Rabaa massacre: Nine years on, Egyptians still live in its shadow

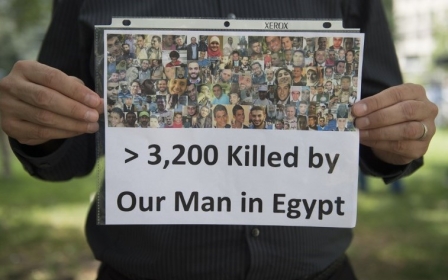

This week marks nine years since the August 2013 Rabaa massacre, an unprecedented episode of state-led violence against civilian protesters as part of the counter-revolutionary strategy led by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, now Egypt's president.

Rabaa did not happen in a vacuum. It was the culmination of the deep state's counterrevolutionary efforts

Commonly referred to as the end of the Arab Spring, the massacre unfolded as police and military forces charged at protesters in Rabaa al-Adawiya and al-Nahda squares in Cairo, attacking them with armoured military vehicles, live ammunition and snipers.

Military forces then set the protest sites on fire, destroying the Rabaa mosque in the process. It is estimated that more than 800 people were slaughtered, with many ending up in makeshift mass morgues; some families never had the bodies returned for proper burial, and dozens simply disappeared.

In 2018, after an internationally condemned mass trial, 75 people were sentenced to death and more than 600 were given hefty prison sentences.

Many describe Rabaa as the worst mass killing of demonstrators in modern history, and today, nine years later, Egyptians still live in the shadow of those horrific events, which cemented the installing of a counter-revolutionary regime characterised by a steady decline in human rights, heavy patrolling of political space, and the erasure of what little sociopolitical gains had been made after the 2011 uprising.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Rabaa did not happen in a vacuum. It was the culmination of the deep state's counter-revolutionary efforts, which had been at play since the removal of longstanding dictator Hosni Mubarak amid protests in early 2011.

The toppling of the Mubarak regime opened up Egypt's political space after decades of oppression, allowing the emergence of previously outlawed political opposition groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Ultimately, it set Egypt on a path, albeit short-lived, towards democratic transition.

History of repression

The Brotherhood was one of the main political actors to take centre stage after Mubarak was toppled. Founded in 1928 by schoolteacher Hassan al-Banna, and using the slogan "Islam is the solution," the group preached a gradual Islamisation of the state, alongside a strong anti-colonial narrative that soon built a strong popular base.

The Brotherhood was outlawed in 1948 and has since had a troubled relationship with subsequent regimes, one marked by brief periods of cooperation but overwhelmingly by persecution. Despite this repression, the Brotherhood evolved over the decades into one of Egypt's most organised opposition political movements and a key civil society actor.

It is thus not surprising that despite its leadership's initial reluctance, Brotherhood members and affiliates were instrumental to the success of the 2011 uprising. The movement heavily capitalised on the opening up of the political space after Mubarak's overthrow.

In April 2011, the Brotherhood founded its own political party, the Freedom and Justice Party, and the following year party leader Mohamed Morsi became the first freely elected civilian president in Egypt's modern history.

While this victory was a major milestone for the Brotherhood, it was not welcomed by Egyptians as a whole. Many refused to support the Brotherhood, while others did so reluctantly, aiming to avoid the election of a representative of the deep state - referring to themselves as "lemon squeezers," in a nod to the custom of squeezing lemon juice onto food on the verge of spoiling.

Any means necessary

Beyond the lack of overwhelming public support, the Brotherhood also struggled with its sudden move from the periphery to the centre of Egyptian politics. While the movement learned how to survive and even thrive under repression, it lacked the experience necessary to govern a country undergoing a democratic transition.

Internal divisions, the legacy of decades of isolationism, and the group's refusal to cooperate with other political forces soon led to discontent and protests against Morsi's government. In the end, the Brotherhood's rule was remarkably short-lived; exactly one year after the presidential election, nationwide protests broke out again, this time blaming Morsi for the steadily deteriorating economic and political situation.

This was the opportunity that the military deep state had been waiting for. On 3 July 2013, protests were backed by the army, and Morsi was deposed in a military coup led by Sisi, who would become president the following year. This was the ultimate proof that a new political order had not emerged in the aftermath of the 2011 uprising. The coup marked the beginning of a counter-revolutionary drive that eventually led to the Rabaa massacre.

After Morsi's removal, Muslim Brotherhood members, supporters and pro-democracy civilians occupied Rabaa and Nahda squares, with more than 85,000 protesters demanding Morsi's reinstatement and a return to democratic rule. The sit-ins lasted for about six weeks, until the massacre that still haunts Egyptian society today.

The Rabaa massacre sent an overwhelming message. This heinous act was fundamental to the stability of the counter-revolutionary regime, showing that it would go to any means necessary to seize back power, erase what feeble hopes for change had emerged after 2011, and broadcast that any form of political opposition would not be tolerated.

Business as usual

The fallout from Rabaa was not as drastic as one might have expected. Despite the brutality, many Egyptians supported the dispersal of the sit-ins, which liberal politicians feared would be a breeding ground for Islamist extremism. Those who did not support Morsi lamented the disruptions the camps caused in already-congested Cairo. While both the EU and US condemned the killings, they carried on business as usual with the Sisi regime, and, to this day, no one has been held accountable for the massacre.

Still, it is undeniable that Rabaa dramatically changed the sociopolitical landscape in Egypt. Human Rights Watch concluded that the massacre was a premeditated assault equal to, or worse than, China's Tiananmen Square assault in 1989.

Civilian and liberal opposition groups in Egypt are struggling to find space under an increasingly oppressive regime

The impunity for its perpetrators also gave Sisi a green light to crack down on political dissent, leading to the worst human rights crisis in Egypt's modern history. As the state has amassed exceptional powers, laws have been passed to curtail freedom of expression, protests and political association, while the regime has heavily censored opposition media outlets.

An estimated 60,000 Egyptians have been arrested for political reasons since Rabaa. Many have been held indefinitely without trial. The Rabaa massacre not only reinstated the deep state, but it erased any hopes for change post-2011.

The Muslim Brotherhood has been living in forced exile while the movement attempts to regroup and find a new direction. While repression and illegality are nothing new for the Brotherhood, one of its biggest challenges now is the need to rebuild a popular base at home and to convince Egyptians that it can be a moderate and inclusive political force.

Meanwhile, civilian and liberal opposition groups in Egypt are struggling to find space under an increasingly oppressive regime, hoping to revive the transitional process that was so brutally halted by the blood spilled in Rabaa.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.