Egypt protests: Sisi's iron fist is no longer enough

On 2 September, former military contractor Mohamed Ali began releasing a series of videos alleging corruption by Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, his family, top army generals and close confidants. Since then, the Egyptian president has been rocked by new challenges to his rule.

Ali’s videos and the protests they have sparked have taught us several important lessons about the Egyptian political landscape. I’ll address a few of the lessons here.

A dwindling popularity

Sisi is not nearly as popular as his officials and obsequious media apparatus like to project.

Since taking power in a military coup in July 2013, the Egyptian power structure, which includes a powerful news and entertainment media system, has suggested that the entire Egyptian nation is behind Sisi. Only a small handful of "terrorists" and "traitors", as the narrative goes, are disloyal to the regime.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

If Sisi were confident in his popularity, he wouldn’t see the need to completely stifle anti-regime protests.

When anti-Sisi protests erupted last weekend, Egyptian media pundits took to the airwaves to proclaim that only "30 or 40" Egyptians protested. Predictably, protests were blamed on the now-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

Realities on the ground, however, paint a different picture. Sisi is disliked by large swaths of Egyptians, and he knows it.

If Sisi wasn’t concerned about his dwindling popularity, he wouldn’t have needed to prevent scientific opinion polling, or scold foreign media outlets over their coverage of Egypt. More importantly, if Sisi were confident in his popularity, he wouldn’t see the need to completely stifle anti-regime protests.

In theory, a few small anti-Sisi protests could help the regime project an air of democracy and freedom. But, over the past week, the regime has taken extreme measures to intimidate opposition.

Lethal force

After arresting hundreds of protesters last week, the regime reiterated that protests are illegal, said they would be dealt with “decisively”, threatened the use of lethal force, continued a media blackout, interfered with social media sites, cancelled subway stops near Cairo’s city centre, cancelled all football league matches for the weekend, and used tanks and riot police to completely shut down all main roads and bridges leading to major squares.

Why are Egyptians protesting against Sisi?

+ Show - HideOn Friday 20 September, crowds demonstrated in Cairo and other cities in the first major street protests against president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi since he crushed peaceful protests after coming to power in a military coup in 2013.

The protests came after calls from Mohamed Ali, an Egyptian businessman-turned-whistleblower, for Egyptians to take to the streets following a football match that evening between Al Ahly and Zamalek, the country's biggest clubs.

The owner of a real-estate company that has worked with the Egyptian armed forces for 15 years, Ali has been leading an online anti-Sisi campaign since the beginning of September through a series of video testimonies accusing the president of corruption and misappropriation of public funds.

Some of the projects assigned to his company, he has said, are palatial residences worth millions of dollars built for Sisi and his family since he became defence minister in 2012.

In his only public response to the claims, Sisi did not deny building new palaces, and vowed to build "more and more" palaces "in the name of Egypt".

Sisi's remarks have ignited more opposition, with social media campaigns and hashtags calling on Sisi to step down going viral in Egypt and worldwide.

At a time when opposition is criminalised and tens of thousands of political prisoners languish in Egyptian jails, Ali's revelations have sparked a rare public debate on the military’s opaque budget and the contrast between Sisi’s calls for Egyptians to tighten their belts amid stringent austerity measures and the billions spent on luxury palaces.

Ali, now based in Spain, claims that he is acting individually at his own risk.

But many observers have raised questions over whether he has supporters within Sisi's government who are standing behind his calls for protests or even plotting a coup.

Opponents of Sisi from across the political spectrum have expressed sympathy for Ali’s online campaign, while TV channels run by exiled opposition leaders have reposted his daily videos, watched by millions.

A Friday Google Maps image of the area near Tahrir Square showed the extent to which the regime had gone to eliminate the possibility of a protest spectacle.

Sisi has never been as popular as his fawning media have told us. In 2013 and 2014, shortly after the coup (and at the height of his popularity), a pair of western scientific opinion polls showed that Sisi’s approval rating was about on par with Mohamed Morsi, the freely elected president ousted in the coup.

The Sisi regime’s recent actions seem to suggest they are aware of the president’s dwindling public support.

Two Egypts

There are two Egypts.

Egyptians who oppose Sisi are projected by the regime and its media outlets as traitorous un-Egyptians and “terrorists”, while Sisi supporters are depicted as true Egyptians.

Upon Sisi's arrival at Cairo International Airport on Friday, a journalist greeted him with a question about the planned anti-regime protests. Tellingly, her question referred to the protesters as “terrorists”.

