How coronavirus pandemic could expand China's footprint in Turkey

The coronavirus pandemic is hammering Turkey’s fragile economy, which was only just emerging from a crisis in 2018.

Exports and tourism have collapsed, depriving the country of foreign currency. The central bank is bleeding dollars to prop up the lira, which recently hit a record low. Turkey may soon run out of reserves. Disaster is imminent.

Many countries are relying on the International Monetary Fund to help them through the economic crisis caused by Covid-19, but Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has refused to ask for the fund’s assistance. Talks on a swap deal with the US Federal Reserve have so far not yielded results, and there is reason to doubt that Turkey would meet the criteria for such an arrangement.

Threat of sanctions

Moreover, relations with Washington are strained due to Ankara’s acquisition of the Russian S-400 missile defence system. The US Congress is currently mulling sanctions, the last thing Turkey needs as its economy struggles. In an apparent effort to assuage US anger and gain financial support, Turkey recently delayed activation of the system, planned for April.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Erdogan also went on a charm offensive, sending medical supplies and penning a letter to Trump. But Ankara seems intent on activating the S-400 eventually, as one of Erdogan’s top advisers confirmed last month, effectively killing any prospect of a meaningful improvement in ties.

Ankara's relations with Beijing, frosty for decades, have improved rapidly in recent years as Turkey has gravitated away from its Nato partners

Turkey is now turning to other countries for help. Swap deals with Japan and the UK are reportedly in the pipeline. Ankara is also in talks to expand facilities with Qatar and China; on Wednesday, Turkey tripled its existing local currency swap deal with Qatar to $15bn. In 2019, China extended a $1bn swap line to Turkey after US sanctions pushed the lira into freefall the previous summer.

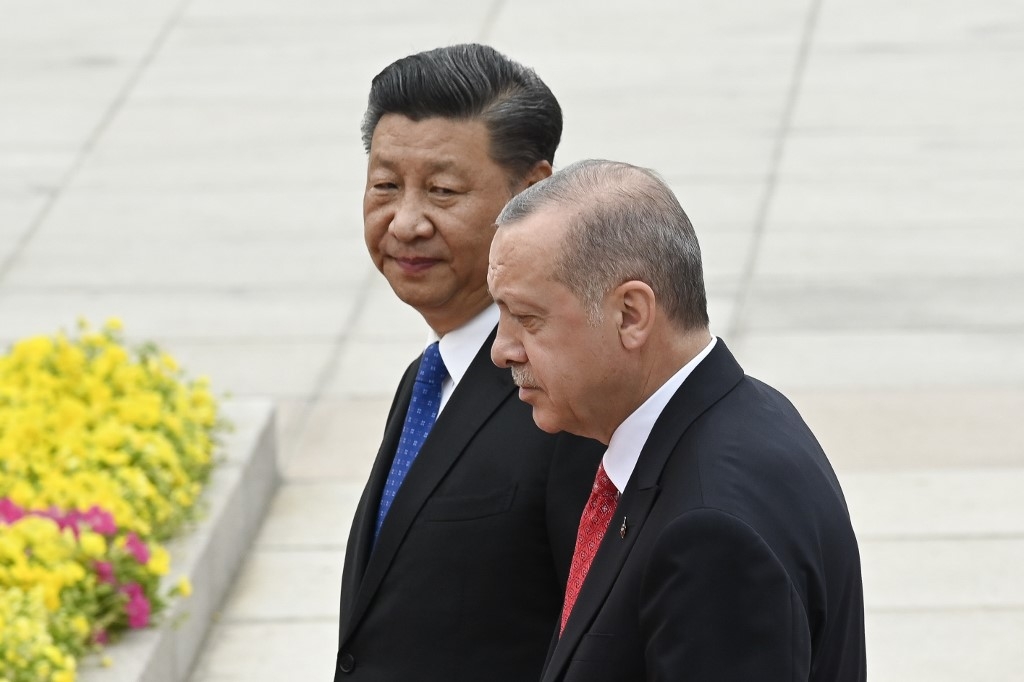

Ankara’s relations with Beijing, frosty for decades, have improved rapidly in recent years as Turkey has gravitated away from its Nato partners to embrace non-Western countries, including Russia. Now, as Turkey’s economy collapses and tensions with Washington persist, it may be forced to rely even more on China’s support.

