Exile: A tale of Washington's twisted role in the world

When trade economists and business pundits chatter about US imports and exports, manufactured goods versus ore and crops, and other such topics and statistics, their mechanical calculations ignore some of the most important US products: wars, refugees, border regimes, destabilisation, food dependency, environmental toxins and coup d'etats.

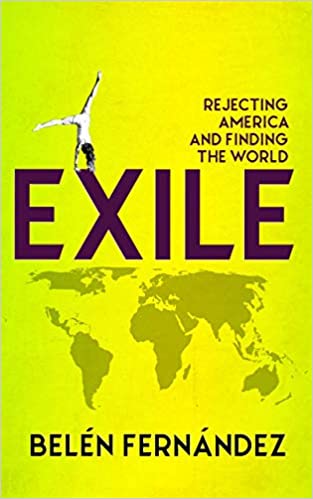

While Belen Fernandez's book Exile: Rejecting America and Finding the World is on its surface an acerbic travelogue of her many years outside the United States, it does not share that blindness to what so many people experience as the face of the US in the world. Instead, it relentlessly practices an endangered, if not nearly extinct, species of journalism: dissident anti-imperialist muckraking.

Early accounts

Fernandez begins with a stars-and-stripes-wrapped family history, tenderly poking an enormous amount of fun at her forefathers' work in the US government, counselling presidents and overseeing crimes that she then proceeds to clinically anatomise - for example, Manuel Noriega's swift conversion from US political attache in Central America to corrupt coca king as the pretext used to level Panama City.

Early accounts of elementary-school patriotic indoctrination, and of her teacher warning her pupils of how Saddam Hussein might bomb the school, cut to the sanctions regime against Iraq, which killed half a million children.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Mockery is doled out in measured dollops: US patriots, racists, war-enchanted pundits and war-persecuting presidents are frequent targets

This is not a cliche-larded meditation on the troubles of expat life, nor a saccharine story of the author finding herself in an ashram in an anonymous South Asian metropolis. It is about politics.

Fernandez steps quickly between her own familial and personal biography and the wider currents of history and of the world. Mockery is doled out in measured dollops: US patriots, racists, war-enchanted pundits and war-persecuting presidents are frequent targets.

Lesser recipients are her own and her family's occasional sillinesses. The account of her family's recoil from the anti-Muslim racism of which a post-9/11 US reeked is effective.

In the shadow of colonialism

For Fernandez, seldom does the personal stay personal. Autobiography becomes a way to discuss US foreign policy and US crimes. I liked best her chapter on Lebanon: we get nice, nugget-sized histories and sociologies of Lebanon's neoliberal sectarian system, and life in Lebanon in the shadow of the southerly colonial state.

The latter leaves a long shadow, from Palestinian-Lebanese friends unable to secure appropriate jobs or return home to Palestine, to the 2006 assault whose debris and physical aftermath Fernandez saw, to conversations peppered by the massacre of Qana or Israel's alliance with the fascist Phalange forces.

With all the absurdity of the US-Israeli prerogative to rain fire from the sky, the chapter is broken up here and there with unsightly quotations from senior Israeli military personnel promising to pummel Lebanon back in time.

The chapter on Honduras traces the country's arc from 2009 to the present: from the US-backed coup d'etat that deposed the populist Manuel Zelaya, to the subsequent murders and repression that cascaded across the country as US-backed-and-trained right-wing forces rained mayhem on a population that did not accept the coup.

Fernandez then flashes forward to the 2018 refugee caravan that wound north from Central America to knock at the gates of the US border (brilliantly mocking a military officer's depiction of god-fearing soldiers as "armed cherubs").

Humanism and the iron fist

Elsewhere, we see the toxic effects of industrial underdevelopment, through Fernandez's account of an epidemic of broken bones and rashes in Tunisia's nearly murdered Gabes oasis, its lush palms and groves withering and shrinking as a cancer-causing phosphate factory spews out chemicals - producing sparkling GDP numbers, but also ongoing declines in the health of human beings.

Exile works by example. The author's account of the lives of political and economic refugees in Malta - living in concrete pipes, going to hospitals in handcuffs - could have stopped there, with a familiar story of the barbarities of the border regime through which Fortress Europe protects the remains of its welfare states.

Instead, as Fernandez notes, "migration patterns will hold" so long as the borders apply only to "have-nots" and not to "predatory corporations or the ubiquitous military".

At a time when it has become a liberal article of faith that refugees are welcome in the US, Fernandez focuses not merely on the humanism that accepts refugees, but the iron fist that makes them. Central American refugees are refugees from US wars, US-installed neoliberalism, US-installed regimes and US-caused climate change.

While the US is serious about protecting its border with Mexico, it cares a lot less about respecting the borders of Honduras, Mexico, Venezuela and Iraq. Some borders matter and others don't, and Fernandez does not allow the reader to forget that for one moment.

A great service

Exile is not just a tale of woe. While it has become less-than-fashionable to discuss ongoing efforts to create a better world, Fernandez warmly praises the Cuban-doctor-staffed Venezuelan health clinics for the poor, and she sketches the biography of a Cuban clinic doctor who previously worked in various African countries and in Afghanistan. As the doctor told her, like US doctors, "Cuban doctors also operated in conflict zones - but to save lives."

In case after sordid and bloody case... she insists that the target of critique cannot simply be bad people doing bad things

What Fernandez does in this book is so old-fashioned, and has so quietly evaporated from the how-to guide of being a leftist journalist, that it is worth noting. In case after sordid and bloody case, roving from Tegucigalpa to Diyarbakir, Turkey, to Beirut, she insists that the target of critique cannot simply be bad people doing bad things.

People writing on places where the US is responsible for doing bad things ought to convey the US role. It is usually enormous: shipping Blackhawks and Apaches to the Turkish counterinsurgency forces, embargoing infrastructural repair and water purification equipment from a war-devastated Iraq. In reminding us of that role, Fernandez does us all - except for those profiting from such mayhem - a great service, and it there that the book's central contribution lies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.