The disease of liberalism in the Arab world

The major struggles in the Arab world today - in Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, Sudan, Morocco and elsewhere - are struggles against neoliberal economics and the poverty and repression it has wrought.

These are struggles for economic democracy and against economic dictatorship, to liberate people and free them from poverty. This augurs badly for the political, economic and intellectual elites who have supported and benefited from this system at the expense of the majority of the Arab peoples.

How did the situation in the Arab world become so dire, especially as from the 1950s to the 1970s, all major economic indicators showed huge accomplishments that have since dissipated?

Economic independence

Whereas this early period was dominated by the progressive ideals and policies of national liberation, today’s dominant discourse is that of liberalism. Both liberation and liberalism derive from the word liberty, but in the colonial and postcolonial Arab world, as elsewhere, the two terms have had varied histories, goals and achievements.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

One could divide their intellectual, cultural, political and economic effects between the periods immediately following independence in the 1940s through the mid-to-late-1970s, and the period between the 1980s and the present.

The first period was informed by the ideals of national liberation, which dominated popular political movements and elite intellectual trends, while the ideals of liberalism inform the second period and dominate the fields of elite intellectual production and political activism.

The principles of national liberation were delegitimised in favour of a new language characterised by liberalism

From the 1950s through the 1970s, Arab intellectuals and political movements supported the project of liberation from colonialism and the achievement of not only political, but also economic independence.

The language of national liberation became the rallying cry of recently decolonising regimes, spearheaded by former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser but encompassing both Syria and Iraq, and overtaking even conservative regimes in Tunisia and Jordan, and anti-colonial movements from Algeria to Palestine to Oman and the rest of the Gulf region.

The goal of economic democracy, viewed as partial redistribution of wealth and state-led development aimed at closing the income gap and ending poverty, was paramount during this period.

Gradually following the 1967 war, and increasingly by the mid-to late-1970s, the principles of national liberation were delegitimised in favour of a new language characterised by liberalism, wherein liberals came to depict national liberation as oppressive, suggesting that all it had brought about was political dictatorship, and economic and military disasters.

Personal freedom

Liberalism, in contrast, promised to bring about personal freedom, regional peace and individual prosperity, as well as political democracy, through “free” elections.

As this phase of Arab liberalism emerged with the onset of neoliberal economics, post-1970s Arab liberals, like liberals elsewhere, dismissed economic democracy as contrary to the "freeing" of opportunities for personal enrichment, even if some criticised the excesses of neoliberal economics and sought to mitigate their effects.

If the project for national liberation was based on the notion of popular, plebiscitary political democracy as the companion to economic democracy, liberalism now insists on an electoral “representative" democracy that ensures economic dictatorship, insofar as the market should dictate economic policy and not the people or the state institutions representing them.

The political goals of national liberation were not unique to the Arab world. They were shared with many of the decolonising countries in Asia and Africa from the 1950s through the late 1970s. Nor was the adoption of the values of Western liberalism, which began to dominate the Arab world in the late 1970s onwards, an isolated phenomenon, but one that was also shared across Asia, Africa and Latin America, let alone Eastern Europe, after 1990.

The advent of national liberation and socialism in the Arab world coincided with the convening of the Afro-Asian conference at Bandung in the mid-1950s, and of the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement soon afterwards, followed in the mid-1960s by the Tricontinental Conference in Cuba, which globalised this quest against colonial and neocolonial powers.

The project in the Arab context led to an attempt at unity and federations between Arab countries - attempts that were also ongoing between sub-Saharan African countries led by Ghana, and the recently decolonising Caribbean nations of the West Indies.

Imperial machinations

While the project for federation and unity was fought vehemently by the US and defeated in all three contexts by 1963 due to a combination of imperial and internal factors, the launch of “Arab socialism” proceeded apace with impressive economic and political results, which aimed at delinking the local economies from imperial machinations.

The presence of the Eastern Bloc was most helpful in staving off, for awhile, attempts at imperial restoration of the status quo ante. The staving off, however, would ultimately fail.

Beginning with the anti-Mosaddegh coup and the restoration of the Shah in Iran in 1953, the overthrow of President Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954, and the ousting of Prime Minister Suleiman Nabulsi of Jordan in 1957, imperial coups toppled Indonesia’s Sukarno, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba, and Brazil’s Joao Goulart, among others, in the 1960s.

Unlike Arab socialism, the new liberalism and neoliberalism articulate their goals in terms of individual, not collective, identities

The attempt to oust Nasser faltered, though Israel, at the behest of the US, dealt the coup-de-grace to his regime with its invasion and defeat of the Egyptian army in 1967. His death in 1970 marked the beginning of the end of the era of independence and national liberation.

During the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, not only did Arab “socialist” economies skyrocket to unprecedented levels, but infant mortality declined measurably, socialised healthcare for the population at large became available, increased life expectancy and more equal income distribution were achieved, and land reform programmes and investment in heavy industry transformed the local economies in unprecedented ways.

These achievements were made, as author Ali Kadri has shown, despite the ongoing imperialist threat and the war tensions with Israel that resulted in large military budgets, which limited but did not sacrifice social and economic goals.

