'British values': Does anyone in the UK really know what they are?

A few months ago, when I spoke out in support of the right for British schoolchildren to pray during their lunchtimes (after news emerged that some had been banned from doing so), my social media mentions were inundated with racist abuse.

But that wasn’t the surprising part. I noticed that there were two clear camps: one insisting that schools in the UK are secular and should not accommodate prayers, and the other that Britain is a Christian country, so if I want to wear a hijab or use a prayer mat, I should go “back” to Saudi Arabia.

Reading through these messages, it became clear that even the most ardent defenders of British national identity actually have no idea what it is.

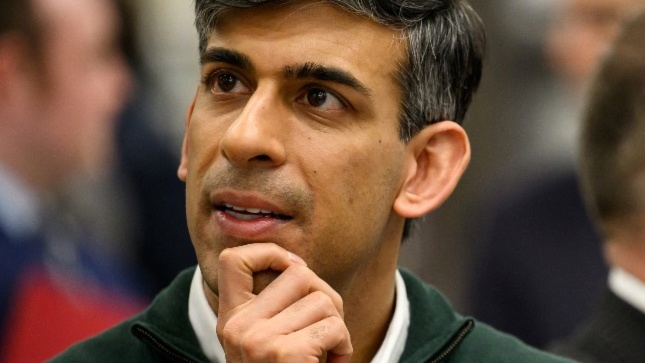

What’s ironic is that this comes at a time when “British values” are being emphasised more than ever in our political discourse. Consider Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s recent speech, in which he said anyone undermining British values was “extreme”; the resurgence of nationalist symbolism such as the Union Jack on Labour campaign materials; or the mass hysteria about Saint George’s Cross “going woke” on the new England football kit.

While a hollow, aesthetic nationalism surges, there is a disconnect on the ground, and even in our politics, about what the very nation state we are told to worship actually stands for.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

When we are reminded to revere Britain, what is it that we are celebrating? Is it secular? Is it Christian? Is it somehow a combination of both, like Richard Dawkins’ newfound “culturally Christian” identity? Nobody seems to know.

But consider some of the most contentious “culture wars” so far this year, each of which has evoked a renewed rallying cry for Britishness, and one common thread rises to the surface: Islam as the enemy.

Perceived threat

In fact, it seems as though Britishness today intrinsically relies upon the perceived threat of overt Islam, to which it casts itself in opposition. Whether the debate focuses on the role of prayer in schools, the displaying of an Islamic hadith at King’s Cross station, or the exhibition of Ramadan lights in London (including over Easter weekend), there is a prevailing notion that whether objections are based on secularism or Christianity, it doesn’t matter - as long as people push back against the presence of Islam in the public sphere.

In other words, to be British revolves around being the very opposite of Islam, rather than anything coherent or meaningful in and of itself.

To be British revolves around being the very opposite of Islam, rather than anything coherent or meaningful in and of itself

In an election year, this provides ammunition for individuals looking to bolster their own political platforms by riding the wave of normalised Islamophobia, taking advantage of the innate contention at the heart of Britishness itself.

The more figures such as former Home Secretary Suella Braverman, the politically ostracised MP Lee Anderson, or former Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage spew anti-Muslim sentiment in the media, including the oft-repeated claim that Islamists are taking over Britain, the more Britishness itself becomes defined by pushback against Islam - and not much else.

This has a tangible and visceral impact on the lived realities of British Muslims, who are already facing hate crimes and violent harassment in greater numbers than ever before: a 600 percent increase, in fact, since October.

British Muslims are already disproportionately disenfranchised and facing political homelessness due to the major parties’ stances on Islamophobia and Palestine. Now, we are set to be further pushed to the margins by this myopic view of Britishness, paving the way for a generation of even more disillusioned Muslims who have grown up in the UK, but absorbed the message that this isn’t our rightful home.

Most worrying of all is that disengagement will in turn fuel the nationalistic, anti-Muslim idea that we don’t integrate in Britain.

Antagonistic opposition

Dawkins’s recent comments about choosing Christianity over Islam, and his assertion that Islam is uniquely misogynistic in a way that other faiths are not - coupled with his past comments about how church bells sound so much better than the “aggressive” Islamic call to prayer - are telling. Such views suggest that Britain’s rejection of Islam is based on racist “Othering”, rather than an objection to values.

No matter how this debate is framed, and regardless of the superiority western values might try to assert over Islamic ones, the fact is that Islam has been conflated with extremism and anti-Britishness to the extent that perfectly innocuous displays of Muslimness become red flags - from twinkling lights on Oxford Street to an ITV documentary about Ramadan that was inundated with hateful comments even before it aired.

What’s more, even British Christianity seems to be defined by pushback against Islam, as evidenced by the archbishop of Canterbury’s refusal to meet (fellow Christian) Palestinian pastor Munther Isaac, a move he later backtracked on, or his decision not to block the government’s Rwanda bill, which would negatively affect Muslim migrants.

Indeed, nothing seems intrinsically British today that isn’t in antagonistic opposition to Islam.

The overriding irony in this discourse is that Muslims are monotheistic followers of an Abrahamic faith with a belief in the Bible and Torah as previously revealed texts from God, and a respect for fellow People of the Book. Ask any Muslim; we don’t relish the sight of empty church pews.

As much as we are unfairly blamed for the decline of Christianity (consider a recent Daily Mail headline that decried empty churches and overflowing mosques as a symptom of Ramadan “muscling out” Easter), the truth is that many of us would rather see Britain as a genuinely Christian nation, rather than a secular capitalist system holding nothing at its heart.

The only logical conclusion from all this is that Britishness will cast itself as whatever is most politically convenient in the moment: secular or Christian, or some incongruous Dawkins-esque mixture of the two. All that matters is being whatever Islam is not.

In a one-way, almost parasitic relationship, Britishness needs Islam to be its shade, so it can cast itself as the light. And most alarming of all is that the more Islam becomes prominent in the UK, the more this sense of nationalism can feed and grow.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.