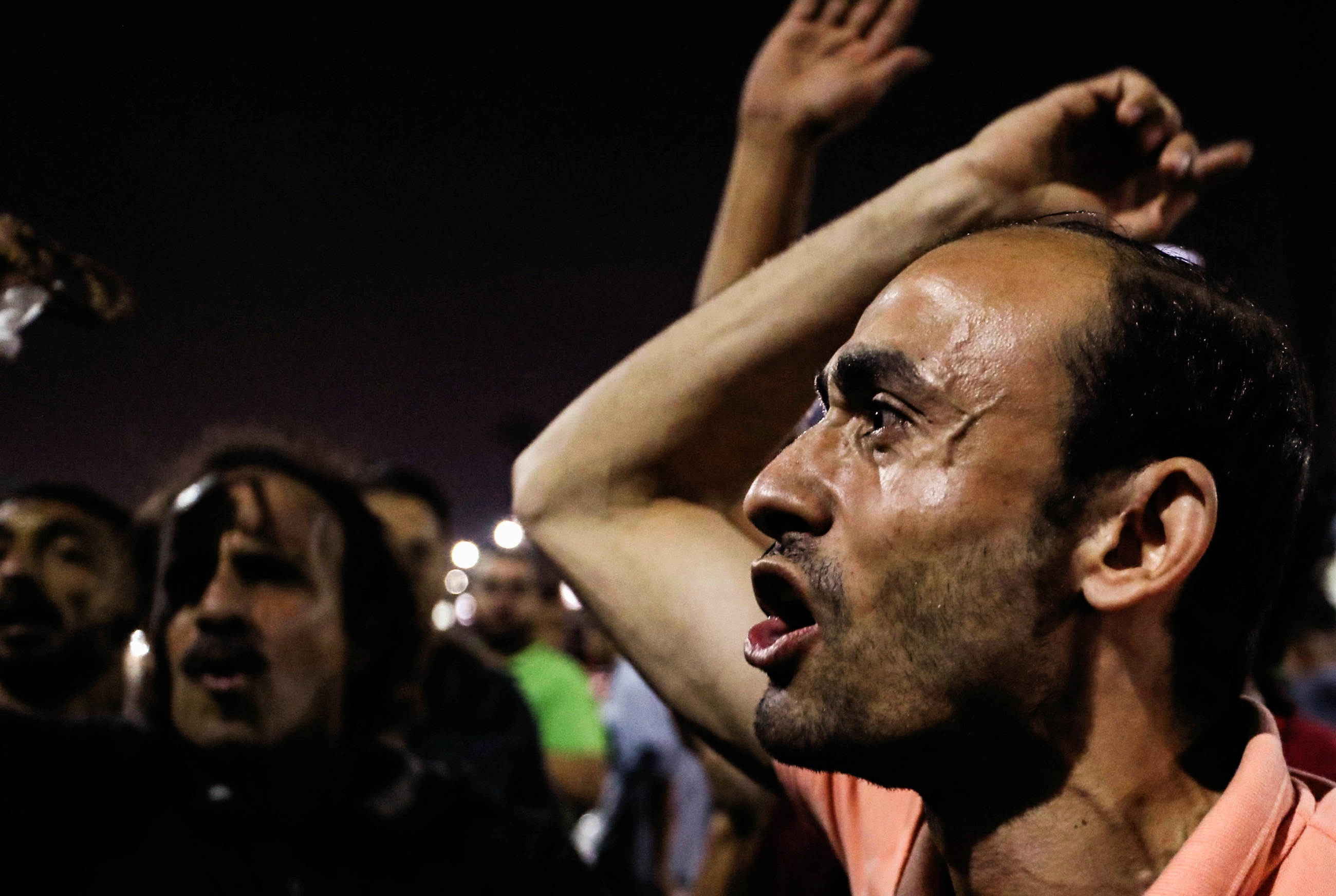

Anti-Sisi Egyptians are reminded - in word and deed - that they are disloyal, criminal, and not allowed to protest. More than 2,000 Egyptians have been arrested for participating in the 20 September protests. More Egyptians were arrested on Friday, as the regime used brute force to shut down some demonstrations.

On the other hand, Egyptians who support Sisi were encouraged by the regime to demonstrate publicly in violation of its own anti-protest law which stipulates that protesters should seek a prior permission from the interior ministry to be able to organise a protest.

The regime used businesspeople and celebrities to encourage a good turnout, and provided music and entertainment. The government also provided bus transportation to the pro-Sisi demonstration, gave out food to hungry demonstrators, and issued bribes as incentive to attend.

Powerful but not invincible

Sisi might be powerful, but he is not invincible.

After taking power, the Sisi regime massacred hundreds of unarmed protesters in the streets, formally banned all serious opposition parties and groups, shut down all opposition media, arrested tens of thousands of political leaders and activists, effectively eliminated NGOs, and introduced draconian legislation prohibiting protest and other public displays of dissent.

Since at least 2014, Sisi has been an authoritarian in the truest sense. His show of power over the past week underscores his absolute control over all of Egypt’s state institutions, and also the extent to which fear of arrest and death keeps many Egyptians at home.

But the demonstrations of the past week also reveal a chink the regime’s proverbial armor. The protests show that many Egyptians, in many governorates, are not afraid to risk their lives.

Ali is unlikely to stop producing videos, and he claims he has a good deal more evidence of government corruption. As the economy continues to spiral out of control, leaving the majority of Egyptians poor and bereft, and as Ali and others continue to call for a “revolution of the people”, Sisi is likely to face more dissent.

A new culture

If events of the past few weeks are any indication, Sisi has a new culture of protest and unrest to deal with. How long can the regime keep tanks in the streets, and how many people is it willing to arrest and kill?

At what point might Egypt’s military, which controls upwards of 60 percent of the Egyptian economy, decide that Sisi is no longer worth the trouble? These are questions that cannot be answered right now, but which may well be answered in the coming days, weeks and months.

For Sisi, 2019 looks very different from 2013, when he was supported by powerful governments in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, and also tacitly supported by a stable American administration.

At present, governments in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and Washington are mired in their own problems, unable to offer Sisi meaningful support.

Stay tuned. Egypt’s revolution is far from finished.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.