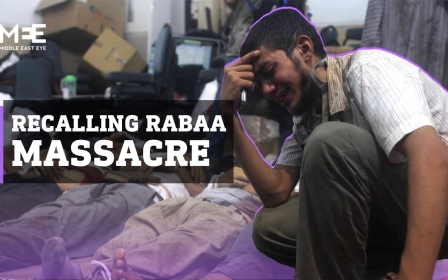

Egypt: How the Rabaa massacre cemented political polarisation

The Rabaa massacre [in August 2013] represented a pivotal event for the contending players and a turning point for Egypt’s post-coup politics.

After Rabaa, the anti-[Mohamed Morsi] camp needed to rationalize the violence deployed against the protesters. It thereby unwittingly paved the way for an authoritarian restoration. At the same time, the victimized protesters were unable to abandon their unsuccessful claims to legitimacy. This precluded broader popular solidarity with those killed in Rabaa Square. [Human Rights Watch said "at least 817 and likely more than 1,000" protesters were killed in the square on 14 August 2013.]

The massacre also set the conditions for future protests: as the Anti-Coup Alliance defined itself in antithesis to coup forces, it responded not by adopting violent resistance, but by diversifying its contentious repertoire.

[…]

After the massacre

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Prior research on violent repression events and massacres showed how their emotional impact can translate into symbolic moments that give meaning to social struggles.

For instance, Della Porta demonstrated through life cycle interviews how the fascist massacre in Piazza Fontana in Milan in 1969 left a lasting mark on the collective memory of Italian leftists, sparked interest in and solidarity with ongoing militant mobilization activities, and moved to the center of leftist discourses: The mobilization after the massacre and the death of an anarchist, Pinelli, while being interrogated by police during the investigation represented very intense experiences for many activists. In death, comrades became heroes.

Several research participants described their time at the sit-ins as a unique personal experience that changed their understanding of solidarity

Extreme emotions were aroused by the memory of the “April days of 1975.” In a similar vein, Rabaa and its victims moved to the center of the Anti-Coup resistance discourse. Sharply contrasting their prior experiences of everyday life in the sit-ins, the massacres became a “collective biographical landmark” for the protesters. For many of those protesting on Rabaa and Nahda Square, the weeks of occupation had not only been a strategic tool but had also enabled the organization of alternative and ideal-typical miniature societies.

Particularly the Rabaa sit-in with its sophisticated internal logistics, functional differentiation, work-sharing, community activities, and social support structures had a strong prefigurative character. Several research participants described their time at the sit-ins as a unique personal experience that changed their understanding of solidarity and meaningful life.

Their glorifying descriptions effectively echoed previous accounts by protesters of their experiences during the 18 days on Tahrir Square in 2011. Certainly, the Anti-Coup camps neither harbored an equally pluralist cross-ideological coalition as Tahrir had during the Arab Spring nor did they give voice to the aspirations of as many different segments of Egyptian society.

But Ahmad Shokr’s (2015) descriptions of the square’s identity establishing communitarian dynamics, if complemented by a strong religious component, to a large part captures what the tent cities represented for the Anti-Coup supporters. They were experienced by their participants as utopic spaces, where an idealized vision of society could be construed and lived that drew on Islamist discourses as much as the cultural stock of the 2011 camps. Over 47 days of occupation, particularly Rabat “turned into a veritable polis, where people were bound together by more than a common political demand”.

Midan Rabaa al-Adawiya and Al-Nahda housed a society under construction where people with different socio-economic, ideological, and demographic backgrounds met in collective resistance against the installation of a new historical block in the shape of the military-backed coup forces.

Against conventional wisdom, the sit-ins were not only populated by rank and file Muslim Brothers and their families. According to several interlocutors, like Tahrir, Rabaa represented an egalitarian utopia that cut across classes, age groups, and organizational boundaries. Albeit shunned by liberal and secular players – some of whom were, in principle, sympathetic to the rights of the [Morsi] supporters to freely voice their opinion but did not join the sit-ins, because they disagreed with the protesters’ goals – the tent cities were populated by Egyptians from all walks of life; secular and devout, liberal and leftist, revolutionary and reactionary.

