Like the toppling of Saddam's statue in Iraq, Putin needs a fake 'victory' in Ukraine

In the centre of Baghdad 19 years ago, a statue of Saddam Hussein was toppled, offering Iraqi and global audiences a symbolic end to his regime.

I witnessed the event on television in my childhood room in California - the same place where, two months earlier, I had received a 6am phone call from CNN. The station was requesting my comments in response to the British government’s plagiarism of my doctoral research for a 2003 dossier arguing for the Iraq invasion.

Both wars offer lessons on the hubris of great powers, the determined resistance of nations under occupation, and the choreographed spectacle of war

Intelligence reports, "shock and awe", and the closing scene of the 2003 Iraq invasion all resonate with the current war in Ukraine. Both wars offer lessons on the hubris of great powers, the determined resistance of nations under occupation, and the choreographed spectacle of war, meant to inspire citizens of the invading country and intimidate the invaded.

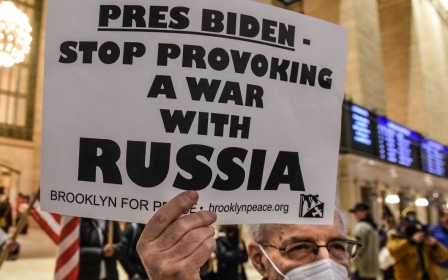

Both American and British declassified reports had warned of an impending Russian invasion of Ukraine, but the manipulated intelligence in the lead-up to the Iraq war resulted in few taking the American warnings seriously nearly two decades later.

In 2003, British dossiers were released to the public as part of the political theatre of the Iraq conflict, managed by both the UK and US to sway global public opinion. American intelligence also warned of the dangers of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, which did not exist.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Last year, the boys who cried wolf released intelligence assessments to warn a skeptical Ukraine and the world of an impending Russian “shock and awe” campaign.

Cinematic wars

The opening salvos of the Iraq war in March 2003 included aerial attacks and volleys of guided missiles. US military war planners had used the phrase “shock and awe” to describe this showcase of American firepower, which they had assumed would intimidate the Iraqis into submission.

While the shock and awe failed to dissuade Iraqis from resisting, the terms suffused everyday parlance, just as Germany’s World War Two blitzkrieg warfare strategy became an American football tactic, and Saddam’s promise of the “mother of all battles” during the 1991 Gulf War has been referenced when describing events such as the “mother of all sales”. In a similar vein, “shock and awe” seems more suited to a department store ad campaign: “Our low prices will shock and awe you.”

Nearly two decades later, these banal terms have again been invested with a fresh lethality. A Foreign Affairs article described Russia’s plan to use overwhelming force against Ukraine as “Russia’s shock and awe.” Geopolitical analyst George Friedman has also pointed to Russia’s attempted “shock and awe” strategy.

Indeed, both the US and Russia deployed shock and awe in an intense, action-packed teaser to their cinematic wars. Afterwards, both would need to stage an event to signal the climax of their campaigns.

The climax

On 9 April 2003, I screamed: “Mom! Come up here, quick,” as I jerked myself into an upright position from bed. “What is it?” she asked seconds later, breathless and leaning on the doorway. “Look,” I said, pointing at the TV screen while scooting myself to the edge of the bed.

My mother said: “I just ran up those stairs thinking something happened to you!” I replied: “Would you just get over here and look at the TV?”

American soldiers were mingling among a crowd of Iraqis in Firdos Square in the middle of Baghdad. The camera slowly panned back, and I saw that the crowd had formed at the base of a statue of Saddam. They were doing something to his statue that I never thought I would see in my lifetime: They were preparing to pull it down.

Shock and disbelief raced through me as I watched Saddam’s metal body topple. I could neither smile nor cry. All I could do was stare at the television screen in front of me. It was as if the entire war had been a movie that had climaxed at this very moment, with the fall of Saddam’s statue. The curtains were about to close on Gulf War II: Operation Iraqi Freedom.

My mother and I continued to watch the TV screen, feeling shock and awe. A phase of our lives had come to an end in my room of our suburban California home.

Illusion of victory

Yet, as it turned out, that entire event had been staged for the media. Weeks later, a wide-angle picture of Firdos Square on that day was released, showing that the area had been practically empty when the statue was toppled.

When I watched the spectacle on TV, I assumed thousands of Iraqis were present. After looking at the event from a wider angle, there could not have been more than a couple of hundred people present - mostly US Marines and international media, along with a handful of Iraqis.

Putin is becoming ever more desperate for a symbolic win to give the cameras closure

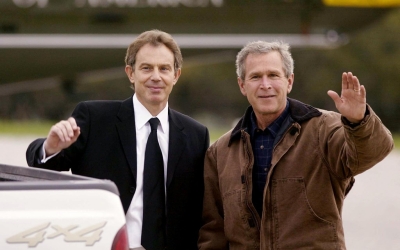

One of the most memorable incidents that I witnessed in my life was a choreographed event to signify an end to the Iraq invasion, so that US President George W Bush could declare victory, albeit prematurely, given the impending insurgency.

Unlike in 2003, the fall of Ukraine’s capital has proven elusive for Russian President Vladimir Putin. As Russia withdraws from Kyiv’s outskirts, Putin will seek to stage another event that will give the illusion of the war ending with a victory for Moscow.

Yet, despite the theatrics, shock and awe ended up killing countless Iraqis and Ukrainians. Unfortunately, Putin is becoming ever more desperate for a symbolic win to give the cameras closure, aiming to spin a “victory” for Russia’s domestic audience to shore up his regime - at the cost of thousands of lives.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.