Is Egypt on the brink of another uprising?

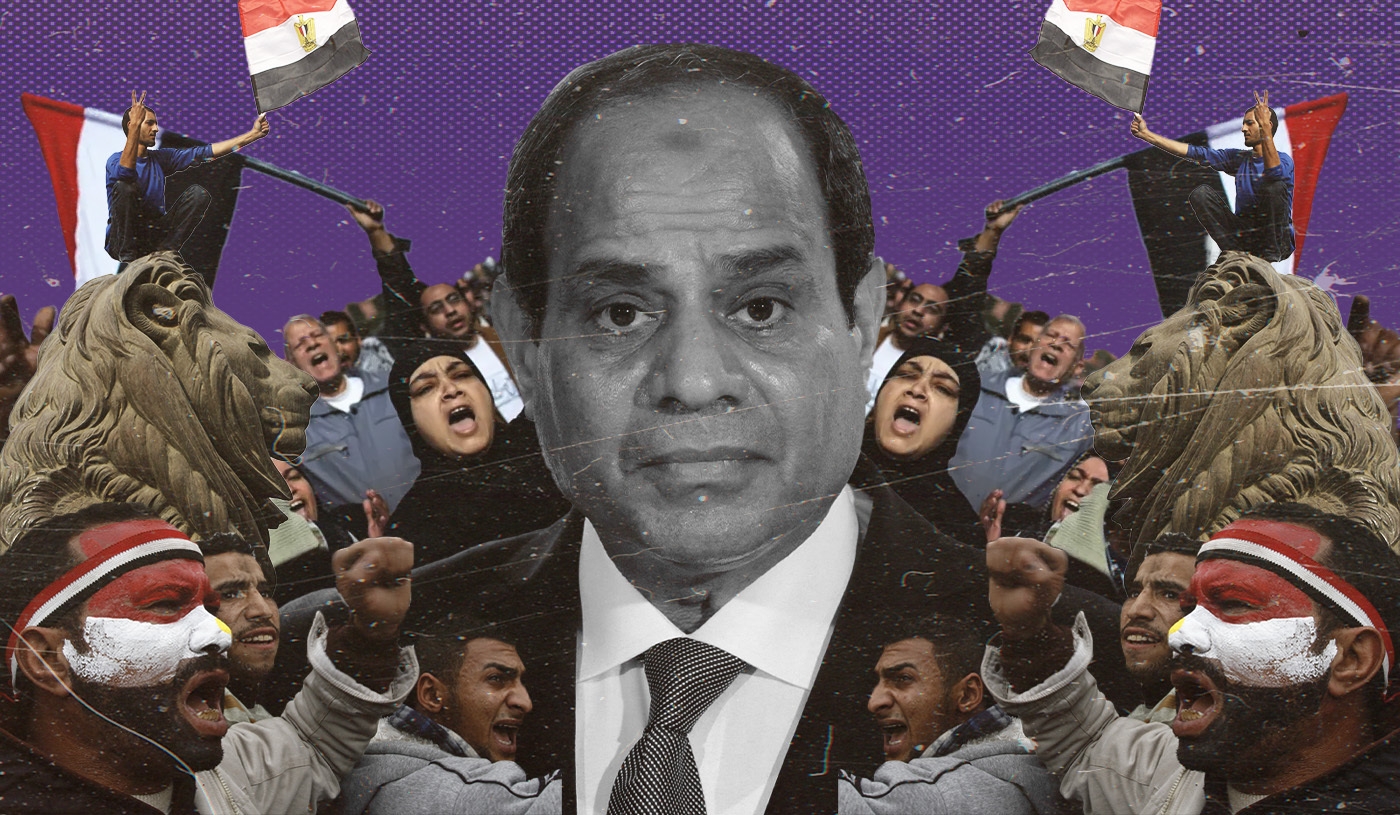

The 25 January marks the 12-year anniversary of the Egyptian contribution to the Arab Spring, an 18-day national uprising that led to the ousting of 30-year dictator Hosni Mubarak.

