Invading Afrin: The missing piece of Turkey's Syria strategy

Exactly one year ago this week, Turkish troops crossed the border into Syria and began Operation Euphrates Shield, a military expedition which may have originally been intended to reach Aleppo and Manbij but ended up confining its forces to just 1,620 sq km close to its border. For the past six months, there have been periodic rumours that Ankara is contemplating a second operation, one that was even being given a name, Operation Euphrates Sword.

This week, Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan brought the prospect of a second intervention a bit closer briefing journalists on his return from Jordan. The president warned that Turkey would not allow a takeover in the isolated northwestern Syrian district of Afrin by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), a Syrian Kurdish group in control of a line of self-proclaimed cantons along that country’s frontier with Turkey, “to emerge as the dominant factor in Afrin” and then perhaps attempt to carve out a “Kurdish corridor” from Iraq to the Mediterranean.

In fact, the PYD has already put down strong roots in Afrin. A Kurdish corridor from Afrin to the sea looks unlikely as it would mean going over either Turkish territory or travelling south over the Syrian opposition-controlled district of Idlib. Since January 2014, the town has been governed by Hevi Ibrahim Mustefa, a woman PYD member described as "prime minister".“Afrin simply stands out as the missing piece of the puzzle in Turkey's security conundrum regarding the Syrian opposition's struggle,” the pro-government Daily Sabah wrote in July.

Guess who's coming to Ankara

Limited actions against Afrin are already happening. Since the night of 18 August, reports of Turkish bombardment have been coming out of the town.

The rest of the world can only guess what is being thrashed and whether Turkey can take advantage of the rivalries between the US, Iran and Russia

To do more than that, Turkey would have to square whatever it does with the other outside powers on the ground in Syria. These are the US, which is a close military ally of the PYD and is fighting alongside them to take Raqqa from the Islamic State (IS) group; the Russians, allies of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, who would like to clear the radical Syrian opposition out of Idlib; and the Iranians, also allies of Assad.

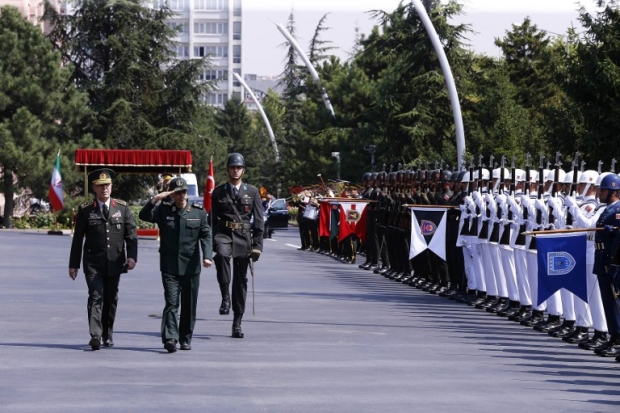

So a series of high-level military visitors has been passing through Ankara and talking to Erdogan. The Iranian chief of general staff, Mohammad Bagheri, was in Ankara for three days last week. Then came US defence secretary James Mattis on Wednesday this week. Finally, the Russian chief of general staff, Valery Gerasimov, is also expected in the Turkish capital this week.

Russia and the US are probably reluctant to ditch the ‘Kurdish wild card’ in Syria completely or to allow Turkey to take a wider swathe of Syrian territory, but relations with Turkey are of first order importance in several ways for all three.

Offers on the table

Each, therefore, is likely to want to give Turkey something - but less than it is asking. On the key question of military action, it looks as if no one wants a new Turkish incursion into Syria. Iran may be prepared to help Turkey fight the PKK which is a common threat to both, but the idea faces some opposition in Iran.

Despite a growing climate of hostility with Turkish newspapers accusing the US of massacring civilians in Raqqa, the US still sets a very high price on its ‘awkward but necessary’ relationship with Turkey, one that might just be high enough to mean ditching its Syrian Kurdish allies once their role in defeating IS is accomplished.

While in Ankara, Mattis let it be known that the US is willing to give Turkey more help against the PKK, probably in the form of signals intelligence and equipment. Since Turkey is currently bringing the whole of the southeast under tight control, this means less than it once would have done.

The US will also try to force the PYD and its military arm, the YPG (People's Protection Units), to distance themselves from the PKK - but given that a good many YPG fighters are, in fact, Turkish nationals from Turkey who are members of the PKK, this is probably not realistic.

As for Russia, Turkey’s anxiety is that if its forces move into Afrin, Russian and Iranian forces may respond by taking Idlib, and expelling the militant Islamist Syrian opposition Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) forces who currently control the town. That would be another setback for the Ankara-supported Syrian rebels and an advance for the Assad regime.

Perhaps to forestall this, Turkey is reported to have suggested to the HTS, a former al-Qaeda affiliate, that it disband - doubtless to camouflage a new entity. HTS is in any case facing local opposition already. This all looks like a very shaky basis for any deal between Ankara and General Gerasimov when he arrives in Ankara.

'Suddenly one night'

Nonetheless, when Erdogan says Turkey will do something, it usually happens. Some months back, he warned the Syrian Kurds in the words of an old song that Turkey's forces "might come suddenly one night". If a full-scale incursion cannot get a green light from the other powers in Syria, then the alternative may be to step up gradually escalating cross-border attacks while ensuring that no one comes to the aid of the Kurds.

Afrin, however, is only one part of a huge jigsaw of Kurdish conflicts that Turkey faces, one stretching 1153 kilometres (717 miles) along Turkey’s borders with Syria and Iraq. Apart from the other Rojava enclaves in Syria, in Iraq, Turkey faces a challenge from the Kurdish Regional Government of Massoud Barzani, which plans to hold an independence referendum on 25 September.

The one place that Ankara can extract just a little comfort is paradoxically in the fight against the PKK in its own troubled southeastern provinces. At enormous effort and cost, a series of harsh sweeps seems slowly but surely to be bringing the entire region back under full control, eliminating PKK terrorist fighters and arms caches in a series of massive operations.

The death toll is still high – around 20 soldiers, police, and others each month - and there is no political settlement but, as a report from the International Crisis Group showed this week, the violence has decreased since last year and the direct challenge is receding. Ankara is likely to take this as an indication that if it perseveres, it will get what it wants.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A soldier gestures as Turkish army tanks drive to the Syria-Turkey border town of Jarabulus (AFP)

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.