Iran reframed: Navigating the country's ideological battleground

Power is transitory. In 1818, radical romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley published a compelling sonnet, “Ozymandias”, which reminded readers of the arrogance of great leaders and their mighty decline. Based on Ramses II, one of the most powerful Egyptian pharaohs, it depicts the ephemerality of power, irrespective of the glory, tyranny and cruelty embedded within it.

Narges Bajoghli’s book, Iran Reframed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic, locates Ozymandias in Iran, highlighting the transitory nature of power for all great leaders of the past, present and future. Bajoghli gives a holistic account of the media, culture and military as an ideological battleground in the post-revolutionary Islamic Republic.

Beyond the headlines

Bajoghli, an Iranian American, spent a decade travelling through Iran to explore the notion and operation of power in Tehran. Her book is a product of her extended visits and fieldwork trips, with her intensive research on the country’s politics, society and history describing how Iran’s ideological and security landscape has changed since the 1979 revolution and the ensuing Iran-Iraq War.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Iran Reframed moves beyond the controversial headlines to delve deeply into the country’s complex landscape of culture, identity, survival, religious symbolism, and the struggle to continue the spirit of the revolution among the new generation.

Moving beyond the binaries that exist in Western discourse on Iran, Bajoghli brings to the fore the challenges faced by the Iranian regime - primarily, its credibility crisis and the scepticism of a younger generation. To overcome this existential crisis, the regime and its supporters, including the Revolutionary Guard, have appropriated forms of “banned popular culture”, such as music, to communicate pro-regime messages to young audiences.

This has exposed a generational change in how the revolutionary language upon which the Islamic Republic was built is understood by young people today. To bridge this gap, Bajoghli found, pro-regime media have created cinema on revolutionary subjects and offered opportunities for youths to produce it on their own.

A deep disconnect

In Iran, there exists a deep disconnect between the new generation and those who came before them. The 2009 Green Movement, which demanded the removal of then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, prompted retired Revolutionary Guard Reza Hosseini to note: “They [the young] need to know that we’re not their enemy. But the Green Movement and our response in 2009 made them feel we’re against them.”

This builds to the existential crisis that the theocratic regime faces today; more than half of Iran’s population had not yet been born at the time of the revolution in 1979.

Bajoghli's book is a product of an academic quest, one that is indispensable for understanding Iranian society as it exists today

Spending time with pro-regime film producers in Iran, Bajoghli uncovered the nuances of this cultural battle to keep the revolution alive. She discovered a culture of competition and creativity, with the language of revolution evolving to go beyond the Islamic Republic and to focus, instead, on Iran as a nation - “the thing that we’re all defending, not just a regime or ideology”.

The generational fissure further widens the divide between “insiders” and “outsiders”, with so-called insiders believing in the supreme authority of Iran’s theocratic leadership, and so-called outsiders believing that the regime’s understanding of Islam disadvantages Iranian society.

This politicisation of Shia Islam since 1979 has been manifested in laws demarcating “permissible” dress, and further entrenched in the creation of war culture and memorialisation of the eight-year Iran-Iraq War, a foundational narrative of the Islamic Republic.

Defining the revolutionary narrative

Like the Basij paramilitary force, the Revolutionary Guard have steadily increased their presence in Iran’s socioeconomic sphere, becoming the most “powerful and independent institution within the regime”, Bajoghli writes. Yet, as the regime emboldened both organisations by giving them moral control over Iranian society, signs of internal dissent surfaced, as pro-reformist sentiment gained ground.

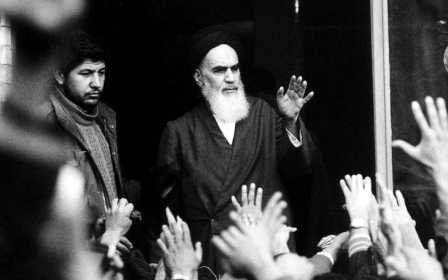

While Ayatollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian Revolution, and his family were seen as reformists, his successor, Ayatollah Khamenei, emerged as a hardliner, focused on securing his position.

What is happening in Iran today is not unusual. Cultural propaganda plays a key role in any nationalistic project anywhere in the world. But in Iran, what is unique is the contestation over the “correct” revolutionary narrative.

The history of the Islamic Republic navigates through complex, often overlapping, internal and external factors. Bajoghli’s book is a product of an academic quest, one that is indispensable for understanding Iranian society as it exists today.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.