Following Mubarak’s 11 February 2011 forced resignation, Egypt held a series of free-and-fair elections and referenda, and voted in its first-ever civilian president, Mohamed Morsi.

Egypt currently stands in the midst of an unprecedented economic crisis - one that could ultimately lead to Sisi's doom

But Egypt’s "deep state", led by the national armed forces, was never content to let Morsi, or any other civilian, hold true power. The military colluded with Mubarak regime holdovers, anti-democratic liberals, media outlets and police to orchestrate a July 2013 coup d’etat against Morsi.

Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who served as Morsi’s defence minister for one year, led both the coup and the national transition to unbridled authoritarianism.

Sisi was elected president in a 2014 sham election, then presided over unprecedented human rights abuses, completed the elimination of Egyptian political opposition, and laid the legal groundwork for autocratic rule.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

During his presidential campaign, and again during the early days of his rule, Sisi promised Egyptians economic prosperity. By all accounts, he has failed to deliver. Egypt currently stands in the midst of an unprecedented economic crisis - one that could ultimately lead to Sisi’s doom.

Economic mismanagement

The coup was financed largely by Gulf dictatorships afraid of a democratic turn in the Arab region. In 2013 and 2014, Sisi received tens of billions of dollars in grants from Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In addition to these grants, the Egyptian regime received large loans from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, China, the Arab Monetary Fund and the African Development Bank.

Yet, rather than spending cash influxes on education, healthcare, affordable housing or revenue-generating projects, the regime chose instead to spend billions on vanity projects that fed Egypt’s military’s economy: roadways, a monorail, presidential palaces and luxury hotels. Last year, Sisi also purchased a new presidential jumbo jet for $500m.

In 2016, construction began on a $50bn administrative capital city. The new capital, which includes the tallest skyscraper in Africa and a mega-mosque, has lined the pockets of military-owned companies and is being designed primarily to serve wealthy Egyptian elites.

Importantly, the new capital’s military and security complexes, as well as its distant location - it is situated about 45 kilometres from Cairo - are thought to offer it protection from a potential future uprising.

The 2020 coronavirus pandemic and 2022 Russia-Ukraine war have exacerbated Egypt’s already dire economic circumstances. This month, about a year after Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine and nearly three years after the start of the pandemic, the Egyptian pound weakened further, devaluing to about 29 pounds against the dollar. Further devaluations are expected in the coming months.

The weakening of the pound has led to staggering increases in import prices, a reality that has contributed to skyrocketing inflation. Last month, inflation rose to nearly 22 percent. Average Egyptians, who have also suffered through drastic subsidy cuts, have been left unable to make ends meet.

A 'beggar state'

Loans, in particular, have had a deleterious effect on the Egyptian economy, creating what experts consider a debt crisis and leading to even greater military control over the economy. A CNN report recently argued that Egypt has become “addicted to debt”, while professor Robert Springborg posited that Sisi has transformed the country into a “beggar state”.

As a result of excessive borrowing, a considerable portion of Egyptian government spending is now devoted purely to paying off debt. Loans have mostly been mismanaged by the Egyptian state.

Stephan Roll, head of the Africa and Middle East research division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, said that loans have primarily been used "to protect the assets of the armed forces, to finance major projects in which the military could earn significant money, and to pursue an expansive military build-up".

Under Sisi, Egypt’s foreign debt has tripled to nearly $160bn.

In many ways, Sisi’s continued survival has depended on support from Saudi Arabia and the UAE - and he knows this. At recent events, Sisi has gone out of his way to thank Saudi Arabia and the UAE for their continued economic support, even going so far as to suggest that Egypt “would not have continued [to exist]” without their aid.

But free Gulf money appears to be drying up, or at least coming into short supply - a reality that Sisi’s public addresses have made clear. In summer 2022, he used a news conference as an opportunity to ask his “brothers in the Gulf” for additional aid. He repeated the plea at other events.

