regime is responsible for the vast majority of deaths, displacement and destruction.

So what is the point of this plan? It seems to be another attempt by Moscow to sideline the US and UN on Syria and assert its dominance over events on the battlefield and at the negotiating table.

It is also a means for Russia and Turkey to consolidate their rapprochement by working together, no matter how futile the effort. And it legitimises Iran as a key player diplomatically and militarily. In other words, “de-escalation” is for the benefit of its guarantors, not the Syrian people.

- Sharif Nashashibi is an award-winning journalist and analyst on Arab affairs. He is a regular contributor to Al Arabiya News, Al Jazeera English, The National, and The Middle East magazine. In 2008, he received an award from the International Media Council "for both facilitating and producing consistently balanced reporting" on the Middle East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Syrian government forces' MiG-23 fighter-bomber drops a payload during a reported air strike in the rebel-held area of Qabun, east of the capital Damascus, on 6 May 2017 , the day after the de-escalation deal came into force (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.