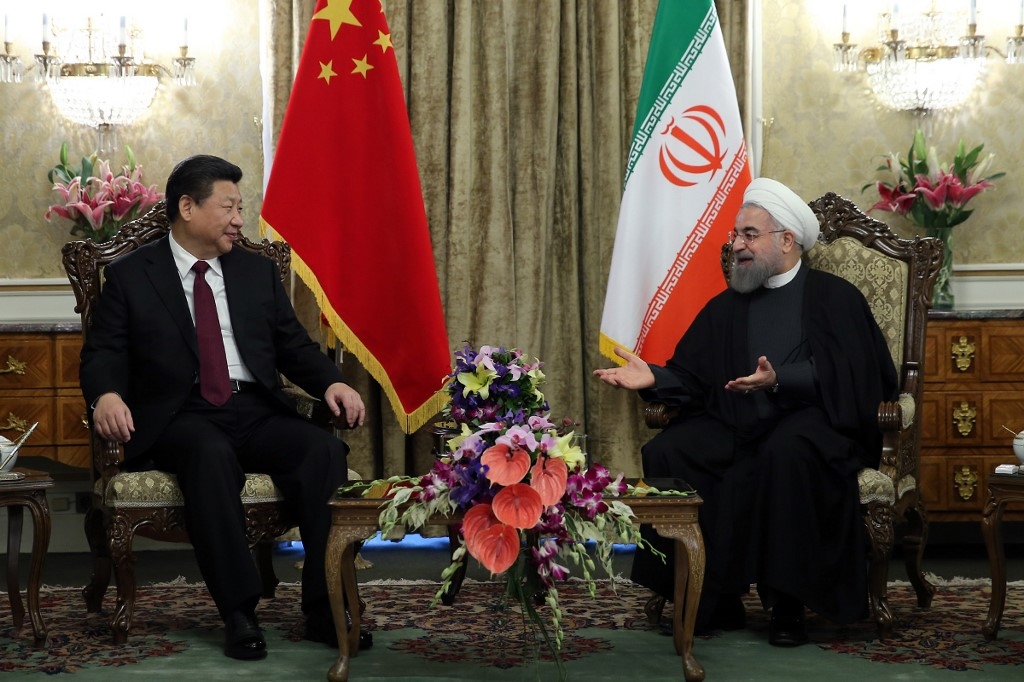

How Iran-China deal could alter the Middle East's balance of power

The Iranian government has reportedly approved a draft 25-year deal with China on economic and political cooperation. Iran’s foreign ministry spokesman, Abbas Mousavi, said it was a proud moment for Iranian diplomacy.

Tehran has not revealed the full details of the agreement, but a previous report by the Petroleum Economist suggests that Iran is set to grant huge concessions to China, including significant discounts on oil and gas, and the ability to delay payments for up to two years and to pay in soft currencies.

China's more pronounced interest in Iran should alert the US to review its past approach towards Tehran

China would also be granted first refusal on opportunities to become involved with any petrochemicals projects in Iran. If implemented, this agreement would make Iran highly dependent on China economically, while Beijing would acquire a large and secure source of energy, as well as a foothold in the Gulf.

Already, there have been rumours in Iranian media that Tehran has ceded Kish Island to Beijing. While such rumours are likely false, Iran can certainly offer China military facilities in its Gulf ports.

The deal also provides for up to 5,000 Chinese security personnel on the ground to protect Chinese projects, an element that seriously undermines Iran’s political independence. This agreement promises to greatly enhance China’s position not only in the Middle East, but also in Central Asia and the Caucasus.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Through Iran and the Caucasus, Beijing would have a land route to Europe and even the Black Sea, provided Georgia allows it access to its Black Sea ports.

The advantage for Iran, if China lives up to its commitments, is the infusion of a significant amount of cash into its economy, especially its energy sector ($280bn) and manufacturing and transport infrastructure ($120bn.) Such an infusion would certainly help to revive Iran’s economy and create more jobs - and, in turn, bolster the Islamic regime and ease domestic opposition.

Pivot to the East

But the fate of the deal is not yet clear, as it still has to be approved by parliament. When news about the agreement first appeared in Iranian media, many commentators expressed concern that it could make Iran excessively dependent on China, noting that after the revolution of 1979, Iran did not end its decades of dependence on the US to become a semi-colony of China.

I previously likened the agreement to the infamous Reuter concession of 1872: the Times of London then called that deal, between British banker Baron Julius de Reuter and the king of Persia, the largest surrender of a country’s resources and sovereignty to a foreign concern.

A major reason for Iran’s shift towards China and other Asian countries, known locally as the “pivot to the East”, has been the failure of Iran’s repeated efforts, beginning with the administration of Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani, to expand economic relations with the West as a prelude to better political ties.

The latest of these overtures happened after the signing of the nuclear deal in 2015. Iran offered to buy Boeing and Airbus aircraft, saying it welcomed American and European companies - including energy companies, such as Total - into the country. The response to Iranian overtures, however, was not positive.

In 2018, US President Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear deal and imposed new and crushing sanctions on Iran, including on the sale of its oil. His move convinced even many moderates in Iran that Washington was not interested in improving relations, and instead wanted regime change in Tehran.

Diehard opponents of improved Iran-US relations got a second wind, seeing in China a potential saviour and a shield against future US pressure, including at the UN Security Council.

Reducing tensions

If the Iran-China agreement is implemented, it would revive Iran’s economy and stabilise its politics. Such an economic and political recovery would improve Iran’s regional position and perhaps incentivise adversaries to reduce tensions with Tehran, instead of blindly following US policies. Arab states could rush to make their own special deals with China.

Moreover, by giving China a permanent foothold in Iran, the deal would enhance Beijing’s regional position and undermine US strategic supremacy in the Gulf. This could also enhance China’s position internationally.

But the US could prevent such a shift by returning to the nuclear deal, lifting sanctions, and allowing European and American companies to deal with Tehran. An immediate effect would be the revival of moderate forces in Iran, and in the longer term, it would lead to better political relations.

By pursuing an entirely hostile policy towards Iran, the US has limited its strategic choices in Southwest Asia and thus been manipulated by some of its local partners, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE. China’s more pronounced interest in Iran should alert the US to review its past approach towards Tehran.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.