War and peace

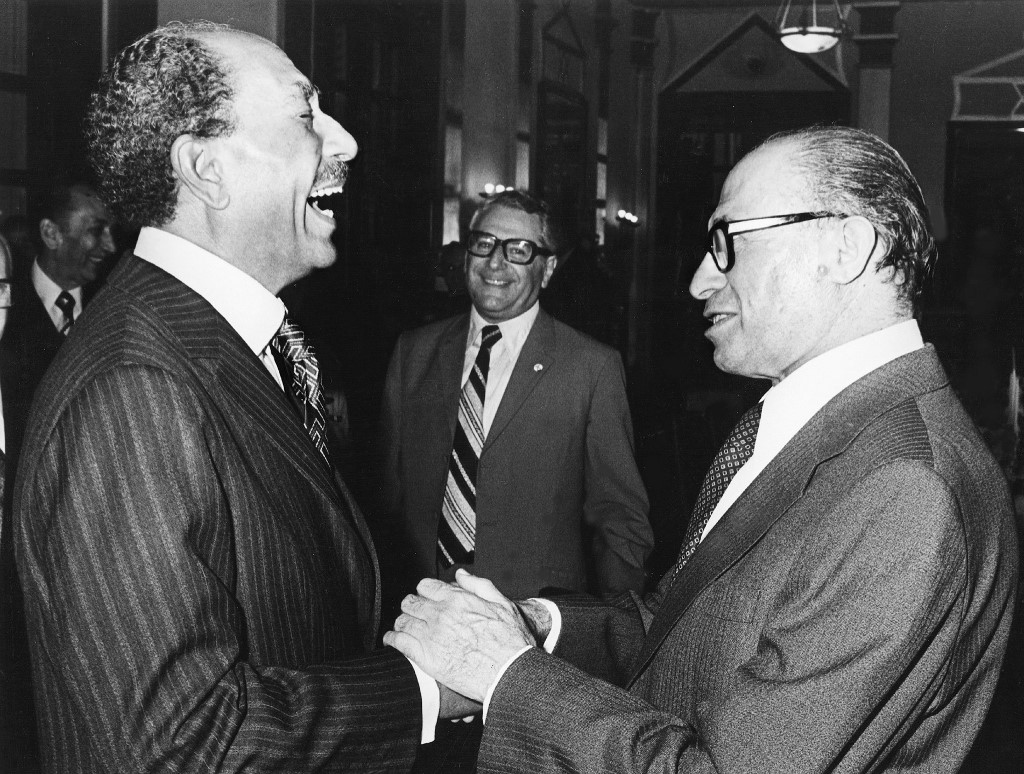

With the rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s and its consolidation in the 1980s onwards, all of this changed economically, but also politically and culturally. That the Camp David Accords formalised this transformation was hardly coincidental.

In that context, and with the waning influence and subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union, the same political forces that had played a progressive role committed to national liberation and social and economic justice in the previous period switched alliances to the new local economic elites - a new class of liberal intellectuals and their imperial sponsors, all committed to social inequality and economic dictatorship.

Increased poverty for the majority and immense wealth for the elites were the immediate and lasting results

In the period following the 1967 war, liberals argued that the state of war with Israel drained state resources, while peace would enrich all Egyptians, indeed all Arabs.

The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, whose liberal transformation and disavowal of violence in the 1970s allowed it a seat at President Anwar Sadat’s table, joined the political contest on the side of the liberal secularists against the Nasserist political and economic legacy, and in favour of neoliberal capitalism.

By the late 1980s, the political and economic line the Egyptian regime and Egyptian liberals pushed was adopted wholesale by a new class of Arab intellectuals. Liberal and neoliberal Palestinian intellectuals and politicians promised that the US-sponsored “peace process” would transform the West Bank and Gaza into a new “Singapore”.

Jordanian liberals and neoliberals, in turn, predicted immense riches as a result of peace with Israel, concluded in 1994 alongside new neoliberal economic policies. In both cases, as happened in Egypt, increased poverty for the majority and immense wealth for the elites were the immediate and lasting results.

Spreading corruption

Unlike Arab socialism, the new liberalism and neoliberalism articulate their goals in terms of individual, not collective, identities; in individual political rights, not collective economic rights; and in condemning the history of the past and reinterpreting it as a liberal political and economic failure, rather than as a basis for a more economically and politically democratic future.

Whereas national liberationists delivered on their promises of free universal education and healthcare, partial redistribution of wealth and increased productivity, the neoliberal regimes that the liberal intellectuals supported or helped bring about have shut down political democracy, spread corruption, and reversed all previous economic achievements.

The infighting between secular and Islamist liberals has not been over questions of economic democracy, the right to education and free healthcare, or redistribution of wealth, but rather about political power in the service of neoliberal economics and over cultural policies.

Today, the majority of people of the region have lost most of their economic rights and, as a result of the betrayal of political democracy by the secular liberals who supported coups against Islamist liberals in Algeria, the West Bank and Egypt, gained no political rights or “human rights” in the interim.

Whereas national liberation under “Arab socialism” - despite its repression of liberal political rights - had freed people from economic dictatorship, poverty, illiteracy and disease, the new neoliberal regimes and their liberal intelligentsia have freed the Arab peoples only from Arab socialism and a decent standard of living.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.