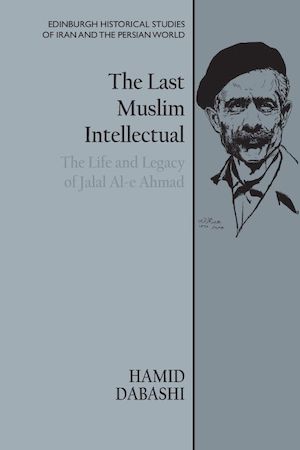

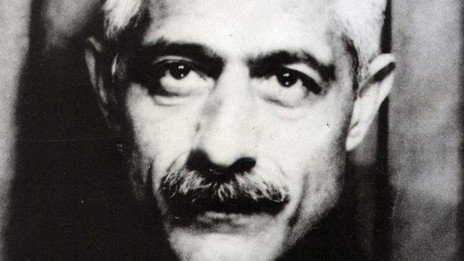

Jalal Al-e Ahmad: The last Muslim intellectual

Jalal Al-e Ahmad (1923-69) was the "last Muslim intellectual". At least, that's the claim I make in my latest book, which explores the life and legacy of the towering Iranian critical thinker.

This was a deliberately provocative title, intended to draw attention to the work. But it also relies on an argument embedded throughout the volume - one that turns the writing of an intellectual biography into a potent claim on the future of Muslim critical thinking.

In the book, I place Al-e Ahmad next to Frantz Fanon, Aime Cesaire, Leopold Sedar Senghor and Edward Said. The argument thus required rethinking the significance of a Muslim critical thinker in larger global terms.

Al-e Ahmad was not chasing after any lost self; he was aiming to decolonise critical consciousness

How could any Muslim thinker be called “the last Muslim intellectual”? How do we know whether other, more commanding Muslim intellectuals will emerge in the near or distant future?

The full range of Muslim critical thinkers, from Morocco to India, makes any such claim dubious, if not altogether ludicrous. But there was some method behind my provocation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Let me begin with the epithet “Muslim”. Al-e Ahmad was born and raised in a prominent Shia clerical family. His father was a leading member of the Shia clergy, as were other members of his family. He, too, was meant to go to Iraq and study in a Shia seminary. But his agitated soul was drawn to the more adventurous aspects of his time.

Early in his youth, Al-e Ahmad was drawn to militant secularists, such as Ahmad Kasravi, and ultimately to the pronounced socialism of the Tudeh Party. He rose in their ranks, and at some point became the editor of their newspaper.

But soon after the Allied invasion and occupation of Iran during World War II, and the heavy-handed Soviet interference in Iranian affairs, Al-e Ahmad and many other independent-minded intellectuals left the communist Tudeh Party, without abandoning their socialist ideals.

Through the thick and thin of his political career, Al-e Ahmad remained a self-confessed Muslim thinker, in the broadest and most self-conscious way. Almost single-handedly, he redefined what it meant to be a Muslim in the world - aware, conscious, engaged and receptive.

Restless soul

As a Muslim, Al-e Ahmad was a restless soul - not just in politics, but particularly in his moral imagination, literary taste, critical thinking and sense of the sacred. After he abandoned his father’s wishes for him to become a cleric, and unbeknownst to his family, he opted to pursue a more contemporary, state-sponsored public (misunderstood as “secular”) education.

But the turmoil of his homeland soon drew him to the political predicament of a young, inquisitive mind. After his initial attraction to Kasravi and the Tudeh Party, his restless soul sailed towards less charted territories. He was reenacting what it meant to be a Muslim in the world.

Al-e Ahmad’s most famous text is Gharbzadegi, usually translated as “Westoxication”, in which he sought to offer a prognosis for a colonised mind.

The Muslim world, the colonised world, and Iran are shown to be sites of this Gharbzadegi, where thinking, acting and the very lexicon of collective consciousness have been Europeanised, mesmerised, westernised - in short, colonised.

A thick layer of false consciousness had overcome the very condition of thinking. Al-e Ahmad was not chasing after any lost self; he was aiming to decolonise critical consciousness. This short treatise was the subject of intense debate, and has had enduring significance since its publication in the early 1960s.

Al-e Ahmad’s response to the colonised mind was intense intellectual engagement with the vital issues of the time in relentlessly critical prose, including literature.

Throughout his short but fruitful life, Al-e Ahmad remained committed to literature and produced some of the most popular works of fiction of his time, chief among them The School Principal (1958), an autobiographical critique of public education.

Ideological force

Al-e Ahmad’s post-Marxist turn to existentialism, which led to a sustained period of translations from European and Russian sources, including the seminal works of Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and Fyodor Dostoevsky, must be read in the same vein. Through these translations, he was reliving a critical consciousness outside of his own immediate life and heritage.

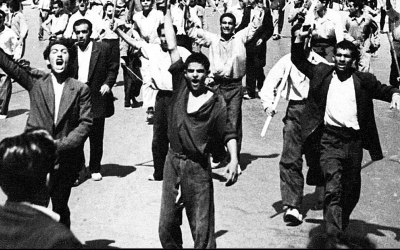

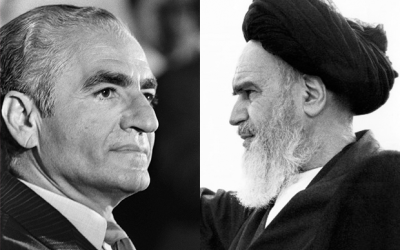

After the failed June 1963 uprising led by Ayatollah Khomeini (a dress rehearsal for the 1979 revolution), with which he identified, Al-e Ahmad wrote a major study on the services and treacheries of public intellectuals, heavily influenced by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci. By this time, Al-e Ahmad was convinced that leftist movements that were bereft of local and regional rootedness were destined to fail.

