Egypt may be looking for a military solution to Ethiopia dam dispute

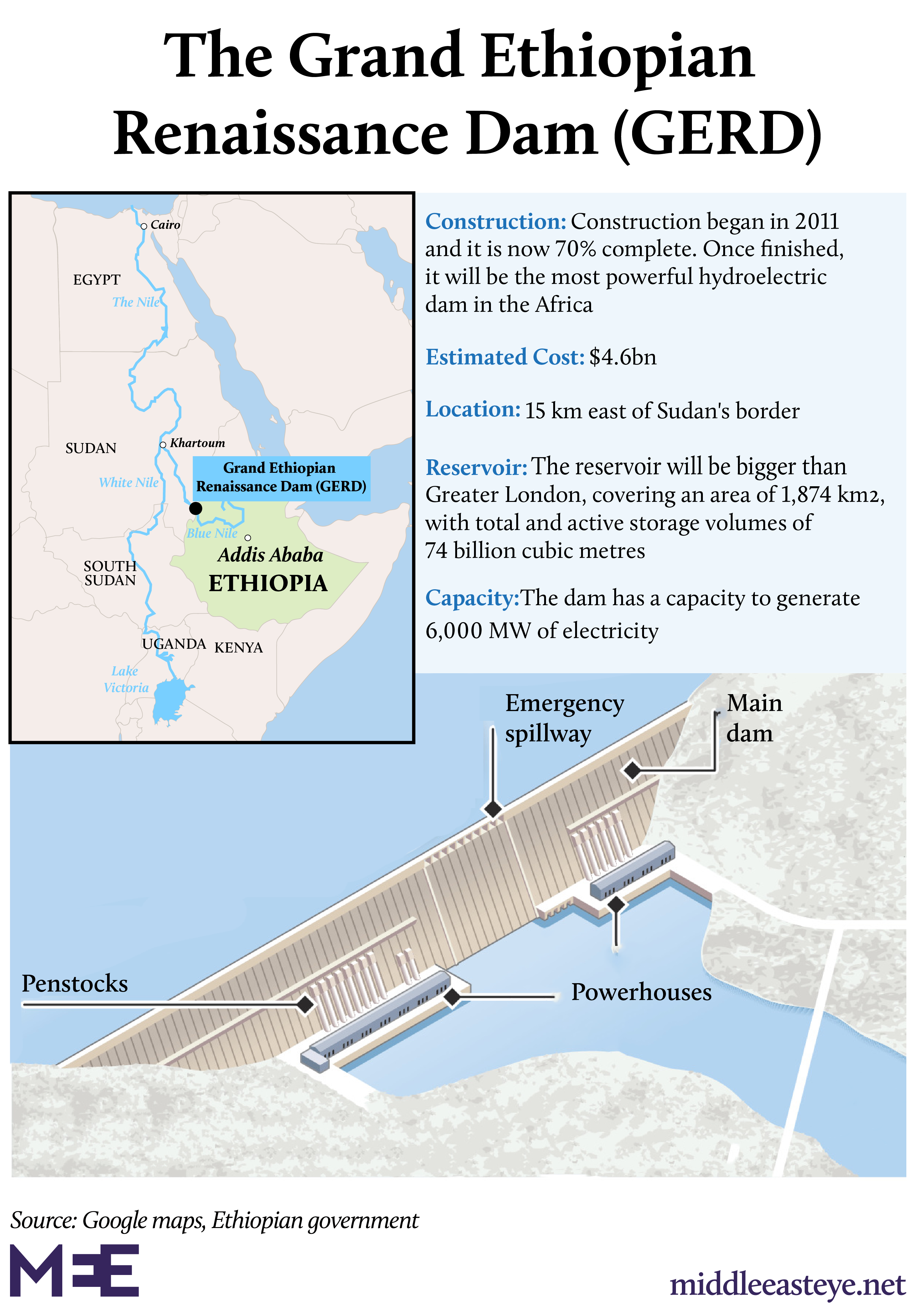

Every state makes decisions on using hard power, such as military force, and soft power, such as diplomacy, in order to protect its own interests, maximise benefits and minimise damage. For Egypt, the main goal of negotiations with Ethiopia over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has been to preserve Egypt’s share of Nile River waters.

