Guarded optimism in some Iraqi quarters over Abadi

Iraq’s Prime Minister designate, Haider al-Abadi, came closer to the job when the former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki stepped aside officially yesterday. The two men have a lot in common and many are asking what kind of a difference al-Abadi can make. If he is half the negotiator he is supposed to be, then he may well make a lot.

The first positive sign was acting Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki formally stepping aside yesterday, saying that he would withdraw his candidacy and drop any legal proceedings to hinder the appointment of a new Prime Minister for Iraq. That’s a bonus: After all almost every other leader of this country has exited the job lying down.

The second positive sign is that Haider al-Abadi looks likely to be Iraq’s next Prime Minister.

Why? Because, perhaps most importantly for the present situation, it means al-Maliki won’t be.

True, not all of the bad things about Iraq’s political system are Maliki’s fault. There is plenty of corruption, nepotism, bribery, bad governance, inefficiency and sectarianism in other parts of the Iraqi political system too, and these are regularly exploited by all who work within it. But many ordinary Iraqis perceive those things to have worsened under al-Maliki. So as a symbol of all that troubles Iraq presently, it is good that he is as good as gone.

Al-Abadi’s name and history do not make him an immediately untrustworthy prospect for other segments of the Iraqi population. To reverse some of the damage done over the past eight years a lot of trust and good political will is required.

And there hardly seems to be anyone who is going to miss him. Although he got a lot of votes in the last general elections, getting the top job in Iraq has never really been about the voters, more about insider horse trading. And now al-Maliki has been as thoroughly deserted by his former allies, both inside and outside the country, as any would-be despot.

The obvious question now: Can Abadi actually do a better job? After all he has been a member of the same party as al-Maliki, the Dawa party, for just as long as the soon-to-be-former Prime Minister. This means his constituency is similar, if not the same.

He is also, as al-Maliki is, a Shiite Muslim at a time when many of Iraq’s Sunni Muslims feel disenfranchised enough by a Shiite-led government to want to form their own country. Al-Abadi also has links to neighbouring Iran, as did al-Maliki; they are openly supportive of his candidacy. And while he is an able negotiator, analysts say that up until now he hasn’t visibly differed in his attitudes and policies to al-Maliki.

Nonetheless most Iraqi journalists I have spoken with are cautiously optimistic.

“We must wait,” one Baghdad-based reporter says. “But I think he will try his best.”

“Personally I think al-Abadi will be better than al-Maliki,” says another from Mosul. “Or at least,” he pauses for thought and a wry smile, “he will make less errors.”

Maybe they just need some hope at this dark time in Iraq’s history. Then again, maybe there really are some reasons for positivity.

For one thing, having lived in the UK for a long time, al-Abadi is the graduate of a different system, both literally and metaphorically. In Iraq, if you know the right people you buy your academic degree. Al-Abadi actually graduated from the University of Manchester. He has also experienced a different political system.

He has a reputation as an experienced and able negotiator, who appears more open to compromise than al-Maliki was. For example, in 2005, he was apparently able to bring local tribes together to help rid the northern town of Tal Afar of Sunni Muslim extremists from Al Qaeda. No mean feat for a Shiite Muslim operating in Sunni Muslim territory.

Indeed reports are already filtering out that the leaders of some of the Sunni Muslim militias involved in helping the Sunni extremist group, formerly known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, gain control of places like Mosul, have sent messages to Baghdad expressing their openness to negotiations with Shiite politicians. They’re apparently offering to expel the extremists, who are becoming less and less popular due to their brutality and cruel interpretation of Islam, in return for more control over what they see as their own Sunni-Muslim-majority centres.

And this is where al-Abadi’s reaction will really count. Will he be willing to negotiate on this subject – that is, will he be willing to hand over some power to Sunni Muslim leaders in Sunni Muslim areas? Or not?

That was one of al-Maliki’s biggest problems – he ended up by refusing to share power. Rather than decentralising decision making – which was something the broad-based Iraqi Parliament seemed to want, when they passed legislative amendments to things like the Provincial Powers law, or Law 21 – he kept bringing it all back to Baghdad.

The same question is going to arise with Iraq’s Kurds. The economic success and relative peace and prosperity that the semi-autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan has, proves that decentralised power sharing can work in Iraq. Yet the Iraqi Kurdish still tussled with Baghdad over things like oil revenues and the so-called disputed territories – that is, areas that the Iraqi Kurdish say should belong to their region but which Baghdad says belong to Iraq proper.

Al-Abadi is certainly going to have trouble with this. The current military crisis, which saw the Iraqi army abandon some of the disputed territories and the Iraqi Kurdish military move into them, has meant that Iraqi Kurdistan now controls some of the disputed areas they always wanted. It’s highly likely they won’t be willing to give them up again.