In this respect, he was the forerunner of perhaps the most potent ideological force of the 1979 revolution, Ali Shariati, with whom he had a brief encounter in the holy city of Mashhad.

Shariati was a convinced and convincing ideologue, a visionary Islamist. Al-e Ahmad was too much in the sun, too self-doubting, too much drawn to “on the other hand” - he was like a bee always attracted to the next flower. He made of his nomadic mind a proverbial truth.

After his brief affiliation and subsequent departure from the Tudeh Party, Al-e Ahmad remained committed to the cause of socialism. Precisely in that period, he made the monumentally stupid decision to travel to Israel on an official invitation and to write a deeply misguided account defending the Zionist project.

Soon after the 1967 war, however, he realised the inanity of his hurried impressions, and wrote a second part in which he denounced Zionism and its US and European supporters. The two parts were so diametrically opposed that some even doubted the authenticity of one or the other.

But they were both his, reflecting his agitated, restless, impatient and impressionistic way of thinking. He was not consistent. He was real. Before his detractors had collected the prose to criticise him, he was already somewhere else. He compared himself to a horse who could hear the tremors of a pending earthquake, rather than a seismographer measuring it scientifically.

The 'four qibla'

Al-e Ahmad’s most enduring works were perhaps his ethnographic monographs on Iranian localities, such as Kharg Island or the village of Owrazan, followed by his travelogues, the most important of which arose from his Hajj pilgrimage.

From his travels to the Soviet Union, the US, Mecca and Jerusalem, Al-e Ahmad had intended to publish a fourfold account of the “four qibla” of his time. To these four destinations, he was drawn with equal intensity. The result was a critical consciousness of the world around him that became the critical consciousness of the world around his nation.

Good or bad, pleasant or nefarious, critical or implicated, Al-e Ahmad represented a moment in a Muslim's intellectual engagement with the world

Al-e Ahmad’s most important and potent works of prose were delivered in the form of short essays, a mode he perfected. He did for Persian prose what George Orwell, James Baldwin, EB White or Samuel Johnson did for English.

His telegraphic prose became proverbial, forever changing how Iranians would read the world. His essays on leading literary figures, such as Nima Yooshij and Sadegh Hedayat, remain among the most insightful works of literary criticism in the language.

Perhaps his most controversial text was an autobiographical confession titled Sangi bar Guri (A Tombstone), in which he wrote candidly and subversively about his inability to have children, his extramarital affair, and his exceedingly loving but troubled relationship with his wife, Simin Daneshvar.

Daneshvar (1921-2012) was a towering literary figure in her own right; her masterpiece novel, Savushun, was a landmark in modern Persian fiction. The couple cut an exceptionally powerful set of public personae and deeply influenced each other’s work. The recent publication of their extensive correspondences has shed light on a crucial aspect of the private and public lives of prominent couples in Iran.

Critical revaluation

Al-e Ahmad died at the age of 45, purportedly from a sudden heart attack, though it has also been claimed that he was poisoned by the agents of Savak, the Shah's secret police.

His wife’s eulogies for her husband today read as landmarks of literary prose, illuminating the deepest aspects of love. They were written with a forgiving soul that turns troubled realities into enduring truths.

Soon after his death, and upon the violent triumphalism of the Islamic Republic that took over after Iran’s 1979 revolution, the legacy of Al-e Ahmad became as divisive as his lifetime achievements. Iran’s ruling elite began actively incorporating his memory into the ideological apparatus of the Islamic Republic, naming highways after him, printing stamps in his honour, and giving literary prizes to commemorate his legacy, while paradoxically, the English translation of his travelogue to Israel turned him into a fully fledged Zionist.

As his detractors began blaming him for the atrocities of the Islamic Republic, the vast and variegated contours of his short but exceptionally fruitful life were lost and neglected in the process.

My renewed interest in Al-e Ahmad, which led to my critical revaluation of his life and legacy, was prompted by a need to retrieve the cosmopolitan disposition of the age that gave birth to his character and the rich body of work he left behind. In doing so, I also paid closer attention to his relationship with Daneshvar, detailing how their respective voices had become dialogical.

My paramount concern was to retrieve a mode of being a Muslim in the world, in which a towering Muslim intellectual was embracing the planet in all its contradictions and paradoxes, rather than dismissing and rejecting them in an act of futile piety or staged resentment.

Good or bad, pleasant or nefarious, critical or implicated, Al-e Ahmad represented a moment in a Muslim’s intellectual engagement with the world when banal sectarian divisions or deeply alienated triumphalism had not distorted the rich and effervescent intellectual legacy of Islam.

It is in that sense that the legacy of Al-e Ahmad as “the last Muslim intellectual” becomes a prelude to a post-Islamist liberation theology, which shimmers in the future of the Muslim world.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.