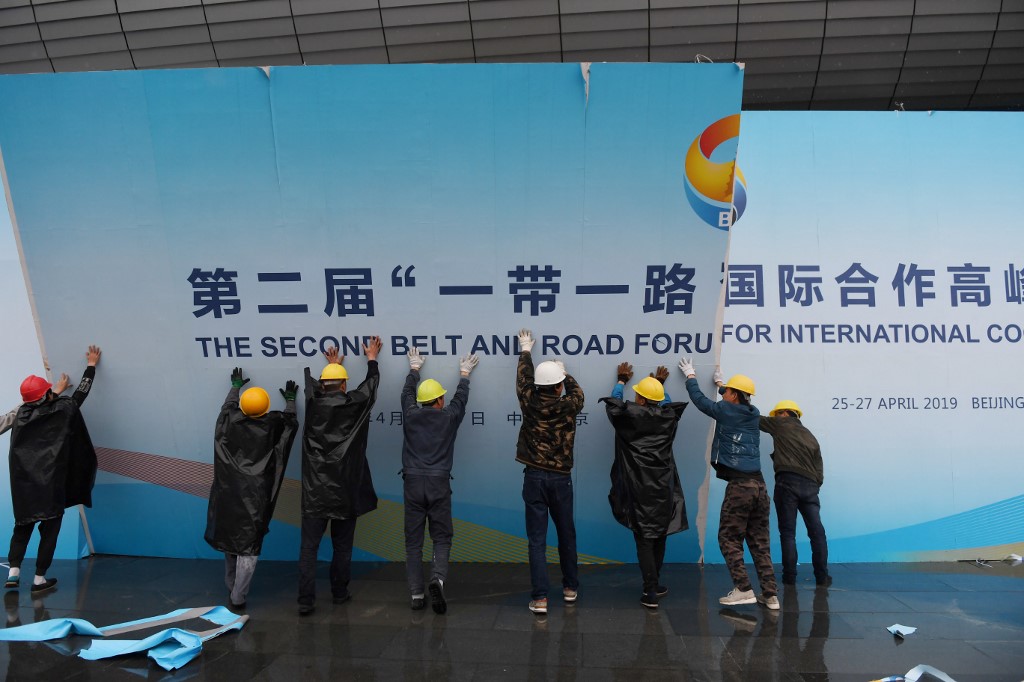

In 2010, the Chinese premier visited Ankara and concluded a strategic cooperation agreement. Since then, trade has increased significantly, with a flurry of big-ticket infrastructure deals. Erdogan has visited Beijing a number of times, including in 2017 for a large international forum devoted to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Trans-Eurasian connectivity

The BRI links Europe and Asia through a vast network of rail and maritime routes. Given its geographical location between east and west, Turkey is well-placed to play a role, and some of its own infrastructure plans align with China’s grand vision of trans-Eurasian connectivity. The Middle Corridor transport project, for example, connects Turkey with Central Asia by rail and ferry.

In a 2015 memorandum, Erdogan and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, agreed to integrate that initiative into the BRI. And there has been progress developing the Middle Corridor, with a Baku-Tblisi-Kars railway coming online in 2017. The first train to cross from China to Europe along the corridor transited through Istanbul’s Marmaray tunnel late last year.

Then there are ports. In 2015, a Chinese consortium purchased Kumport, Turkey’s third-largest container terminal, near Istanbul, and three more ports are being eyed at Mersin, Candarli and Filyos. Chinese companies are reportedly keen to participate in Erdogan’s controversial Kanal Istanbul project, which will open up a new waterway to rival the Bosphorus.

A Chinese consortium also bought the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge over the Bosphorus and its associated motorway, connecting Istanbul to the new airport. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China was in talks to refinance loans worth around $6bn for the operation of the airport. It has also pledged $3.6bn in loans for Turkey’s transport and energy sectors.

China is involved in Turkey’s nuclear development, building its third power plant. On the telecoms front, Chinese tech giant Huawei is constructing a 5G network and has a research and development centre in Istanbul - its second-biggest in the world - while ZTE purchased Turkish company Netas several years ago. In the realm of e-commerce, Alibaba bought a stake of Turkey’s online retailer, Trendyol, in 2018.

China's persecution of Uighurs

Then came the news this March, drowned out by the coronavirus pandemic, that China’s main insurance company, Sinosure, had concluded a big deal with Turkey’s sovereign wealth fund (TVF) to provide financing and guarantees to projects. TVF controls interests in gas, mining, finance and other key areas.

Sino-Turkish relations were held back in the past by the presence of thousands of ethnic Uighurs in Turkey. The Uighur exiles are Turkic Muslims who fled persecution in China, where over a million have allegedly been rounded up and detained in concentration camps.

For decades, Turkey offered the Uighurs refuge, angering Beijing. But that may now be changing. Uighurs have reportedly been arrested and harassed by Turkish authorities.

A draft extradition treaty between Turkey and China was signed in 2017. Erdogan had once spoken out against Chinese persecution of the Uighurs, but he has become conspicuously silent.

Yet, despite the rapid strengthening of bilateral ties, there is still a long way to go. The relationship is one of “ebb and flow”, as Turkish China expert Altay Atli writes, where progress is disrupted by periodic crises. For example, in early 2019, amid warming relations with Beijing, Ankara abruptly slammed China’s policies in Xinjiang.

There are other problems. Trade last year was far below the target of $100 billion set for 2020 and heavily lopsided in China’s favour, exacerbating Turkey’s current account deficit. The Middle Corridor is cumbersome, crossing multiple borders and at least one stretch of sea. China’s preferred overland route to Europe remains the Northern Corridor via Russia. In any case, most freight travels by sea, which is cheaper than rail (although the coronavirus has given railway transport a temporary boost).

Balancing east and west

And for all its problems with Washington, Turkey remains highly dependent on the West. Europe and North America have consistently accounted for far more of Turkey’s foreign direct investment inflows than China.

In 2019, 4.8 million tourists from Germany and 2.5 million from Britain visited Turkey, compared with around 400,000 Chinese visitors.

Despite Erdogan’s repeated threats to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, Turkey gets more influence and security from its Nato membership than it would from the fledgling, Beijing-led group. And China is unpopular with Turkish people: polling shows that a minority of Turks have a favourable view of the country. This became apparent in Istanbul last year, when signs to mark China’s national day provoked uproar.

Turkey is not trying to 'pivot to Asia' to cut ties with Western countries and substitute China for the US and Europe, but to diversify its foreign relations

Turkey is not trying to “pivot to Asia” to cut ties with Western countries and substitute China for the US and Europe, but to diversify its foreign relations and maintain a balance between east and west. Such a balance, however, is hard to achieve, as US anger over Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 system shows. And with US-China tensions escalating, Turkey may be forced to pick sides.

The Trump administration has adopted a hawkish approach to China, trying to drive Huawei out of the UK and other countries, for example. But it has been relatively quiet about Beijing’s growing influence in Turkey, a key Nato member state.

That attitude may prove unsustainable. Eventually, the US and its allies will have to confront the reality that one of their most important regional partners is moving further and further into China’s orbit.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.