One of the biggest systemic issues in Iraqi politics is the dreaded quota system. This was something first established by the US after they toppled the regime of Saddam Hussein in 2003. Parcelling out the most important jobs in politics equally to Iraq’s three biggest populations – Sunni Muslim, Shiite Muslim and Iraqi Kurdish – was meant to keep the peace. The quota system has meant that Iraq’s Prime Minister was always a Shiite Muslim, the President would be an Iraqi Kurd and the Speaker of the House would be Sunni Muslim – this same system was also used for less senior positions.

And although the quota system was never written into Iraqi legislation and the plan didn’t really work - peace was obviously not kept in Iraq - the quota system has continued to be used. Every now and then, Iraqi politicians look like they’re segueing away from this system toward real democracy – for instance, the recent nominations for Iraqi president almost bucked the trend – but then they slip back into quota mode. Which is what makes it so hard to get anything done in Iraq if you’re working within the rules – everything requires prolonged negotiation.

And perhaps that’s the key to working out the answer to the question about whether al-Abadi will do better. The systemic issues - things like the tribal culture and religion in Iraqi politics, the nepotism and the corruption – are not going away overnight, if ever.

But there is one thing that Iraq certainly needs right now and that is a lot of negotiation, much of it to reverse what al-Maliki has “achieved” so far.

Negotiations are needed to form a new government and cabinet. And these will need to be shaped in a way that assures all of the country’s stake holders that they’ll get their say and their share.

Negotiations will be needed to inspire local Sunni Muslims to rid themselves of the misguided extremists in their midst; they’ll need to feel certain that they have some power over their own destinies once those terrorists and their Caliphate is gone.

Negotiations will also be required to convince armed and dangerous Shiite Muslim militias that they too should put down their weapons; al-Abadi will also need to win over a corrupt military leadership.

Negotiations will also be necessary to bring the Iraqi Kurdish back to Baghdad’s fold, without either side feeling they’ve lost too much.

All of those negotiations are going to be extremely hard going. And obviously nothing is going to change overnight. Democracy, as they say, is a process. Although he is inheriting one heck of a mess, if al-Abadi turns out to be as able a negotiator as his reputation suggests, then maybe, just maybe, the Iraqis have chosen the right man for this terrifyingly difficult job.

- Cathrin Schaer is the Editor-in-Chief of the Iraqi current affairs website, NIQASH.org. The site publishes features and commentary in three languages – Arabic, Kurdish and English - by Iraqi journalists and writers, from right around the country.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

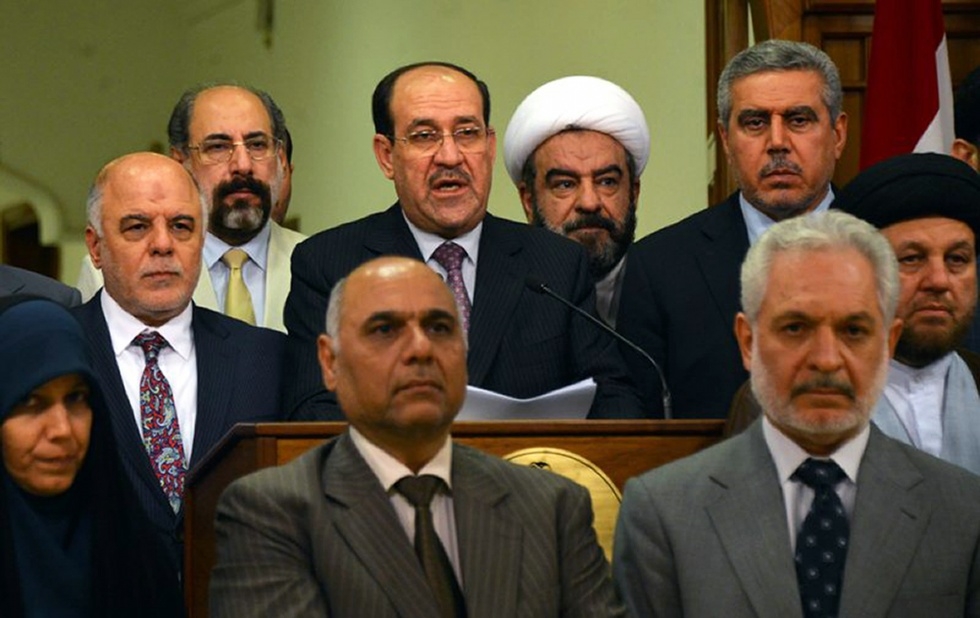

Photo credit: Iraqi Prime Minister designate, Haider al-Abadi and former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.