How the Syrian war resulted in Erdogan’s Istanbul defeat

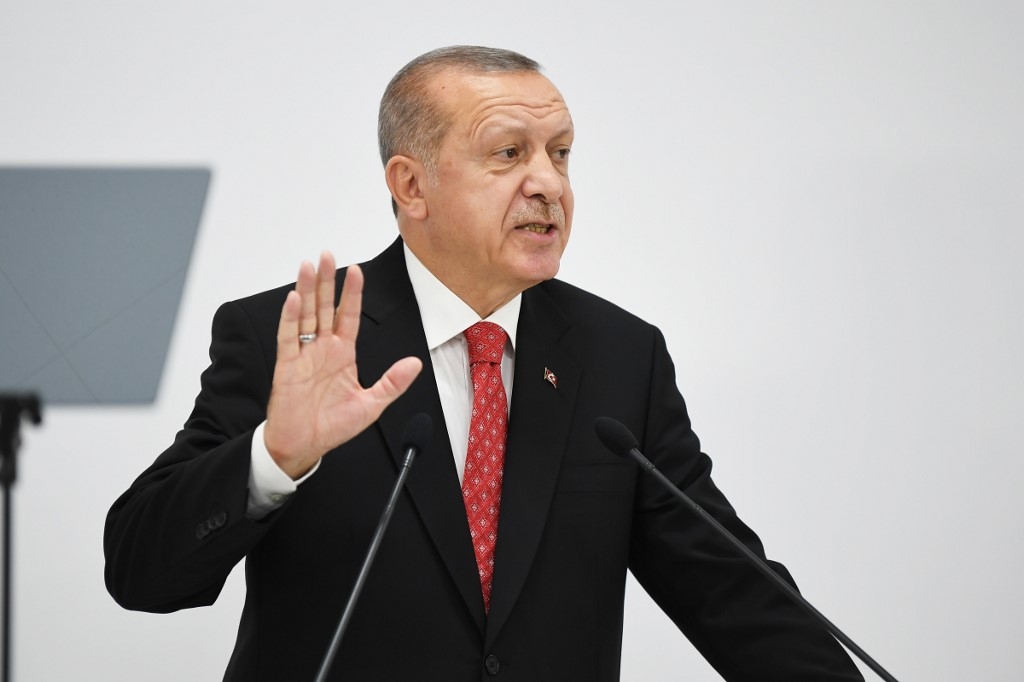

As Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the AKP reel from their first loss in Istanbul in 25 years, pressure and criticism have been mounting on multiple fronts, including from two founding AKP members, former president Abdullah Gul and former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu.

It is clear that the Republican People’s Party (CHP), along with Turkey’s Kurds and Christian community, used the Syrian war as a tool to defeat Erdogan in the polls.

The start of Erdogan’s troubles can indeed be traced to the outbreak of Syria’s civil war. Turkey was once seen as the model of a modern Muslim democracy.

Familial ties

Erdogan made Turkey’s integration into the Arab world a priority, and the pivot of this new outreach was his relationship with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, with whom he forged close familial ties, calling him his brother.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

As Assad - with the help of Russia and Iran - reasserts himself in the Arab world, Erdogan’s rivals - including Egypt, the UAE and Bahrain - are all reaching out to Damascus to push Turkey out of Arab affairs.

And while the Syrian regime had previously reversed course and played a pivotal role in supporting Ankara’s fight against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), that alliance is now in tatters, with Turkey caught between US, Russian and Kurdish diplomacy.

Syrians have never forgotten that historic lands belonging to them were, in their view, usurped by Turkey

Moreover, news of a newly formed Armenian unit joining the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to take on the Turkish military echoes a historic clash between Turks, Arabs, Armenians, Greek Orthodox and Kurds.

The borders set out in 1938 have always been contentious, and forces are once again uniting against the Turkish incursion into historic Syrian land.

The Syrian regime has played all these cards against the Turkish president, who, according to some analysts, appears to have misread the history of grievances on the Syria-Turkey border.

Syria has not only caused problems for Erdogan with other Arab states and the West, but it has also affected his domestic electoral success.

Turkey’s frontline

In a 2010 election rally in Gaziantep, during the peak of Erdogan’s close ties with Assad, the Turkish leader spoke of his brotherhood with Assad, and how it was helping to heal a decades-old rift between Ankara and Damascus. Syria had long supported Kurdish, Armenian and other leftist groups against the Turkish state.

In her book Fezzes in the River, author Sarah Shields explains that in 1936, Turkey had made controlling the border towns of Iskenderun, Gaziantep, Antakya, Mardin and Urfa a major priority. A lot of these cities came under the jurisdiction of Aleppo province and were deemed to be Syrian. A controversial 1939 referendum brought Hatay province under Turkish control.

Syrians have never forgotten that historic lands belonging to them were, in their view, usurped by Turkey. These cities, not by coincidence, became a frontline for Turkey in the current war.

In (Re)constructing Armenia in Syria and Lebanon, author Nicola Migliorino details how cities such as Aleppo, Homs and Deir Ezzor in modern-day Syria became bastions of what was left of the Armenian communities driven out a century ago. They had every reason to back groups fighting Turkey, and Syria exploited this to its full advantage, along with its support for the PKK.

In 2004, Assad upended decades of Syrian-Turkish mistrust over the border by becoming the first Syrian president to visit Ankara. He ultimately accepted Turkish sovereignty over Hatay and laid the foundations for ending all support to Kurdish, Armenian and leftist groups against the Turkish state.

Today, however, Erdogan has been unable to contain criticism - both from his own party and from the opposition - over the fallout of the war in Syria. Issues related to the Kurdish peace process, the economic burden of Syrian refugees, and the cost of the Turkish military encroachment came up repeatedly in the lead-up to the elections.

Assad’s political future

Erdogan and the AKP are now openly saying they would tolerate Assad if he won a democratic election, marking a complete U-turn in policy. They are also admitting intelligence contacts between the two countries.

Furthermore, Erdogan has looked to appease Kurds by allowing jailed Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan to speak through letters. This is the same Ocalan who was once supported by Damascus, and who is now saying that there must be talks with Assad for a peaceful end to the Kurdish problem on both sides of the border.

Armenians and Syriac Christians both oppose further Turkish operations in the border region. Members of Antakya’s Alawite community have also supported Assad over Erdogan, further outlining how the border communities side with Syria, primarily due to historical grievances.

Erdogan's giving in to Ocalan and opening up dialogue with Assad have demonstrated how Damascus has used such grievances to impressive effect. The CHP, meanwhile, has suggested that Turkey should not be fighting the war in Syria, and called for dialogue with Assad.

During the recent election campaign, there were AKP attempts to divide the Kurds by using Ocalan as a pivot, but the party could not capitalise on this, given the ongoing operations in Syria.

The CHP’s success has much to do with the economic burden of Syrian refugees, an increasingly divided Turkey, a deadlock on the Kurdish peace process, and tensions with Turkey’s neighbours.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.