Can the Arab uprisings move toward a successful revolution?

Week after week, the protesters return to the squares, blockading streets and highways, attempting to tear down the barriers erected to protect the centres of state power. They face bullets, batons and tear gas. The struggle of revolutionary masses against their discredited regimes continues from Beirut to Baghdad to Algiers.

In Sudan the popular uprising overthrew the strongman Omar al-Bashir and a new transitional regime, an uneasy co-habitation of civilians and military, replaced him. The transition is suspiciously long - the agreement between the armed forces and the Freedom and Change Coalition sees a three-year period before new elections. Some fear it will never end, and the older order will be restored on a new footing, under sovereign council leader Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

In all of the four recent uprisings – Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq – an impasse has been reached between protesters and regimes

In fact, in all of the four recent uprisings – Sudan, Algeria, Lebanon and Iraq – an impasse has been reached between protesters and regimes. This is despite the many achievements in bringing down old leaders and opening up a new political space and accountability, where before fear and disengagement were the norm.

In the face of these movements, the old elites have used a combination of repression, partial concessions and prevarication in attempts to wear down popular demands for change.

Sarah Haidar, the Algerian novelist, writing for Middle East Eye, sums up the feeling that the revolution has been derailed: “The revolutionary process in Algeria lost its essence as it allowed itself to be (mis)guided by a certain class, political and social, whose concerns, privileges and designs are diametrically opposed to the real desire for emancipation which animates, knowingly or unconsciously, the greatest number.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Despite its perfectly harmonious and horizontal appearance, the hirak (protest movement) has already self-purged its most political elements, in other words the most revolting, to agglomerate around a project that is both unambitious and anti-revolutionary: the simple change of regime.”

War of position

Yet the mood of protesters on the anniversary of Algeria's mass movement last week was more optimistic. "This power will eventually give way," declared Zoubida Assoul, president of the opposition Union for Change and Progress party, "because on one hand, we have a globalised youth who lives in the 21st century, and on the other, a ruling class whose software is from the past century. But also because no government will stand without its people, and no project will succeed without the backing of the people."

Unlike the major 20th century revolutions in Russia, China, Cuba and Iran which, via armed uprisings, mass strikes and, ultimately, revolutionary violence, swept away the old elites, in the 21st century, revolution is a war of position, with leaderless protest on one side and the deep state and its gallery of discredited representatives on the other. In this new world, the endgame is hard to decipher.

Earlier in the decade, uprisings ended either in brutal counter-revolution (Egypt, Syria, Bahrain), a democratic transition (Tunisia) or a war of all against all (Libya and Yemen).

In every case, foreign powers stuck their oar in to make sure that the revolution did not jeopardise their interests: the Gulf Arab monarchies wanted stability of the old order, Israel to preserve its security ties, and the West to preserve both security and energy interests. Russia too wanted to preserve the status quo in Syria - and was prepared to achieve it with military force. This is the permanent counter-revolution hanging over all the uprisings.

Only in Yemen did an organised, armed group take up the mantle of the revolution to seize state power, at least in large parts of the territory. Critics would say the Houthis are far from the ideal vehicle for the original dream of a democratic, civil state demanded by the 2011 protesters, but then such a vehicle has been hard to find in all the region’s uprisings.

Moreover, the idea that civil society and democracy, as conceived by western NGOs and think tanks, is actually an answer to overthrowing and replacing an oligarchic state is itself something of an illusion.

As Tunisians have come to see, unemployment, regional poverty and inequality have persisted a decade since the overthrow of longtime leader Ben Ali. The landslide election of an outsider, Kais Saied, as president in October was a massive rejection of the political elite that had taken power after the 2011 revolution (much of it straight from the old elite under Ben Ali and his predecessor).

Second wave

The second wave of revolutions that broke out at the end of 2018 have intensified and deepened. And yet all of them have reached a difficult standoff. In Iran, a brutal crackdown has crushed unprecedented protests, for now at least.

From a historical perspective, the revolutions have lacked a singular ideology or organising force in the face of highly repressive state institutions that have weathered the storm of revolt, reorganised and then struck back to restore the old order – as in Egypt.

We know what the revolutionaries are against - the regime, the politicians, the existing economic order of corruption and poverty for millions.

The revolutionaries in Lebanon are understandably hostile to the existing sectarian-based politics of the leading parties and seek to end the rule by bankers that has bled the country dry. The new government of Hassan Diab appointed a banker as finance minister earlier this month, just to show nothing had changed.

In Iraq, those protesters who support Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr have, in part, expressed support for a more centralised, presidential form of government to replace the discredited, corrupt parliamentary system imposed by the US occupation.