Later in 2022, Sisi’s tune changed to one of desperation, as he seemed to acknowledge that further Gulf aid was unlikely to come, or at least unlikely to be as substantial as he hoped. In a November speech, he said: “Even our brothers and friends [in the Gulf] have developed a firm conviction that the Egyptian state will be unable to again stand on its own two feet. They also believe that the support they’ve provided [to Egypt] over a period of many years has created a culture of dependency.”

Sisi’s words were telling, and seemed to suggest that his allies in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have grown tired of sending money to Egypt with few, if any, positive outcomes.

Ownership stakes

Although Saudi Arabia and the UAE now appear less willing to provide substantial grants and loans, they have shown a willingness to buy state-owned Egyptian assets, including corporations and banks - something that Sisi critics argue is tantamount to selling off important, revenue-generating Egyptian institutions.

In 2022, the UAE invested in a number of Egyptian companies, and Saudi Arabia established the Saudi Egyptian Investment Company, which now owns hundreds of millions of dollars worth of shares in Egyptian companies.

The Egyptian government has also reportedly considered selling the Suez Canal to help repay debts, a possibility that has caused fear and anger among Egyptians. The government has denied it plans to sell the Suez, but for at least two reasons, fears over selling the canal might be justified.

Sisi and his tightly controlled media apparatus have tried frantically to get Egyptians to stop complaining about ongoing poverty

Firstly, as mentioned, both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have already taken ownership stakes in key Egyptian state-owned assets. Secondly, Sisi has already transferred two Egyptian Islands, Tiran and Sanafir, to Saudi Arabia, reportedly in return for continued Saudi economic support.

Sisi’s pleas of desperation have to be read in the context of other recent discourses, some of which suggest he is deeply worried about his fate, and specifically about the possibility of another popular revolt.

Sisi and his tightly controlled media apparatus have tried frantically to get Egyptians to stop complaining about ongoing poverty. In a November interview, Sisi said that “Egypt, in its current situation, cannot afford [criticism]”. He also said that “the words [of criticism] being spoken … are very upsetting”.

During the same interview, Sisi asserted that Egyptians suffer from a “lack of understanding” about political realities, and that “those who don’t know shouldn’t speak”. In multiple recent speeches, he has also commanded Egyptians to “stop with the empty talk”.

The admonitions to stop criticism are not new. For years, Sisi has lamented critical media coverage and referred to critics as ahl al-shar, or "the people of evil". In an older speech, Sisi famously said: “Do not listen to anyone but me.”

Revealing admonitions

Sisi has also used recent public addresses as a chance to describe the allegedly extraordinary efforts his government has made to rescue Egypt from catastrophe, and to imply that Egypt’s problems are too big to solve.

In an address last month, Sisi said: “I swear to God that no one would be able to do more than what we are doing.” In an earlier speech, he argued that “no president in the world would be able to solve these problems”. In other speeches, Sisi has suggested that Egypt’s problems are impenetrable, noting that past presidents were also unable to solve them.

Most telling, perhaps, are Sisi’s comments about the mass protests that began on 25 January 2011. His comments have been highly critical and represent a significant departure from earlier Egyptian discourses, which have most often celebrated the “glorious revolution” as a display of Egyptian courage and honour.

More than anything, Sisi’s remarks suggest that he is concerned about the possibility of another uprising. As I documented in a November column, Sisi has warned Egyptians specifically against protesting, saying that the path of national protest “scares me”, that it could “bring any nation to its knees”, and that it should “not ever be repeated [in Egypt]”.

These remarks, and others, suggest Sisi is deeply concerned. If he didn’t think mass protests were a realistic possibility, there would be no need to issue these kinds of regular admonitions.

It is true that Sisi has consolidated power over all state institutions, made the prospect of protesting at city squares more daunting, and created an atmosphere of fear. For all of these reasons, perhaps, past calls for protest, including those for last November, failed to generate momentum.

Nonetheless, it would be foolish to rule out the possibility of another uprising.

When the people become desperate enough, it likely won’t matter how large or intimidating the security presence around the city squares is, nor will it matter how far away the new capital city is.

Sisi’s own words suggest that even he understands this.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.