[…]

Utopian social order

A study of the socio-economic profiles of those who were killed in the Rabaa dispersal shows that the protest participants came from more than half of the country’s districts, including the more prosperous and urbanized parts of the country (Ketchley & Biggs, 2015). In a sense, the camp was not so much pro-Brotherhood as it was anti-coup. Conversations with participants of the Anti-Coup campaign pointed to the presence of, at least, two factions of players on Rabaa and Al-Nahda Square.

The first encompassed actual supporters of deposed President [Morsi]. By contrast, the second comprised citizens who were not necessarily pro-[Morsi] but, above all, opposed to the way he had been removed from office.

Among the latter, some shared the conviction that the former president should have stepped down or that he should, at least, have been removed from office through impeachment as described in the constitution.

This bifurcation of motivations for being anti-coup represents a major difference to the June 30 protest coalition, whose major factions welcomed military intervention as a way to not only depose the president but also repeal a disliked constitution. It certainly was in the the National Alliance in Support of Legitimacy (NASL)’s interest to portray the Rabaa sit-in as a horizontally organized and diverse community, as this narrative blurred the de facto existent hierarchies between Ikhwan [Muslim Brothers] and non-Ikhwan among the camp’s members.

In truth, Brotherhood members and Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) functionaries played a leading role in most committees on the square and were crucially involved in the logistical efforts necessary for the smooth functioning of this utopian social order, including the provision of basic necessities and the organization of security.

However, among the NASL grassroots, the Brotherhood activists only made up between a quarter to a third, as several interviewees stressed who attended the sit-ins.

Eyewitnesses who toured the campsite in the days before their dissolution came to a similar conclusion. Accordingly, most participants of the sit-in were not formal members of either organization. For weeks, Midan Rabaa and Al-Nahda became “social laboratories” where the variegated forces allied in the NASL negotiated, tested, and shaped their new ideal political community.

From the political debates on the Rabaa-podium to the mundane acts, such as cleaning the streets, re-painting the surrounding walls, distributing food, or organizing the night shifts, the everyday practices of collectively sustaining an alternative order, which rivaled that of the post-coup state, provided moments of inspiration for the formation of a strong collective identity that overran the political distinctions between the movements aligned in the NASL.

'Supernatural qualities'

On August 14, 2013, this “effervescent community” was abruptly shattered. The Anti-Coup movement’s coherence, however, endured. The collective experience of brutal state violence endowed further sense and identity to the protesters’ subsequent struggle: Framed by the coalition as a “crime against humanity in the holy month of Ramadan” (NASL, 2013), the massacres became the central theme for the campaign, dominating the imagery and collective action frames in the second half of the examined timeframe.

As Dawn Perlmutter noted, the critical juncture of Rabaa and all of its corresponding actors, figures, imagery, and symbols were virtually “endowed with supernatural qualities.”

The dispersals also caused a moral shock that transcended the geographical boundaries of the raided squares. Similar to Guantanamo or Abu Ghraib becoming symbols for the ubiquitous violations of human rights in the name of the global war on terror, Rabaa became a symbol for authorities’ disdain for civil opposition, civic rights, and the peaceful solution of political conflict.

The Rabaa and Al-Nahda massacres marked not only a turning point for the Anti-Coup protesters, but also for their antagonist other

The massacres resonated strongly with universalized norms of human dignity and civil rights. Therefore, they quickly turned into a transnational symbol for state abuse of repressive powers.

Ultimately, the contentious episodes in the summer of 2013 caused a two-sided backlash.

The Rabaa and Al-Nahda massacres marked not only a turning point for the Anti-Coup protesters, but also for their antagonist other. Neither the protesters nor the authorities could take a step back afterward and offer concessions to their opponent.

To legitimize its violent crackdown, the regime resorted to vicious nationalist propaganda that rivaled the NASL’s legitimacy discourse, branded the Brotherhood and its allies as terrorists, and securitized Egypt’s protest arena as an illegitimate sphere of insurgent politics.

The Rabaa massacre made this antagonizing narrative irreversible, thus cementing political polarization and paving the way for the restoration of authoritarian rule.

The above has been excerpted from Jannis Julien Grimm’s Contested Legitimacies: Repression and Revolt in Post-Revolutionary Egypt (Amsterdam University Press, 2022)

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.