The tension between the anti-sectarian demands of some protesters and the Shia religious base of Sadr has broken into violence in recent weeks, a sign of a possible fracturing among the protesters.

Still, the recent pro-Iran moves by Sadr has sparked a massive popular reaction among the demonstrators, who returned to the streets to reject the violence unleashed against them and Sadr’s call for segregating protests along gender lines.

Lack of cohesion

For most of the 20th century, a mixture of nationalism and socialism drove the revolutions that swept the region, as they did in much of the post-colonial world. In this century, these ideologies have been tainted by past failures and tyrannies.

The demands in all the uprisings in the region are very focused on the process and mechanics of politics and have very little focus on questions of economics or ideology

Yet the popular demand for the fall of the regime and all its representatives appears to lose its clarity in what it wants to replace this system. This is the weakness of revolutions led by a mixture of desperation and fury over economic and social injustice, but lacking a cohesive ideology to rally around.

As one frequent visitor to Iraq explained to me, the demands in all the uprisings in the MENA, including Iraq, are very focused on the process and mechanics of politics and have very little focus on questions of economics or ideology.

The demand that a new government not include any figures from the old regime – prominent in Lebanon, Iraq and Algeria – still leaves the job of finding new leaders to replace the old ruling elite.

Citizen assemblies

At some point the revolutionaries need to organise their own assemblies, perhaps chosen randomly from the population, along the lines of the citizen assembly movement in Europe.

These assemblies of the people can debate and formalise a programme, by taking expert evidence and weighing the best solutions (though this task will be fraught with difficulties), and then from their own ranks, or from a list of non-tainted candidates from the movement itself, put together an electoral list. The revolutionaries must become their own organised revolutionary government in waiting.

This is what the revolutionary parties did in the 20th century, creating what Lenin called dual power – the emergence of a new embryonic state that challenges the legitimacy of the existing state.

The new movements do not need to adhere to Marxism-Leninism, they can instead become the embodiment of the population by representing its broad class composition through a carefully chosen assembly using the sortition, or jury-style selection, system.

It can then put forward a revolutionary programme, based on careful deliberation, and choose the leaders to implement it. The last element of this process is critical – the movement must become its own political leadership with the will to take power and transform society at an administrative level, with the mass movement behind it.

Struggle for hegemony

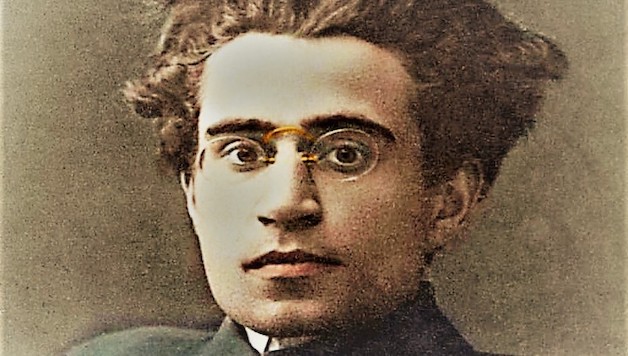

These new revolutions are engaged in a war of position - as Antonio Gramsci would have understood it - to take power from the old order and win the battle of hegemony. This happens not through violence, but through popular, ideological and cultural struggle. There is a physical element to that struggle, but the cultural and social struggle is at least as important as any street battle, which, in the end, the repressive Arab state, with its myriad forces of violence, is destined to win.

If the protesters can take this next step towards seeing themselves as harbingers of a new kind of state, rather than just opposing the old state, they can claim victory.

New models of popular democracy in its original Greek sense - rule of the people - are taking shape in places such as France, Ireland and Spain

The difficulty is that the illusion of a classical western-style representative democracy is something of a dead end. The western model has not produced an egalitarian society – it has to a large extent given power to social and economic elites, a form of plutocracy where a billionaire Donald Trump or a privileged Boris Johnson takes power on a right-wing nationalist ticket.

New models of popular democracy in its original Greek sense - rule of the people - are taking shape in places such as France, where the gilets jaunes movement has demanded citizens’ assemblies to address their demands, to Ireland and Spain. (Some have argued that these initiatives will inevitably be co-opted by the government in order to tame them and maintain the status quo.)

Democracy must be reimagined as something that comes from society itself and is directly representative of the people, not from elite political parties who largely represent capital, the state and foreign powers.

The second phase of the revolutions may be coming. As the Algerian human rights activist Fadila Chitour told MEE: "Such a massive and profound change cannot be achieved in a single year. It is imperative to continue and give yourself the means to continue."

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.