Egypt: Intifada of the Muslim youth

The political conflict in Egypt certainly has a strong religious component, where different factions have different expectations regarding the role of religion in Egypt. The regime realises this and tries to use Islam to its ends.

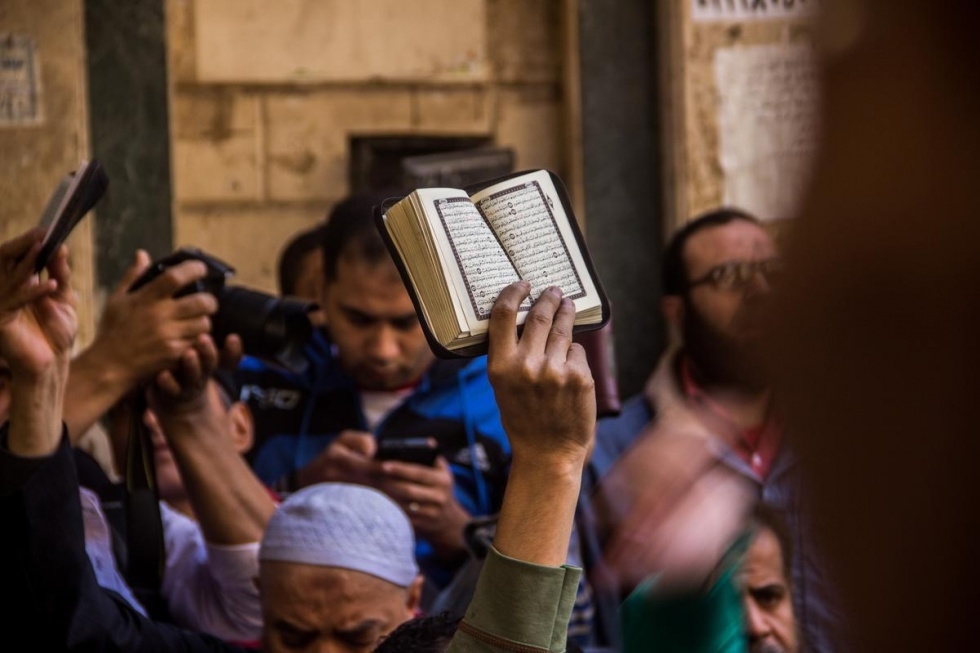

The Salafi Front, which was a member of the National Alliance for Supporting Legitimacy; called for an “Intifada of Muslim Youth” on 28 November. The Front’s youth called upon Egyptians to raise Qurans, call for Sharia, and protest against what they deemed a war on Islamic identity, which is part and parcel of the military rule.

The regime took those calls very seriously. Its sponsored media for days leading to that Friday viciously attacked calls for such protests. The state’s formal Islamic institution, Al-Azhar, participated in the vilifying campaigns. Friday sermons all over Egypt were about the “destructive calls and how to confront them.” Furthermore, Al-Azhar sent 244 envoys all around the nation, warning Egyptians from such calls.

The security apparatus was also in the picture; it heavily cracked down on the Front’s leadership and rounded them up for detention. Those who were not caught, fled their homes. Moreover, Muhammad Ali Bishr, who served as the minister of state for local development under Morsi and the only high profile leader the regime left for possible future negotiations, was also arrested days before the protests. This was a clear signal that the regime is no longer interested in having the possibility of a negotiated settlement.

There was also heavy military mobilisation in preparation of that day and the spokesman for the Ministry of Interior warned that any attacks on public facilities would be met with lethal force.

Some suggested; it would later turn out that the regime in Egypt was also anticipating the outrage that would occur when Mubarak’s charges were to be dropped shortly after. The whole world saw the angry protests in response and ironically 6 April’s Facebook page referred to it as “Intifada of the Egyptian Youth,” perhaps a cheesy thoughtless imitation of the former. Certainly, however the authorities took the calls of 28 November very seriously, and were highly prepared for it, and meticulously devised a plan to diffuse it. But what were these protests that the Muslim Brotherhood endorsed about?

The battle of identity

Egypt’s ruling elite have typically frowned upon “mixing religion with politics.” For decades this has been the case, and those with any visible signs of religiosity have been, for the most part marginalised in media and state institutions.

Today’s current regime is no different, except perhaps it is sending conflicting messages on religiosity. On one hand, it has resisted signs of religiosity in the public sphere and others claimed to support it. For example, a few months back a campaign by the state had started to remove posters or little signs that had “did you pray upon the Prophet today?” Such posters were typically found on taxis, mini-buses and many private Egyptian cars.

Similarly giving platforms to those who promote odd versions of Islam or those who adulterate it is seen by many of the youth who called for the protest on 28 November as an attack on Islam. A prominent professor in Al-Azhar, Saad al-Hilai, has made several controversial remarks on different media appearances. Despite the controversy and uproar which he caused, he kept being invited to talk on television. Similarly “Mido” who always appears in an Azhar gown has spoken of Islam allowing fornication.

Such discussions on what traditionally is undisputable is often seen by Islamist youth as an attack on the “fundamentals of religion.” It does, on the other hand, keep public opinion engaged in such nuances and occupied with topics that do not challenge power politics. However, for Egypt, where religion plays an important role in general life, such statements are certainly odd and for Islamists they are seen as attacks on the essence of their identity as Muslims, that such provocations are deliberate and designed make all aspects of Islam relative and up for debate and thus a religion hollow of meaning.

Moreover, Islam is being marginalised as it is the true sense of Egypt’s identity, and thus source of power and pride, which without masses have no sense of direction and are easy to subjugate and manipulate. This was the case in the post-military coup constitution which bans political parties based on religion and also removed Article 212, which explains what Shariah is. Thus the organisers of 28 November referred to the conflict in Egypt as a “battle of identity”.

Regime and religion

The regime is guilty of what it accuses Islamists of doing; “mixing religion with politics”. It uses religious discourse to its advantage and attempts to use it to justify its repression. For example, a representative of the ministry of endowments gives a religious verdict claiming that it is justified to kill under orders of a ruler - in this case, Sisi, when referring to warnings against 28 November. Nothing new, as the previous Mufti of Al-Azhar (highest authority in the institution to issue verdicts) Ali Gomma, has made similar remarks in front an audience of military and police officers; claiming the Brotherhood and their supporters “stink” and that paradise awaits those who kill them.

The regime certainly does want to appear as supportive of religious conservatism, as a counter weight to Islamists. Whether it’s the recent crackdown on homosexuals or the supposed farcical national strategy, the regime is trying too hard to play “holier than thou”. However, it does not promote any Islamic activism, or propagation of religion that is indicative of Islamic grassroots movements.

In any case, it is not difficult to see through this, and the regime may know that ultimately religion is a losing card to use. In either case, if the regime uses Islam for its legitimacy or tries to curb it altogether, it is not going to eliminate Islam as a mobilising factor against it.

-Mustafa Salama is a political analyst, consultant and freelance writer. Salama has extensive experience and an academic background in Middle East Affairs.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Cairo, Egypt - 28 November: A protester holds a copy of the Quran aloft as during an anti-regime rally following the Friday Prayer in El-Matareya neighborhood of Cairo, Egypt on November 28, 2014

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.