India threatens new gendered war on Muslim community

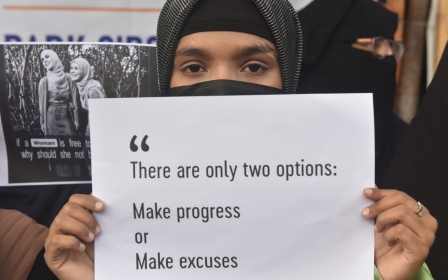

As India’s incumbent prime minister, Narendra Modi, prepares to run for a third term next year, the Muslim female body has yet again been turned into a focus of the country’s communal politics.

Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), along with affiliated radical Hindu groups, has revitalised attempts to advance legislation that would further regulate the lives of Muslim women.

This includes the Uniform Civil Code (UCC), a controversial proposal that would bring personal laws governing various religious groups under a unified common law.

On 14 June, the 22nd Law Commission of India issued a notice seeking comments and opinions from the public and religious organisations on the UCC within 30 days.

India’s home minister, Amit Shah, recently held the first high-level meeting on the UCC, sparking speculation that the government may introduce the bill in the forthcoming session of parliament. Indian media have also reported that the country’s Law Commission was considering starting work on a UCC bill.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The UCC runs counter to India’s existing personal law system, according to which certain family and property matters - such as marriage, divorce, adoption and inheritance for Hindus, Muslims, Christians and others - are governed by their respective religious laws.

The implementation of the UCC, along with the revocation of Article 370 in the disputed Kashmir region and the construction of the Ayodhya Ram Temple, have been core demands of radical Hindu nationalists. The UCC issue was also part of Modi’s poll manifesto in the 2019 national elections and the recent vote in southern Karnataka state.

In March, the Indian Supreme Court closed a batch of petitions demanding a UCC, noting that such issues were for parliament to decide.

Weaponising gender discourse

Adopting a UCC in India’s religiously pluralistic society would effectively set in motion the abolishment of Islamic personal laws governing Muslim family matters, while recodifying the customary laws and rituals of India’s various tribal communities.

Critics contend that it would undermine India’s social and religious fabric and serve as a tool for the creation of a unified Hindu nation. This belief is shaped by the Hindutva narrative that one way to deal with the “disruptive” presence of Muslims in India is to assimilate them into a “universal” Hindu social order.

Muslims have also expressed concerns that the UCC could be used to disrupt their way of life, forcing them to conform to Hindu norms embedded in national law.

Over the past century, the 'Muslim woman question' has been central to the supremacist project of India's militant Hindu groups

Conversely, some gender rights activists support the idea of a UCC, which they argue could help end discrimination against women. This type of code has long been portrayed as a legal reform to outlaw practices such as polygamy, which the Hindu right-wing has wrongly asserted to be a common Muslim practice (despite the 2006 National Family Health Survey, which showed that only 2.5 percent of Muslims engaged in polygamy).

“There are some people in India who thought they can marry four women. That was their thinking. But, I say, you will not be able to do four marriages. Those days are going to come to an end,” a senior BJP leader in the state of Assam, Himanta Biswa Sarma, said last month, asserting that the UCC would be implemented across India.

Hindutva outfits have often cited polygamy in the context of the now-outlawed “triple talaq” Islamic instant divorce, aiming to portray Muslim personal laws as “regressive” and in need of urgent reforms.

But as Indian feminist scholar Nivedita Menon has argued, the UCC has nothing to do with gender justice, and is entirely part of a Hindu nationalist agenda: “A just UCC would have to restructure the assumed heterosexual basis of marriage as an institution. But of course, neither justice nor gender parity is the real objective of a UCC, as we have seen.”

History of resentment

Over the past century, the “Muslim woman question” has been central to the supremacist project of India’s militant Hindu groups. The Muslim female body has been used as a site for retaliatory civilisational violence, becoming a key focus of the Hindutva discourse.

During British colonial rule, Hindu law was criticised, and subsequently reformed, in the context of practices such as child marriage, burning of widows, and prohibition on widow remarriage. Historian Purushottama Bilimoria has said that for Hindu nationalists, a separate set of personal laws for Muslims meant that Hindus alone were enduring the “burden of the regulatory and reformative agenda” under the “secular state”.

After revisions to Hindu personal laws in the 1950s, these laws began to be perceived as more gender-just, while Muslim personal laws were still seen as “primitive” and “uncivilised”. Hindutva groups began pushing for reform of Muslim laws in the 1980s during the Shah Bano case, wherein an Indian court disparaged Muslim personal laws in granting a Muslim woman higher post-divorce support.

The ruling echoed the Hindutva narrative, which has maintained that the Muslim family is a loose entity where women’s honour is not respected, and where men practice polygamy and attempt to lure Hindu women into their fold. Such discourses have manifested in the anti-Muslim conspiracy theory known as “love jihad”, whereby Muslim men allegedly pursue Hindu women to convert them to Islam.

Despite zero proof that love jihad exists, Hindu nationalists continue to claim that it is used as a tool for religious conversion. In February, the chief of a prominent Hindu group threatened to abduct Muslim women to counter this practice: “If we lose one Hindu girl to ‘love jihad’, we must trap and lure 10 Muslim women in retaliation … We must protect our religion from external forces.”

Scholar Runa Das has said that the “woman question” was pivotal to the Hindutva project, with upper-caste Hindu women seen both as objects of male Muslim lust and as custodians of the national honour. The BJP’s discourse has also focused on this notion as part of its efforts to rebuild a Hindu nation.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.