Egypt: The road from the July 1952 revolution to today's feeble regime

On its 65th anniversary, the Egyptian Free Officers’ movement and the regime that was born from its womb continues to stir interest, debate and division.

What did the Free Officers’ regime do to modern Egypt? Did the July republic rescue Egypt from an inevitable ruin it was heading to? Or did it drive it into decline? Can Egypt’s current conditions in essence be interpreted in terms of what the group of young officers did at dawn on that day in July 1952?

For a brief period of time, it seemed as if the Egyptians, as a people and not as a ruling class, implemented their collective will and took charge of their future

Egyptians never exhibited a loss of trust in their state and ruling class as they did during the first decade of this century, not even in the wake of the painful defeat of June 1967. The January 2011 revolution was not only a decisive popular referendum on the country’s situation, but was also the Egyptians' great endeavour to rescue the country from an imminent destiny.

For a brief period of time, it seemed as if the Egyptians, as a people and not as a ruling class, implemented their collective will and took charge of their future. Yet, the defeat inflicted upon the revolution and on the process of democratic transition triggered by it returned Egypt once more to the grip of army officers. It is perhaps this vicious cycle that bestowed a different meaning to the 65th anniversary of the July 1952 movement.

Sources of social power

Michael Mann, professor of political sociology at UCLA, published his major work in the 1990s The Sources of Social Power in four volumes. Mann’s work generated wide interest, and a lot of criticism was directed at him. At times, his work was compared with the scale and impact of Max Weber’s intellectual project at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Early in 2012, Mann republished the four volumes of his book with long introductions in which he responded to some of the criticisms levelled at him. He acknowledged some of the errors and explained some of the vagueness that crept into his analytical approach that almost covers the history of power and its social manifestations from ancient times to the end of the Cold War.

Where I found no disagreement between Mann and his critics was the basic theory underpinning the book in its four volumes. Mann says that the sources of social power belong to four circles: the economic, the political, the military and the ideological circles.

Yet, these sources do not function in parallel. Instead they are in constant interplay; each leaves an impact that is inseparable from the other circles. Such interaction results in outcomes and transformations that are difficult to predict or anticipate in absolute or decisive terms.

Unexpected victory

To what extent can Mann’s basic theory be applied to the July republic and its transformations during the six decades that preceded the eruption of the January 2011 revolution?

Most probably, the Free Officers did not intend for their move to become a total revolution and a blatant seizure of power. Yet, as soon as the coup succeeded, the officers realised, despite limited obstacles, that the Egyptian state succumbed to them and that there was no rival power to challenge them.

With unexpected ease, the royal family swiftly left the country into exile. The previous ruling class was removed from power without any significant opposition. Afterwards, the Muslim Brotherhood, the bigger partner and then opposition, was toppled and silence was imposed on the small liberal groups with the use of various levels of repression.

However, the republic was founded on a pragmatic rather than an ideological vision. The ideological – Arab nationalist and (limited) socialist - inclination only developed later. The economic reforms, whether in land reform or accelerating the wheel of industrialisation (that began in the 1920s), did not lead to a tangible change in the Egyptian class structure.

In other words, the republic relied on two main sources of power: the army and the state bureaucracy. Whoever led the republic controlled its institutions, enacted its policies and programmes. This was a military-civil bureaucracy. Building a democratic system was not one of its concerns.

The army and the state

The truth is that the relationship between the two wings of the ruling bureaucracy, the military and the civil, was not always smooth or stable. Even throughout the first one and half decade after July 1952, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the regime’s charismatic leader and president of the republic, tried to put the military back in its barracks and sever the umbilical cord that linked the army on the one hand and the administration of the state and political life on the other.

But not until the defeat of June 1967 would he achieve tangible success in putting an end to the direct role of the army in politics. Yet, such success was temporary.

When Anwar Sadat assumed power, nothing was left of the power of the nationalist ideology except a distant memory

Regardless, the biggest impact of the 1967 defeat was imposing restrictions on the ideological root of the forces upon which the republic depended, namely the Arab nationalist idea, and Egypt’s leadership of the Arab nationalist movement, which it acquired rapidly since the end of the 1950s and early 1960s.

When Anwar Sadat assumed power, nothing was left of the power of the nationalist ideology except a distant memory that was quickly sliding into oblivion.

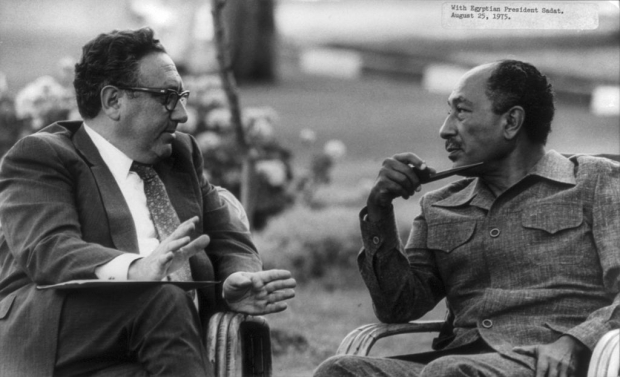

Sadat laid down new foundations, especially in the wake of the October 1973 war, for the relationship between the military bureaucracy and the regime, guaranteeing the army a share in the regime while bolstering the civilian image of the republic and banning the army from playing a direct or blatant role in governance or in political life.

However, the seat of of the presidency in the republic, the most powerful position in the regime, remained exclusively the prerogative of the upper class of army officers. In a growing global climate that saw the ascendance of the neoliberal idea, Sadat tried to create a new source of economic power for the regime by adopting what he called the policy of economic openness. The idea was to pump new blood into the Egyptian upper classes and expand the middle class.

Sadat’s economic strides were slow and cautious, to some extent. Yet the policy he adopted did not culminate and reach its zenith until much later during the reign of his successor, President Hosni Mubarak.

The class of rich property owners and the families of the upper middle class from the royal era regained their position at the top of the Egyptian economic pyramid together with an increasing number of the sons and daughters of the republican civil and military bureaucracy.

It was in this way that Egypt truly became an integral part of the global market and witnessed, albeit for a brief period, an influx of foreign investment capital, Arab, European and American.

Wealth and poverty

Yet the results were disastrous. Instead of creating gradual affluence, the new economic policy augmented the massive disparity in living standards and in life as a whole, between a tiny percentage of the populace who were extremely rich, and millions of poor people or those who were well below the poverty line.

But since neither Sadat nor Mubarak were serious about democratising the regime, the military–civil bureaucracy continued to control the state establishment, which sought, whether by opening the markets or by adopting methods of generous appeasement, to secure its share in the available limited wealth.

Toward the end of the Mubarak era, on the eve of the eruption of the January 2011 revolution, the republic’s sources of power had already been restored to what they used to be in the 1950s.

Having completely shed its ideological power, the republic lost the promise of economic prosperity and failed to take a single step in the direction of building democratic legitimacy.

However, the difference between the people of the 1950s and the people of the 2010s - the social structure of both peoples, their relations with the world around them and their ambitions – was huge, and this is what led to the eruption of the popular revolution.

The 2013 coup aborted the potential for reforming the republic and gave rise to a narrower and uglier regime than the one Mubarak’s republic ended with. This is what renders the new regime weaker and more brittle.

On its 65th anniversary, the July 1952 regime and the Egyptian republic seem to be in their worst condition ever.

- Basheer Nafi is a senior research fellow at the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A waving and shouting crowd demonstrates against Great Britain in Cairo on 23 October 1951 as tension continued to mount in the dispute between Egypt and Britain over control of the Suez Canal and Sudan. (Wikicommons)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.