But the problem is deeper than the GERD; the real issue lies in the potential building of future dams that may directly affect Egypt. If the dam is built without a legal and binding agreement, other Nile Basin countries may be encouraged to build their own dams in the future.

A decision to go to war would potentially stymie Egypt's attempts to build good relations with other African countries, particularly those in the Nile Basin

For Egypt, wielding the military option against the dam project would be mired by political, security and social challenges. Egypt has been seeking a foothold in Djibouti, Eritrea and Somalia, but it has been unable to establish a military base or to deploy troops in the region. Despite its participation in the Saudi-led Yemen war, Egypt’s role has been limited and ineffective.

The proliferation of other army bases in the region also complicates matters. Djibouti is considered one of the most important sites in the Horn of Africa, through which about 80 percent of Ethiopia’s trade passes, and it is home to US, French, Italian, Chinese, Japanese and Saudi military bases. This limits the effectiveness of the Egyptian navy threatening Ethiopia, which does not have a coastline, and whose border areas in the north and west are characterised by rugged terrain, complicating the prospects for a land-based operation.

The Sinai conflict, which intensified in 2013 and has not stopped to this day, presents an additional challenge for Egypt - making Sudan perhaps a more feasible option for military resistance against the GERD project.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Sudan's transition

Sudan’s internal situation is highly complex, with the country in a transitional phase after the fall of former President Omar al-Bashir. A variety of stakeholders are jockeying for influence, including the military, the Rapid Support Forces, the Freedom and Change (civilian movement), Islamist groups and rebel groups on the periphery, including the Sudan Liberation Army.

The abundance of stakeholders and the lack of cohesion among them makes it difficult to create a unifying vision for the country, with competing ideas on how to manage the transitional phase, alongside different ideological frameworks and tribal/ethnic affiliations. There is an internal power struggle, with each stakeholder aiming to ensure its own longevity, while thwarting other parties.

While relations between Egypt and Sudan are relatively good, they must work to maintain balance among the other actors, particularly since Ethiopia maintains positive relations with Sudan’s civil movement and armed rebels; it could therefore pressure them to adopt positions hostile to Egypt, or to remain neutral.

A military strike on the dam could cause flooding in Sudanese cities and villages near the border with Ethiopia, ultimately putting the Sudanese administration in a position of embarrassment and weakness.

This could discourage it from taking such a risk.

Despite Egypt’s recent progress in strengthening relations with Sudan, including joint military exercises under the name Guardians of the Nile - which carries a clear message to Ethiopia that military force is possible - Cairo has not taken the necessary steps domestically, including obtaining authorisation from the House of Representatives to send military forces abroad. This contrasts with the steps taken by Egypt to flex its military muscle vis-a-vis Libya.

This followed Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s statements on “red lines” in Libya. While he has made similar comments on the GERD dispute, they have not been followed by concrete actions, possibly due to international pressure.

Limited engagement

A decision to go to war would present many complications, potentially stymying Egypt’s attempts to build good relations with other African countries, particularly those in the Nile Basin. With challenges ranging from Ethiopia’s geography, to the political turmoil in Sudan, to the spread of foreign military bases across the region, Egypt would face a tough road ahead if it were to decide on war.

Yet, while an imminent strike on the GERD seems unlikely, the magnitude of the negative repercussions that the dam project could have on Egypt, particularly in terms of water scarcity, may ultimately prompt the regime to take a tougher stance.

A confrontation with Ethiopia, however, would not likely spiral into a full-fledged war; rather, it would be a limited engagement with the aim of entering effective negotiations under international auspices.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.